Brothers and sisters: I received from the Lord what I also handed on to you, that the Lord Jesus, on the night he was handed over, took bread, and, after he had given thanks, broke it and said, “This is my body that is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” (1 Cor 11.23-25)

When the writer-philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff lost his 25-year-old son Eric in a mountain-climbing accident, he poured his grief into a small book that later carried the title, Lament for a Son. Since its publication in 1987, Lament for a Son has spoken as few books can to the grief of separation that comes when death strikes. It is read with tear-filled eyes.

Two years ago, when Wolterstorff published his memoirs, which he entitled In This World of Wonders, he spoke again of Eric, the son he had lost. He revisited those moments after he had returned home to his waiting family, having identified his son’s body in Germany and having flown back to the United States, trying to find words to say.

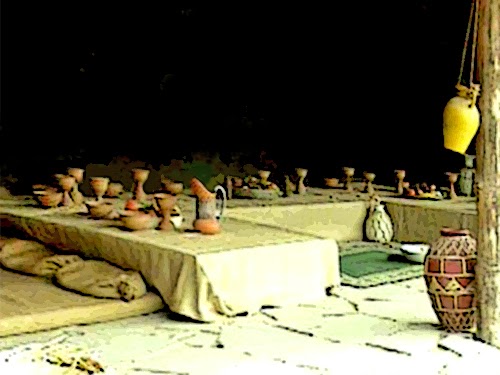

He writes, “It was late when I returned home, but I assembled the family. I remember only what I said first and last. ‘Our Eric is gone,’ I said. And, at the end, I said that we had to remember him, not put him out of mind, not forget him. And that’s what we have done: remembered him. Photos of him are on display, and ceramics that he made when he was in high school. We talk about him, more at first than now, naturally, but his name still comes up rather often, along with memories.”

Later, he writes, “I would own my grief. When tears came, I would let them flow. When telling about significant events in my life, I would tell about my love for Eric, and about his death, and about my grief over his death. I would preserve the memories, and I would live with the disturbances and disruptions in my life that those memories created.”

He explains to the reader, “Setting out some of the truly beautiful ceramic pieces that Eric created when he was in high school, where we see them daily, is a way of keeping alive our memory of him and a way of honoring him. They are memorials, as are the photographs we keep out. Anything in my experience, no matter how innocuous–a chance remark, a piece of clothing, a work of art–bears the potential of triggering a chain of associations that culminate in renewed grief.”

Reading these deeply personal words, we feel deep in our bones the sense of loss that stays with this grieving father who says that time now is divided into before Eric died and after Eric died. And it is painfully clear that he wants to remember his son, his adventurous child, and he intentionally keeps physical mementos in his home, objects that recall the one he loved and lost.

That feeling of love and longing that Wolterstorff so beautifully shares with us is what we want to bring to this particular day when the scriptures also share a story of a young man whose life was taken too soon, and of the friends who grieve the loss of the one who sat at table with them innumerable times, breaking bread, sharing a cup of wine, cementing a bond of community.

Particularly poignant in the story that the apostle Paul shares with us are the words that the young man known to us as Jesus of Nazareth spoke to his friends as they sat for one last meal together in the upper room, his executioners putting together the evil plot a few blocks away that will end with his brutal assassination. He says to them, “Remember me.”

Somehow, those two simple words sum up the deep desire that we humans have to be remembered after we are gone, the hope that someone will think our lives were important enough to hold onto, the want that those we loved will love us enough to remember us when we are no longer physically with them. “Remember me,” he said to them, the words spoken with pain and with petition.

Perhaps knowing well our propensity to push painful things in our past into cardboard boxes in the attic, he provides a simple but powerful way for them to remember him, inviting them to look less at his absence, and more at his presence, found now in a meal as they sit at table, his place with them promised as they eat and drink if they recall his words and his way in the world.

“For as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup,” he said, “you proclaim the death of the Lord until he comes,” asking them to find in this everyday event a way to keep him in their minds, in their hearts, and in their spirits. As they had done innumerable times before, enjoying each other’s company over a table of food and drink, so now, he asks, they continue to congregate, using the occasion not only to nourish their bodies, but to nourish their spirits, as they remember him.

A woman remembers how she would call her friend every day when the numbers of the clock were all the same. It was a practice they had started years earlier, one or the other making the call when the clock read 11:11 or 3:33 or 5:55. In fact, that is the way they greeted one another over the telephone, “It’s 10:10” or “It’s 2:22.”

Now that her friend is gone, the woman often looks at the clock. Even her children take notice of it when the numbers align. They all shout out, “Hi, Aunt Bessie!” Together, they talk about her for a minute or so, remembering her in this simple, but real way, the woman they loved and who loved them, numbers on a clock serving as a means to stay connected, even if she has ceased to be, at least on this side of the great divide.

The Galilean called Jesus used the meal as the means to remember him, not only so his followers would stay connected with him, but also so his followers would stay connected with others, because it was what he did, inviting one and all to sit down at table with him, the uninvited as well as the invited, the unwelcomed as well as the welcomed, the unwanted as well as the wanted.

This was the one constant in his meals–anybody and everybody could find a place at his table–a practice that won him the favor of misfits and misfortunates, but earned him the disfavor of the posh and the powerful. “He eats with sinners” was the most common commentary spoken about him, usually with a big dose of shock and surliness in the voices of his critics. Simply stated, he was upturning the tables, upsetting the status quo, upending the way things were done by his blindness to who’s good company and who’s bad company, who’s in and who’s out, who’s our people and who’s not.

So, if we are to be faithful to him and his meal fellowship, then we can’t be content with simply coming together to enjoy a brewski while we reminisce about what a character he was. We need to be sure we are taking care, not so much of ourselves, but of the same ones he took care of, turning his memory into a lived experience, rather than a trip down memory lane.

A few years ago, a woman spoke of how she found just such a lived experience when a former church was turned into a food pantry. Volunteers removed the pews and replaced them with shelves that held groceries. The choir loft held a bunch of baby diapers, while toothbrushes and toothpaste were kept in the sacristy.

She spoke lovingly of the connections that are made at the food pantry, not only among the workers, but among the guests who come there twice a month to find rice and beans, veggies and fruit, milk and meat. No one is turned away. As she so beautifully said, “Until I can get to the point where I see no distinction between a guest at the food pantry and myself, I am still in need of transformation.”

What she has found at this church-turned-food-pantry is a way to be Eucharist for others. She writes, “We gather as the people of God and offer all that we are with each bag of groceries. We struggle to become united as sisters and brothers in one human family. We strive to be inclusive, revolutionary in our sharing and authentic. She sums it up in this way, “In the forming of community, where once the Blessed Sacrament was adored, we become Christ’s body and blood for all.”

There is something so obviously right about what is going on in that place, where volunteers such as herself not only gather to remember the life and the ways of the Galilean Teacher, but also become his living presence to others, feeding them as he fed the hungry, accepting them as he accepted the unacceptable, loving them as he loved even the unlovable.

Years ago, the 5th century theologian Augustine told his churchgoers, “Become who you receive,” making it clear to them that remembering the Lord Jesus by coming to his table is not enough. They also must become nourishment for others as he has become food for them. We must do as he did. Then he is truly remembered in the way he wanted when he said, “Do this in remembrance of me.”

In Frank McCourt’s book ‘Tis he tells of one of his first jobs teaching English at a high school on Staten Island. The students are loud and rude, hitting each other with chalk, erasers, and food. They have little, if any, interest in learning, showing no respect to their teachers.

One day, while the class is taking a test, McCourt takes a look into the closets at the back of the classroom. He finds old newspapers, books, and hundreds of uncorrected student compositions going back to 1942. Standing there, he begins to read through some of the compositions, hearing some of the boys write about their desire to join the fight, to avenge the deaths of brothers or neighbors already killed in the war. Some of the girls write about their waiting for boyfriends to return from the war, their hope to get married, their want for a new life in New Jersey.

On a lark, McCourt began to read some of these essays to his class. He found that they sat up, giving attention to his reading. When they heard familiar names in the essays, they said out loud, “Hey, that was my dad. He was hurt in Africa.” Or, “Hey, that was my Uncle Sal who got killed in Guam.”

As McCourt continues the project, the class hears of dozens of Staten Island and Brooklyn families named in these handwritten papers, pages so brittle they almost crumble in McCourt’s hands. The students want to save them so they begin to copy them.

For the rest of the term they read through the essays, tears flowing as the students read about their mothers and fathers, aunts and uncles. “This is my dad when he was 15,” one of them says. Or, “This is my aunt and she died having a baby.”

What his class saw in that stack of crumbling, long forgotten, almost lost student compositions was people from their past who were brought back to life through their rediscovered essays. Suddenly, in this heap of yellowed and brittle pages the students found a way to remember people from their past, people who lived and loved as they did, people who deserved to be remembered.

Today, we read about a man who also had dreams, who wanted a better world, who liked to sit down at table with just about anybody, sharing not only a meal with them, but sharing humanity with them, in this way letting them know they were somebodies, at least to him, even if they were nobodies to just about everybody else.

As we hear his story told again, we hear him ask us to remember him, not only in retelling his story, but in reliving his life as he lived it. Then, he is not only remembered, he is alive again.

–Jeremy Myers