“As he passed by the Sea of Galilee, he saw Simon and his brother Andrew casting their nets into the sea; they were fishermen. Jesus said to them, ‘Come after me, and I will make you fishers of men.’ Then they abandoned their nets and followed him.” (Mark 1.16-18)

Known for the many works of fiction he wrote, chief among them The Chronicles of Narnia, the 20th century British writer C.S. Lewis also wrote well-known works of non-fiction, chief among them Mere Christianity. Based on a series of radio talks he gave during the dark days of World War II, Mere Christianity served as an introduction to Christianity, Lewis’ work still read widely eighty years later.

At one point in the book, wanting to explain his own decision to become a Christian, Lewis wrote, “Every time you make a choice, you are turning the central part of you, the part that chooses, into something a little different than it was before . . . all your life long you are slowly turning this central thing into a creature that is in harmony with God . . . or else into one that is in a state of war.”

Allowing the words to simmer in our souls, we find in them something simultaneously simple and sublime, condensing the whole of our life into a choice–to be with God or to be against God, a choice that we make a hundred times a day, until, over time, they define who we are in our core, what our character is.

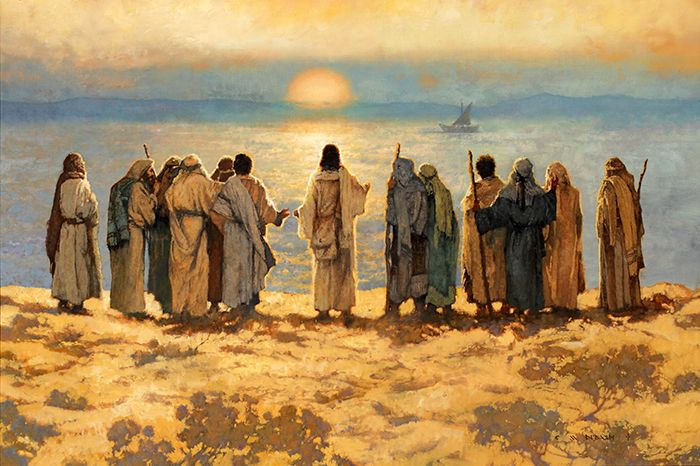

At the start of Mark’s gospel, a part of which we hear today, he tells of the call of the first disciples, fishermen who, on an otherwise ordinary day, came face to face with a not-everyday choice, to stay with their nets or to stay with the traveling teacher of Galilee. Spotting the fishermen as they threw their nets into the Sea of Galilee, the Teacher offered an invitation to them, “Come after me, and I will make you fishers of men.”

In that moment, they had a decision to make, a decision that would decide, not only how the rest of the day went, but how the rest of their lives went. And in the next moment, their decision would be clear–they would continue to throw their nets into the sea, or they would drop their nets to the ground. Mark describes that moment of decision without fanfare, writing, “Then they abandoned their nets and followed him.”

Something very special is presented to us in that sentence, when the moment of decision is rendered, we find the fishermen deciding to change the course of their lives, the first example in the gospel of somebody who heeds the the central message of the Galilean Rabbi, encapsulated in the one word he speaks first, “Repent.”

While we typically like to think of repentance as a feeling of guilt, its original intent is different. Rooted in the Greek word metanoia, repent, as the Galilean Rabbi intends it, means to change one’s mind or to change the direction someone is taking. In its essence, repent means to see things from a different perspective, ultimately to change the course of our physical steps as well as our spiritual stance.

And that is what the fishermen on the Sea of Galilee did in that moment of choice, when the sound of their fishing seines hitting the sands on the shore split the silence, a symbolic split as sacred and as scary as the divide that now would be in their days, their past as fishermen on the seas separated in time and space from their future as fishers of men.

With that radical redirection of their lives encapsulated in that decision, they chose to commit themselves to the good news, euangelion, becoming proclaimers of good news, town criers, not of all that is wrong with the world, but angelic-like voices commissioned to reawaken all that is good in the souls of humanity.

In choosing to follow the Teacher of Galilee, these fishers of men, their old selves abandoned, their new selves discovered, commit themselves to becoming that creature, as C.S.Lewis said, that is in harmony with God, not that creature that is at war with God. From that moment forward, they would walk the path of the Teacher, learning from him what it means to recreate the world in the way that God wants the world to be.

That world, as the Teacher soon shows them, is a world where the lives of the poor are enriched, where the cries of the anguished are answered, and where the hurts of the alienated are healed. It is a world where the choice for good always outweighs the choice for evil, the decision to love is greater than the decision to hate, and the want for harmony surpasses the want for disharmony. In a word, it is a world of good news.

Augustine of Hippo, living in a time as tumultuous and terrible as any, challenged his listeners to drop their nets, leaving behind the ways of this world, and choosing those things that would return the world to its rightful place as a paradise for all of creation, as it was created to be. Aware that too many still chose to hold their nets tightly in their hands, he rightly pointed out, “In order to discover the character of people we have only to observe what they love.”

His words, these many centuries later, have lost none of their importance, none of their urgency, beseeching us to observe what it is that we love, and in discovering what it is that we love, coming to see our true character, whether it is for good or for ill, an accumulation of daily decisions molding us into a person at peace with God or a person at war with God.

The respected preacher, George Buttrick, pastor of the Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church in New York, once repeated a story that he had read in a local newspaper. As the article explained, two workers were walking down a staircase in a factory one day. As they walked by a bucket that one of the men assumed was filled with water, he tossed his cigarette butt into the container.

However, it contained gasoline, not water. Suddenly the bucket burst into flames, engulfing the wall of the stairwell. One of the young men ran down the steps and out of the building to save his own life. The other chose an opposite path. He darted up the stairs to warn others to get out of the building as soon as they could.

Buttrick, in telling the story, said that every person has the same choice to make–to be an upstairs person or to be a downstairs person, to be someone whose first thought is for other people’s well-being, or to be somebody whose every thought is for his or her own survival. When the choice is put to us, will we give up the security of our nets, or will we clutch our nets tightly in our hands, unwilling to let go of our security blanket? Upstairs or downstairs–which direction are we going to take?

When the Teacher of Galilee stood before the fishermen of Galilee, he invited them to run upstairs, not downstairs, asked them to choose a way of life that put others first, not self, and challenged them to reach out to others, not to push them away. When he said to follow him, he was putting before them a path that promised good news to the world, not the path that assured only more bad news in the world.

Of course, it is not enough for us to consider the lives of those fishermen and their choices. It is far more important that we realize we now stand on the shores of the sea and the same Teacher sees us, stops, and says to us, “Come, follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.” We cannot live in the story of the first fishermen. We must live in our story, the one that we are writing with our words and with our deeds each day, as we either decide to follow the path of the Galilean, or to go in the opposite direction, refusing to change our course, content to stay the same as we’ve always been.

Our world, as each of us surely knows, is a world in need of redemption, a world where the cries of the poor too often are not heard, where a blind eye is turned to the homeless, and where the hungry are dismissed as freeloaders. Is this, we ask ourselves, the world that God chose to create, or is this the world that we have created by our choices?

The Scriptures tell us that when God saw the darkness of the abyss, he brought light into it, his actions forever after a call to his creatures to become lovers of the light, not demons in the darkness. With his words, “Let there be light,” the good news was announced for the first time, offering us a world where the darkness is dispelled and where the light shines brightly.

But if that light is to shine still and if darkness is not to cover the earth again, as it did in the beginning, then we must decide to choose the light and turn our backs to the darkness. “A man must sometimes be forced to make choices,” the Jewish writer Chaim Potok once wrote, “for it is only by his choices that we know what a man truly is.”

In these urgent times, then, we have choices to make, not once, but continually, and in choosing one way or another, we become one kind of person or the other kind of person, ourselves gradually defined choice after choice, until it becomes clear as day that we have followed the way or we have walked away. “Come, follow me,” he continues to say, offering us the only way to save the world.

Years ago, a Jesuit priest summed it up well with these few words. He wrote, “Heroes don’t think they’re being courageous. They just think they’re doing what has to be done. In other words, they are acting in character. Now, ‘in character’ does not necessarily mean smartest or best, most prudent or holiest. It simply means most consistent.”

He continues, “Whether or not we’re aware of it, we spend our lives forming ourselves, both individually and collectively. Day after day, decision after decision, we make ourselves into the men and women we are: men and women who live primarily for themselves, or men and women who live primarily for others. Men or women with broad, generous and expansive vision, or men and women who are narrow and closed in upon themselves.”

He ends with this insight, “The upshot of this is that there are very few things we do or say that don’t matter.” He’s right, of course. So, as we hear again today the call of the first followers of the Galilean Teacher, we learn the importance of the decisions we make because, when all is said and done, our decisions make us.

–Jeremy Myers