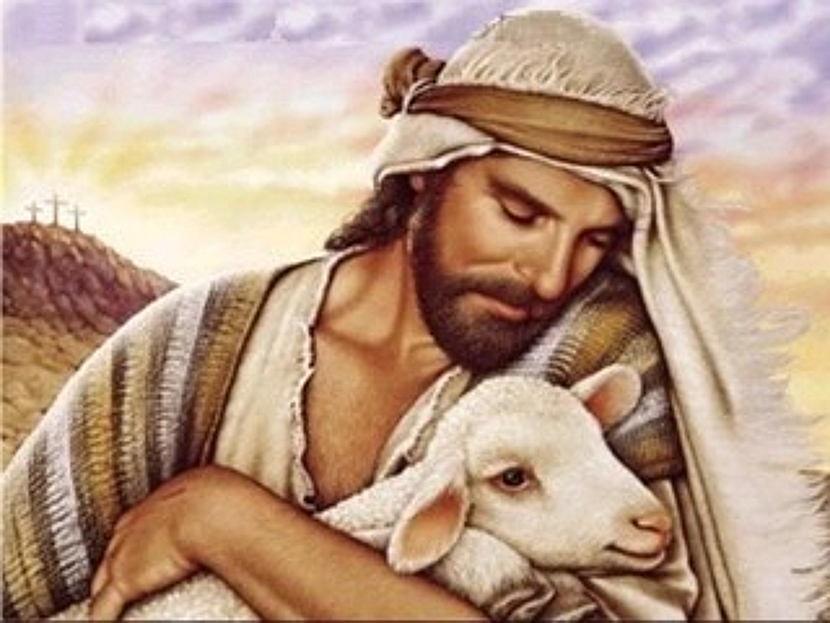

Jesus said, “I am the good shepherd. A good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep. A hired man, who is not a shepherd and whose sheep are not his own, sees a wolf coming and leaves the sheep and runs away, and the wolf catches and scatters them. This is because he works for pay and has no concern for the sheep.” (John 10.11-13)

In reading Frank McCourt’s memoir, Angela’s Ashes, it doesn’t take long to discover that other people’s indifference to the poor is one of his central themes. With an alcoholic father and a mother desperate to feed her children, McCourt provides a picture on every other page, if not every other paragraph, of the indifference that his family faces as they try to find food, clothes, and shelter. His world, as he describes it, is a heartless place.

Towards the end of the book, Frank recalls the time that his mother was four weeks behind on the rent and was using the wallpaper and boards in a wall to make a fire in the apartment so that they could have fuel for the stove. He writes, “Mam . . . sits by the fire wondering where in God’s name she’ll get the money for a week’s rent never mind the arrears.”

“She’d love a cup of tea but there’s no way of boiling the water till Malachy pulls a loose board off the wall between the two upstairs rooms. Mam says, Well, ‘tis off now and we might as well chop it up for the fire. We boil the water and use the rest of the wood for the morning tea but what about night and tomorrow and ever after?”

“Mam says, One more board from that wall, one more and not another one. She says that for two weeks till there’s nothing left but the beam frame. She warns us we are not to touch the beams for they hold up the ceiling and the house itself. . . She goes to see Grandma and it’s so cold in the house I take the hatchet to one of the beams . . . I pull on the beam, the ceiling groans and down on Mam’s bed there’s a shower of plaster, slates, rain.”

When the rent man appears and sees that the wall has disappeared, he erupts, “Dear God in heaven,” he says, “this takes the bloody biscuit, this is goin’ beyond the beyonds. No rent and what am I to tell Sir Vincent below in the office? Out, missus, I’m puttin’ ye out. One week from today I’ll knock on this door and I want to find nobody at home, everybody out never to return.”

Having already worked our way through much of the book, we recognize the rent man as a familiar face, one that has appeared regularly as the destitute McCourt family seeks out help from others, whether at the public welfare office or the St. Vincent de Paul group or the local church. At each place, the face of indifference appears, a face that shows little to no compassion, no concern, no care for Frank’s family.

McCourt’s book is a good primer for what Rabbi Jesus described when he spoke to his followers of the hired hand who cares nothing for the sheep under his watch because, as he told them, “he works for pay and has no concern for the sheep.” The word that the Rabbi uses here for no concern is often translated as unconcerned or cares nothing. Each word reflects the same thing–indifference.

In this passage from John’s gospel, often known as the Good Shepherd Discourse, the Teacher offers a contrast between himself, the shepherd who cares, and those who are unconcerned about the sheep, variously portrayed by the Rabbi as thieves, strangers, and hired hands. His point is always the same. While he is willing “to lay down his life for the sheep,” his opposites run for cover at the first hint of a wolf on the prowl. Why? Because they don’t care. They’re indifferent.

By means of this contrast, the Teacher makes clear that his followers, if they want to be like him, can never be unconcerned about the pain of others, uncaring for those who cry out, or indifferent to the suffering of others. Always, the disciple has to be willing to lay down his or her life for others, just as the Teacher has done and will do definitively when he dies on the cross.

While we often tend to see ourselves as the sheep that Rabbi Jesus referred to–and justifiably so–it is also important that we see the sheep as those that the Teacher showed a special concern for during his walk through Galilee, those whom he found on the side of the road left for dead, those whom he heard pleading for mercy, those whom he saw despised and disdained by the powerful and the highly positioned.

As followers of the Galilean, it is our duty to care for these sheep as he did, answering their cries, healing their afflictions, and feeding their bodies and spirits. Hearing him speak to his followers, calling himself the Good Shepherd, we see he makes it clear that any who would follow him must become good shepherds also, caring for the sheep who have no one to care for them.

This becomes the hallmark of those who follow the Good Shepherd–their care and concern and compassion for others. It is the blood that runs through their veins. Or as the old expression goes, “People don’t care how much we know until they know how much we care.” How much we care has always been the defining quality of the Christian believer.

Unfortunately, we live in an age and a time where the opposite is too often seen, where the indifference of the thieves, strangers, and hired hands that the Teacher spoke of seems to win the day, leaving the sheep to scatter and to suffer immeasurable assaults and assailants without any assistance, good shepherds seemingly few and far between.

A man writes of seeing a scene play out recently on a busy street. An elderly man and woman waited at the corner. Both were old, bent over, and unsteady. They walked cautiously to the curb and stepped down together. The man held the woman’s arm as she slowly moved across the street, offering her support and some sureness of step.

Because their steps were slow, the light changed before they made it across. Soon cars were honking, impatient drivers annoyed at the delay of a few seconds, unmoved and unconcerned about the safety of the couple, preoccupied only with their own schedules, prevented from showing any compassion because of their own selfishness. At that moment, they were the thieves that the Rabbi spoke of, insensitive to the situation of the aged couple struggling to make it safely to the other side of the street.

Of course, our age does not own indifference, although it is increasingly comfortable with it. Rabbi Judea Miller once told the story of the body of a young Polish Jew that was found on May 12, 1943 in his London apartment. His name was Samuel Zygelbojm and he was an escapee from the Warsaw Ghetto. He had come to London to tell the world of the Nazi genocide of the Jews.

Begging for quick action, Samuel warned that those Jews who remained in Poland were sure to be exterminated soon. He asked that the rail lines leading into the death camps be bombed so that more prisoners could not be brought in or that the gas chambers be bombed so that they could no longer operate. He pleaded for world leaders to express outrage and to hold accountable Nazi Germany. But his words and experiences had no effect. No one seemed to care.

Desperate, he wrote a letter to the press, expressing urgency, begging for action to stop the genocide. Then he committed suicide, hoping his death might shock the free world out of its inaction and indifference. The New York Times printed his letter on the back page and his death largely went unnoticed, with over six million lives lost as a result of the unconcern.

Let there be no mistaking or misunderstanding the seriousness of indifference. It is an evil because lives are at stake because of it. So long as people are indifferent, the poor remain poor, the hungry remain hungry, and the naked shiver in the cold night air. And if we do not take the part of the Good Shepherd, then we are condemned to take the part of the thieves.

Some years ago, the journalist Mike McIntyre decided to leave his job and hit the road, planning to walk from one end of the country to the other with nothing but the clothes on his back and without a single penny in his pocket. He wanted to determine how many people out there would end up being a good shepherd to him and how many would be thieves. As we might expect, it was a mixed bag, as he tells us in his book, The Kindness of Strangers, in which he recounts his long journey.

However, at one point he tells of asking a pastor if he could sleep in the church overnight. The pastor tells him that he can’t let people sleep inside, but he offered McIntyre a motel room. McIntyre responded that he’d rather the pastor save the funds for the truly needy. Then the pastor said he would call a family who was willing to take people in.

Watching the pastor make the call, McIntyre heard the man on the other end of the phone say, “Send him over.” Since McIntyre had no means of getting there, the pastor suggested to the man that he come get him. Hanging up the phone, the pastor explained that Tim “was a little rough but a good man. He’s fallen for the Lord hard,” explained the pastor.

Soon, Tim showed up, living around the corner from the church in a duplex. He explained to McIntyre that he and his wife kept one unit open for people who needed emergency shelter. Tim called it his ministry. As he explained to McIntyre, “Just showing up at church on Sunday and putting a few shekels in the plate isn’t enough. If you’re gonna be a Christian, be a Christian.”

The next morning, McIntyre learned that Tim wasn’t through giving. He wanted him to take his tent, the one he slept in when he worked in the desert. Refusing the offer, McIntyre saw that Tim wasn’t going to take no for an answer, his host explaining that “it just sits in the garage.” Finally, McIntyre agreed, knowing it was probably one of Tim’s more valuable possessions.

Tim, we could say, was the good shepherd that Rabbi Jesus spoke of when he told his disciples that they had a choice to make–become good shepherds or be thieves. Tim showed concern and care for the less fortunate, always the truest sign of the good shepherd. Thieves, on the other hand, show indifference, which is about as far away from a follower of Jesus as a person can get.

–Jeremy Myers