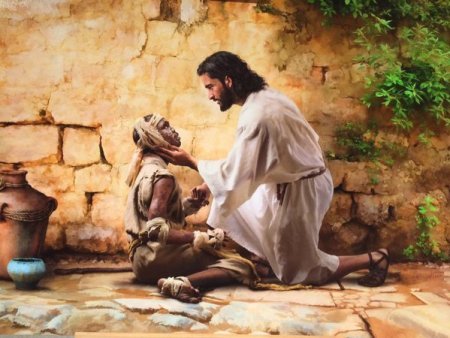

A leper came to Jesus, and kneeling down, begged him and said, “If you wish, you can make me clean.” Moved with pity, he stretched out his hand, touched him, and said to him, “I do will it. Be made clean.” The leprosy left him immediately, and he was made clean. (Mark 1.40-42)

In Graham Greene’s book, A Burnt-out Case, he tells the story of a famous architect named Querry who has lost all joy in living. He flees the world he knows for the Congo, where he works in a leper colony run by Catholic missionaries. In working with the lepers, his burnt-out soul slowly rediscovers meaning and community.

At one point in the book, Greene tells of Doctor Colin who is the resident doctor for the leper colony and who diagnoses Querry as a “burnt-out case,” writing of the doctor in this way, “Patient after patient exposed his body to him; in all the years he had never become quite accustomed to the sweet gangrenous smell of certain leprous skins, and it had become to him the smell of Africa.”

Continuing the scene, Greene writes, “He ran his fingers over the diseased surface and made his notes almost mechanically. The notes had small value, but his fingers, he knew, gave the patients comfort: they realized that they were not untouchable. Now that a cure had been found for the physical disease, he had always to remember that leprosy remained a psychological problem.”

As the story progresses, the reader sees soon enough that nearly everyone in the book is a burnt-out case, each person struggling with the search for meaning and with the want for a genuine connection with another person who could reach out and touch, if not their frail bodies, then their broken spirits.

That story and its message serves as a good backdrop for the gospel narrative that Mark the evangelist presents to the reader today in his own story about a leper. This leper, breaking the prohibition against coming close to another person, lest his contact result in passing on the contagious disease, approaches Rabbi Jesus, kneels before him, and begs for a cure. “If you wish,” he says to the Galilean, “you can make me clean.”

With that opening sentence, the evangelist presents us, not only with the case of the leper, but with the case of burnt-out humanity at large, where we all yearn to be made well again, not so much from leprosy, but from the disease of disconnection, a lack of genuine connectedness with others, causing each of us to feel untouchable, if not physically, then psychologically.

As we gain a greater understanding of leprosy in the ancient world, we learn that those persons afflicted with the disease were forced to live outside the camp, the physical space from others providing some assurance that their disease would not be communicable to others. With that separation from others, further accentuated by being required to wear a bell on their foot to alert the passerby, the leper was truly an outcast, separated in every way from the human community.

It comes as no surprise, really, that the Galilean Teacher showed none of the fear that others had of a leper, his purpose always more concerned with bringing good news to the least, the last, the lost, and the lonely, this leper the epitome of just such persons in a society determined to push away and to put at arm’s length those labeled as “other.” Breaking societal restrictions, Rabbi Jesus stretched out his hand and touched him, that singular action an indication that he would not follow the way of a world that turned a blind eye to those in need.

Not to be minimized, the action of stretching out his hand, also understood as extending or embracing, becomes the quintessential symbol of the Galilean’s mission, to bring close those who were far, to reunite those who were separated, to see those who were unseen. As he travels through Galilee, the Rabbi will continue to stretch out his hand to the diseased, the distressed, and the disaffected.

And, in reaching out to them, moved always by compassion, meaning their suffering brought him suffering, he healed them of whatever was stealing their life from them, whether physical sickness, psychological demons, or spiritual emptiness. With his restoring life to all those who suffered, he brought them from outside the camp and back into the camp of humanity.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, the Swiss physician Paul Tournier became well-known for his personal skills in healing sick patients and for his writing on patient care. Doctors from around the world traveled to his home in Switzerland to learn from him. Tournier once commented on his popularity, admitting, “It is a little embarrassing for students to come over and study my ‘techniques,’ adding, “They always go away disappointed because all I do is accept people.”

All I do is accept people. Dr. Tournier, in his simple ability to accept people, to stretch out his hand to them, found the key to healing those tormented by physical, psychological, or spiritual infirmities, touching them in the core of their humanity, where they desired to be one again with the community, not separated from contact with a caring person, which is so vital to the well-being of each and every human person.

If the gospel passage is to speak to us and if we are to be healed of the leprosy of feeling disconnected, the feeling of living outside the camp that afflicts our humanity in these times, then it will be necessary for us to rediscover again that ability to reach out to others, to accept others, and to touch their spirits with kindness, with generosity, with compassion.

It is not without significance that the contemporary writer Noreena Hertz has called the twenty-first century the loneliest century we have known. In her book called The Lonely Century, she speaks of the plague of loneliness that has ravaged the globe, evidenced by the staggering human toll that results from the disconnection that so many people feel in their lives today.

She tells of learning about a company called “RentAFriend,” founded by a New Jersey entrepreneur, who now has footholds in dozens of countries around the world with over 600,000 employees. For forty dollars an hour, anyone can rent a friend for the afternoon. If you don’t want to show up at a party alone, or if you’ve moved and don’t know anyone in town, or if you want company at dinner, then you can rent a friend.

Offering still another shocking example, she tells of older people in Japan who commit petty crimes so that they can be sent to prison, preferring the jail cell to their four walls at home because it provides them with human contact and with a daily connection to others, something they don’t have in their own homes.

Analyzing the rampant loneliness of the present age, Hertz offers statistics that stress the health risks that ensue from this sense of “living outside the city.” She writes that loneliness is worse for our health than not exercising, as harmful as being an alcoholic, and is equivalent to smoking fifteen cigarettes a day.

She suggests that the culprits or catalysts for this loneliness are no strangers to us, including smartphones and social media, which–ironically–are pushed as means to connect us to others, but–in fact–separate us from others. Our work environments also do not lend themselves to being gathering places and our competitive society blinds us to the cooperation needed to have a human community. The simplest explanation, she points out, is that we don’t do stuff together anymore, or, as she says, our world is pulling us apart.

The solution is within our reach. She writes, “We need to rush less and stop and talk more, whether it is to the neighbor we often pass but never speak to, a stranger who has lost their way, or someone who is visibly feeling lonely, even when we’re feeling overloaded and busy.”

Listening to those recommendations, we realize that the remedy is as old as the teachings of the Galilean Rabbi, who taught us that we have to care for one another, reach out to others, and actually see those who, through no fault of their own, are overlooked. We have to make space in our lives for one another, as he did for the leper who suddenly stood before him.

A few years ago, a man wrote of a difficult period in his life when he suddenly found himself all alone. Later, after the crisis had passed and he was back on his feet, he spoke publicly at a meeting of his colleagues where he described to them what he called “the silence at the center of the noise,” referring to the phone that never rang, the feeling of being deserted by them.

“Where were you?” he asked the group. Explaining that while he didn’t expect them to fight his battles, he did expect their friendship, an offer of prayers, or a shared cup of coffee. He said to them, “We could have talked about something else. Or we could have just sat together for a bit, not saying anything. Where were you?”

That is the question that we all ask ourselves today, as we reflect on the life of Rabbi Jesus, who was always there for the person having a bad day, or a bad time, or a bad life. He opened up a space for them in his life, reaching out to them, assuring them that he saw them and he was there for them in their struggles, whatever they were.

As the evangelist tells us today, he stretched out his hand, touched the leper, and said to him, “Be made clean.” And he was. If we are to stand a chance of becoming anything close to who he was–that is, love incarnate–then it begins with stretching out our hand to others, seeing in them, not some stranger, but someone just like us. In that simple gesture–of reaching out to others–we bring them from outside the camp back into the human community, where, in the end, we heal one another by being there for each other.

–Jeremy Myers