John was clothed in camel’s hair, with a leather belt around his waist. He fed on locusts and wild honey. And this is what he proclaimed, “One mightier than I is coming after me.” (Mark 1.6-7)

A few years before his death in 1994, the Chicago newspaper columnist Mike Royko wrote a column about a fashion fad he was seeing on the streets, one that puzzled him. As he explained it, “Now we have sons and daughters of doctors, lawyers and business tycoons who look like they have just finished a hard day of putting up steel girders, when the truth is that they have just carefully dressed for an evening at the Hard Rock Cafe.”

The fad he was describing was the desire that kids with money had to wear clothes that, more typically, you would find on someone without money. Ascribing the trend to MTV, Royko described the apparel as making the kids “look like bums and poor urchins,” because of holes in the jeans, frayed slashes, and faded colors. And, as he pointed out, the real irony was that these tattered jeans cost more than brand-new jeans without holes in them.

He went on to say that he had documented evidence of “a genuine old bag lady taking pity on a rumpled wretch she saw on the street and offering to share her meager possessions, only to discover that he was a graduate business student.” Royko noted that, “Sly lad that he was, he accepted her offer of help, took a set of her long underwear and was the fashion hit at his fraternity’s next shindig.”

Concluding that clothes may indeed make the man, as the saying goes, he ponders the situation where prosperous young people can afford to spend extra money to look like they are downtrodden and pretend that they have calluses on their hands instead of their back sides. “Here,” he writes, “well-fed people compete to see who can look the most hungry.”

Royko was onto something and, had he lived a few decades more, he would have seen even more of the same fashion trend, torn and slashed jeans now the favored apparel of rich and spoiled kids who have never had to do manual labor a day in their life or have had to find a warm grate at night to sleep on.

Authenticity is a word we don’t use often anymore, and there may be a reason we don’t, the word meaning something or somebody that is genuine, real, legitimate. A person who is authentic dresses the part, his or her clothes not a fashion statement, but simply an expression of who they really are.

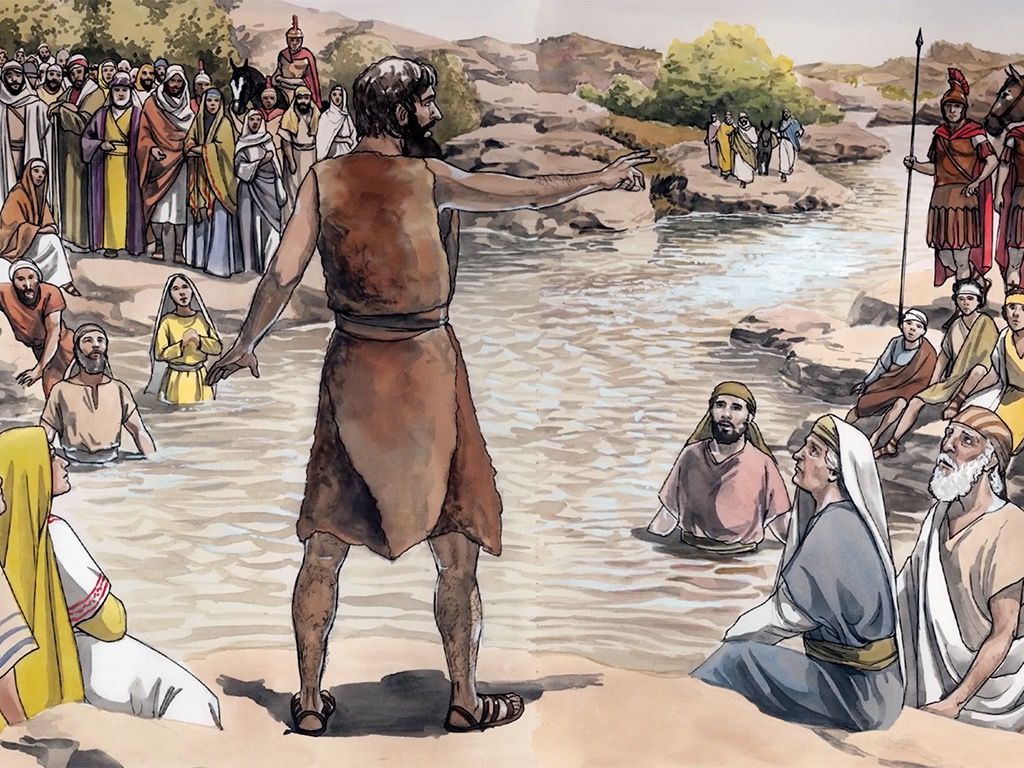

When hearing the selection from the scriptures that we have on this Second Sunday of Advent, many people become fascinated by the part that describes the clothes that John the Baptist wore, his camel-haired tunic, draped over his shoulders and held to his waist with a belt made from animal hide. Without a doubt, his clothes caught people’s eyes even in his own time.

But the thing about John was that he wasn’t putting on a show, his clothes weren’t some kind of haute couture. He was the real thing and he dressed the part. He lived in the desert, alone and apart, eating what he could find in such a desolate place, locusts and a bit of honey, it seems, what he subsisted on. And his clothes, the little he had, came from old carcasses left to dry in the desert sands.

The evangelist Mark calls him a messenger, an old word familiar to the people of Judea, a word often used to describe the prophets of old, whose job was to pass on messages from the Most High God to his chosen people. They were the mouthpieces of God, telling the people with their words what God was feeling in his heart.

Even today we are familiar with the word messenger, since we have bicycle messengers on busy city streets, delivering letters or packages for employers, dressed with safety helmets and carrying a mail pouch on their backs. With little adjustment required, John the Baptist was the Judean form of the bicycle messenger, hand-delivering to the people a message from an important person, in the same way that ancient prophets had done for centuries before him, and, like a bicycle messenger, his message was both urgent and timely.

Taking a step back, it is intriguing that Mark should begin his gospel with this word messenger, then presenting John as just such a one, dressed much the same way that the old prophet Elijah did, who also lived in the wild and, as a rule, looked the part of a wild man, while Mark’s later compatriots, Matthew and Luke, opted to begin their texts with a different type of messenger, angels, who–we can assume–dressed like celestial beings.

Yet, all three writers use the same word, angelon, which means messenger, from which we get the word angel. So, upon closer analysis, we could say John also could be understood as an angel sent by God, even if he didn’t float on the air or sparkle like the sun. Nevertheless, he was a messenger, used by Mark to begin his gospel in much the same way as Matthew and Luke use angels to begin their gospels.

In the fifth century, another man, later called a saint, came on the scene. Hilary of Arles was named a bishop of the church when he was 29, but, unlike his contemporaries of episcopal rank, he did manual labor to earn money for the poor, sold sacred vessels to ransom captives, and traveled everywhere on foot, always wearing simple clothing. He once wrote, “Everything that seems empty is full of the angels of God.” Having his own experiences with a life of austerity, as did John, Hilary became the patron saint against snake bites.

John’s task as a messenger was to convey a single word from the Most High God, metanoia, a word often translated as repentance, but just as rightly understood as reversal, the concept being that people needed to turn around their lives, living in a different way, turning their backs on evil intentions, and, for once in their lives, becoming authentic human beings.

Authenticity, as we have said, is not a word often used, probably because it is a word not often seen. Authentic people are few and far between, most people preferring to pretend to be somebody they aren’t, their ruse hidden behind coat and tie or beneath pearls and formals, too often playing a game of charades. The gifted poet, Carl Sandburg, begins his poem, “The Eastland” with this verse, “Let’s be honest now/ for a couple of minutes/ even though we’re in Chicago.”

When John stepped out of the desert, a message from God tucked underneath his sweaty armpits, he said the same thing, asking the crowd in front of him to be honest for a couple of minutes, looking at who they really were, stripping themselves spiritually naked to see what they had become. And in those few minutes of honesty, he urged them to reverse their ways, becoming who they were created to be, children of the Most High God, not frolicking dancers around a golden calf.

John’s message never grows old because the times never really change, humans still struggling with authenticity, preferring lives of duplicity, not taking a few minutes to be honest with themselves. These days of Advent, therefore, are a gift to us, days of honesty placed before us for our taking, John the Baptist begging us to make a u-turn on the road before we end up in an ugly place, a place where we don’t even recognize ourselves anymore.

Perhaps, the writer Margery Williams, in her classic children’s book, The Velveteen Rabbit or How Toys Become Real, offers us the path to authenticity. In it she tells of a conversation between two toys on the shelf of a little boy’s room, the skin horse and a rabbit made of velveteen. That conversation is as good a meditation for this season of Advent as any other. She writes:

The Skin Horse had lived longer in the nursery than any of the others. He was so old that his brown coat was bald in patches and showed the seams underneath, and most of the hairs in his tail had been pulled out to string bead necklaces. He was wise, for he had seen a long succession of mechanical toys arrive to boast and swagger, and by-and-by break their mainsprings and pass away, and he knew that they were only toys, and would never turn into anything else. For nursery magic is very strange and wonderful, and only those playthings that are old and wise and experienced like the Skin Horse understand all about it.

“What is REAL?” asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender, before Nana came to tidy the room. “Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?” “Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.”

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit. “Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.” “Does it happen all at once, like being wound up,” he asked, “or bit by bit?” “It doesn’t happen all at once,” said the Skin Horse. “You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept.

Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.”

“I suppose you are real?” said the Rabbit. And then he wished he had not said it, for he thought the Skin Horse might be sensitive. But the Skin Horse only smiled. “The Boy’s Uncle made me Real,” he said. “That was a great many years ago; but once you are Real you can’t become unreal again. It lasts for always.”

The Rabbit sighed. He thought it would be a long time before this magic called Real happened to him. He longed to become Real, to know what it felt like; and yet the idea of growing shabby and losing his eyes and whiskers was rather sad. He wished that he could become it without these uncomfortable things happening to him. . .

One evening, when the Boy was going to bed, he couldn’t find the china dog that always slept with him. Nana was in a hurry, and it was too much trouble to hunt for china dogs at bedtime, so she simply looked about her, and seeing that the toy cupboard door stood open, she made a swoop. “Here,” she said, “take your old Bunny! He’ll do to sleep with you!” And she dragged the Rabbit out by one ear, and put him into the Boy’s arms.

That night, and for many nights after, the Velveteen Rabbit slept in the Boy’s bed. At first he found it rather uncomfortable, for the Boy hugged him very tight, and sometimes he rolled over on him, and sometimes he pushed him so far under the pillow that the Rabbit could scarcely breathe. And he missed, too, those long moonlight hours in the nursery, when all the house was silent, and his talks with the Skin Horse.

But very soon he grew to like it, for the Boy used to talk to him, and made nice tunnels for him under the bedclothes that he said were like the burrows the real rabbits lived in. And they had splendid games together, in whispers, when Nana had gone away to her supper and left the night-light burning on the mantelpiece.

And when the Boy dropped off to sleep, the Rabbit would snuggle down close under his little warm chin and dream, with the Boy’s hands clasped close round him all night long. And so time went on, and the little Rabbit was very happy–so happy that he never noticed how his beautiful velveteen fur was getting shabbier and shabbier, and his tail becoming unsewn, and all the pink rubbed off his nose where the Boy had kissed him.

–Jeremy Myers