Then they came to Capernaum, and on the Sabbath Jesus entered the synagogue and taught. The people were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority and not as the scribes. (Mark 1.21-22)

By now most everyone has heard or has read Mitch Albom’s book, Tuesdays with Morrie, his moving memoir of the months he spent with his old sociology professor, Morrie Schwartz, who was dying of ALS. Reconnecting after years, Albom had the opportunity to visit Morrie each Tuesday morning for, what Albom called, his professor’s last class, one in which he taught Albom the meaning of life from his deathbed.

At one point in the book, he asked Morrie if he had any regrets in life. Morrie answers, “It’s what everyone worries about, isn’t it?” Then Morrie offers these wise words to Albom, “Mitch, the culture doesn’t encourage you to think about such things until you’re about to die. We’re so wrapped up with egotistical things, career, family, having enough money, meeting the mortgage, getting a new car, fixing the radiator when it breaks–we’re involved in trillions of little acts just to keep going.”

He continues, “So we don’t get into the habit of standing back and looking at our lives and saying, Is this all? Is this all I want? Is something missing?” He paused. “You need someone to probe you in that direction. It won’t just happen automatically.” Albom writes, “I knew what he was saying. We all need teachers in our lives. And mine was sitting in front of me.”

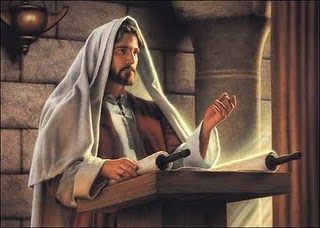

Rabbi Jesus was just such a teacher, someone who guided others, who offered a direction, who showed the way to a life that matters. At the start of the Gospel of Mark, the evangelist identifies him as a teacher. As we heard in the passage for today’s reflection, Jesus entered the synagogue to teach. And, as Mark makes clear, the people who heard him were amazed at his teaching.

His entering the synagogue to teach was not a one-time incident. As the gospel continues, we often find Jesus going into synagogues, the place where Jews gathered to hear teachers offer lessons and interpretations about the Hebrew scriptures. Among the titles that people give to this son of the carpenter is Rabbi, commonly translated as Teacher. Teaching was, for all intents and purposes, his primary task.

Having the benefit of his teachings, we understand what and why and how he taught, his lessons always directing people on how to live, proposing a way of living that brings fulfillment and purpose to each life, done through making the lives of others better and richer. His syllabus was a series of simple truths that offered his disciples the right way to live: Love one another, forgive seventy times seven, feed the hungry, give your coat to the person without one, walk the extra mile, judge no one, welcome the foreigner, embrace the lonely, find the lost.

And should the follower live in this way, he promised a special relationship with the Creator of the world, a connection with the source of all life, an understanding of the heartbeat of God because, in the end, this was the way that the Most High desired and designed the world to be–a place of peace, a place of unity, a place of love.

We’re told that the listeners of Rabbi Jesus found his teaching to be different from the teaching of the scribes and rabbis with which they were familiar, stating his teaching had authority, understood as force, competency, or mastery. As a result, they were astonished, or filled with a feeling of amazement. Clearly, they recognized there was something very different about this teacher.

That contrast will continue throughout this gospel, as Rabbi Jesus shows his authority, while the other teachers, such as the scribes and Pharisees, will show their weakness, particularly through their lack of understanding of Jesus and their failure to practice what they teach. Rabbi Jesus, on the other hand, is recognized even by the demons as “the holy one of God.”

It is not by chance that the teaching in the synagogue is followed immediately by the curing of the man with an unclean spirit, the juxtaposition intentional, providing us with Rabbi Jesus’ authority, now in action, not just in word. “Have you come to destroy us?” the unclean spirit shrieks at Jesus, recognizing immediately the power that this Teacher has.

And, as we see, Rabbi Jesus issues a command to the unclean spirit, telling it to be quiet and to come out of the man, which it does, since it has no power over this Teacher as it does over the man it has possessed. Convulsing the man and crying aloud, the unclean spirit exits the man, leaving the crowd of onlookers in the synagogue amazed for a second time.

In Jewish law, no one was more important than a teacher. The law stipulated that they were to be treated with respect and provided for their services. The reason was simple. A teacher, as Judaism came to see, had the unique capacity to change the world, their teaching influencing the minds and hearts of others to choose one path over another, in this way, turning the world into a different place.

A few years ago, a Jesuit priest writing in a national magazine reflected on one such teacher he had when he was a young boy in the local parish school. Her name was Sister Thaddeus and the lessons she taught were compassion, kindness, and understanding. Remembering her classroom, the writer reflected on memories he had of this astonishing teacher. He wrote:

“My friend Vince had the worst handwriting in the class. Rather than upbraiding him, as other teachers had done, Sister Thaddeus would cheerfully tutor him during recess. ‘It’s getting better, you know. Keep up the good fight,’ she would say to him.”

Or again, “The poorest pupil in class was Charlotte. She also stuttered badly. In Sister Thaddeus’s class, one of the girls would call out a pupil’s name from a stack of cards as we plowed through the daily oral drills. After several weeks, however, I noticed that Charlotte was the one pupil whose name was never called. Only years later did I surmise that SIster Thaddeus had pulled her card to avoid any humiliation.”

He writes, “When our family showed up at the parish socials, we often brought our sister Nancy, who had Down syndrome. Sister Thaddeus would always go out of her way to give a small gift to Nancy: a St. Bernadette medal, holy cards of our Lady, a plastic rosary bracelet.” Seeing there was something very different in the way Sister Thaddeus taught, he could only conclude, as he said, “Whereas many teachers play for the stars, Sister Thaddeus cared for the vulnerable. Her pedagogical compass was compassion.”

We will see, as we advance through this gospel, that the same and more would be said of Rabbi Jesus, whose pedagogical compass clearly was compassion. And it was compassion that he wanted his followers to learn from him as he banished unclean spirits, bound up the wounds of the sick, and brought solace to the brokenhearted.

His teaching was never words alone, but always was words in action, marking him as someone with authenticity, someone with integrity, someone with honesty. His ability to astonish the people continued because he stayed true to himself and to his mission, which was to bring good news into the world, a place very much in need of it.

While Rabbi Jesus held the title of rabbi or teacher, in the end, we who follow him also become teachers, simply by the claim that we have sat at his feet and we have learned from him. And as his followers, we have the duty to pass on his teaching to others, as he has passed them on to us, so that others in the world might come to see the right way to live in the world and the best path to purpose in life.

Years ago, a brilliant violinist who had performed on the international stage became a professor of music at UCLA. Asked why he gave up the glamor and acclaim of the stage for the classroom, the maestro answered, “Playing the violin is a perishable art. It must be passed on, otherwise it is lost.” Remembering something his own teacher had told him, he repeated them, “He said if I worked hard enough, someday I might be good enough to teach.”

There is much for us to learn from the maestro because, just as playing the violin is a perishable art, so is the way of the Teacher of Galilee, his words and his deeds fading into the past unless his students continue to teach others in the world the lessons that he taught, offering the world the same redemption that the Galilean Rabbi offered.

And, as the maestro also said, for those who teach, they must first practice, doing the work before speaking the words, day after day living as Rabbi Jesus lived, so that in time words are not needed for the lesson to be learned by others, our example enough to show them the way of the Teacher. Without that practice, however, our teaching will be no better than the teaching of the scribes, whose lack of putting their words into practice left the people unimpressed and far from astonished.

If we want to astonish people, as the Rabbi of Galilee did, then we must do as he did, his authority coming from his compassion for one and all. In our effort to become that same kind of teacher, we can learn from the story of another teacher, this one named Miss Thompson. She taught fourth grade and in her class she had a student named Teddy Stallard. He was a slow, often unkempt student, a loner shunned by his classmates.

The previous year Teddy had lost his mother and, with that loss, he lost his motivation in school. Miss Thompson found herself not particularly liking Teddy either. Then Christmas came and Teddy brought her a small present. While the other students had well-wrapped presents, Teddy’s was in a brown sack. When she opened it there was a rhinestone bracelet with half the stones missing and a bottle of inexpensive perfume.

When the students began to snicker, Miss Thompson quickly splashed on some of the perfume and put on the bracelet, allowing Teddy to think he had given her something special. At the end of the day Teddy worked up enough courage to softly say to her, “Miss Thompson you smell just like my mother and her bracelet looks real pretty on you too. I’m glad you like my presents.”

As Teddy left the classroom, Miss Thompson broke down and prayed to God to forgive her. She asked him to help her, not only to teach these children, but to love them. She resolved she would become a new person, a better teacher. By the end of the year, Teddy had caught up with the rest of the students because of her.

Miss Thompson didn’t hear from Teddy for a long time. Then she received this note, “Dear Miss Thompson, I wanted you to be the first to know. I will be graduating second in my class. Love, Teddy Stallard.” Four years later, she got another note, “Dear Miss Thompson, They just told me I will be graduating first in my class. I wanted you to be the first to know. The university has not been easy, but I liked it. Love, Teddy Stallard.”

Four years later, another note came, “Dear Miss Thompson, As of today, I am Theodore Stallard, M.D. How about that? I wanted you to be the first to know. I am getting married next month. I want you to come and sit where my mother would sit if she were alive. You are the only family I have now. Dad died last year. Love, Teddy Stallard.” Miss Thompson went to the wedding and she sat where Teddy’s mother would have sat.

She was, we could say, a teacher who learned to teach in the same way as the Rabbi of Galilee taught–with love.

–Jeremy Myers