Then they will answer and say, “Lord, when did we see you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or ill or in prison, and not minister to your needs?” He will answer them, “Amen, I say to you, what you did not do for one of these least ones, you did not do for me.” And these will go off to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life. (Matthew 25.44-46)

A dozen or more years ago, the writer Jason Love shared a story he had picked up somewhere about a man named Mike who had been injured in an automobile accident, leaving him seriously handicapped and largely dependent on others. His neighbors were Yahaira and her husband, with Mike depending on Yahaira to help him with some chores and simple tasks in his house.

One evening, when Yahaira had gone somewhere, her husband, an editor and writer, was busy at his laptop, trying to get a news article in by deadline, working from home that evening, when the phone rang. It was Mike, asking if Yahaira was home. “Hi, Mike,” he said, resting the phone on one shoulder while he continued to work on his computer. “Yahaira’s out this evening.”

“Oh, I see,” Mike said. “Well, okay, then.” There was a pause, no sound except for Mike clearing his throat. “Sounds like you’re pretty busy.” Still focused on the keyboard, the husband answered Mike, “Yeah, I am, Mike. I’m on a deadline. Can I help you?” It was more a rhetorical question than a real question.

“No, it’s okay,” Mike answered. Another rhetorical question as the writer hit the keys on his laptop, “You sure?” “Yeah,” Mike said, “I’ll just wait till Yahaira gets home.” With those few words, the conversation ended. The husband didn’t remember if he had said goodbye to Mike or not, telling himself that if Mike really needed something, he would have spoken up.

Sometime the next day, when Yahaira and her husband were together, she told him why Mike had called the evening before. He needed someone to button his shirt, his fingers so mangled by the accident that he couldn’t get the buttons through the holes in the shirt by himself. Hearing his wife explain the purpose for Mike’s phone call, her husband took a deep breath, a heavy feeling in his gut and an odd twitch in his spine.

Unpleasant and unsettling, a thought crossed his mind, settling in his stomach, twisting and turning. “If I don’t have two minutes to button a neighbor’s shirt,” he asked himself, “which one of us is disabled?” The question stayed with him for weeks afterwards, prodding his conscience, probing his heart, the answer all too clear to him. Awareness, he realized, sometimes comes too late.

He needn’t feel too bad. That lack of awareness is not only his, as the learned Rabbi from Galilee makes perfectly clear in the last story that he tells, as recorded for us in the Gospel of Matthew. A part of what has become known as “the final discourse,” the story is the fourth and final in a series of stories that the Rabbi tells, each one emphasizing the need to be prepared for the master’s return.

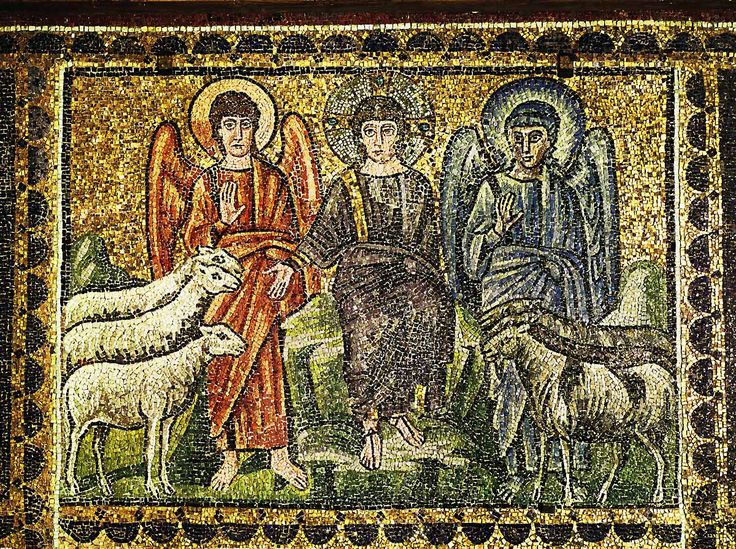

In this story, the Rabbi tells of the final judgment, when the King of the Universe returns, judging the nations for their just or unjust deeds, using the image of a shepherd separating the sheep from the goats, in this way providing the name that is commonly associated with the story, the parable of the sheep and goats.

Stark, simple, even solemn, the story tells how the King moves the sheep to his right side and the goats to his left side, speaking first to the sheep, inviting them to share in the divine kingdom because they gave him food when he was hungry, drink when he was thirsty, a welcome when he was a stranger, clothing when he was naked, care when he was sick, and a visit when he was in prison.

Surprised and perplexed by the praise, the righteous are left to ask, “Lord, when did we see you hungry, thirsty, naked, sick, or in prison?” The answer comes back to them, “Whatever you did for one of the least brothers of mine you did for me.” His words indicate that their acts of kindness towards the least, the last, and the lost did not go unnoticed by him, identifying himself with the unfortunate ones in the world.

Turning then to those on his left side, the King of the Universe offers sharp and stern condemnation, “Depart from me, you accursed,” he says to them, putting before them their blindness to his need. “I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me no drink, a stranger and you gave me no welcome, naked and you gave me no clothing, ill and in prison, and you did not care for me.”

Startled and shocked by the sentence given to them, they plead for leniency, asking him, “Lord, when did we see you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or ill or in prison and not minister to your needs?” As before, his answer identifies him with those who suffer in this world, “What you did not do for one of these least ones, you did not do for me,” he says, destroying their defense, pointing out their lack of awareness of his presence in the poor and in the downtrodden because they breezed by, too busy, too proud, too selfish to lend a hand to help.

Surely of interest to us, the question asked by both the righteous and the unrighteous is the same, “When did we see you?” with the word see being at the center of the question. When examined more closely, the word actually used in the text implies more than a surface sighting of someone, more than a casual visual image of something passing in front of us.

Instead, the word carries a sense of a deeper recognition of the person, our words stare or discern a closer intent of the passage. Or, as we might say, an awareness of the other, implying some knowledge in addition to the perception of the person in front of us, our slowing our steps, pausing on our path, to really look at the person, becoming in that moment aware of someone in need, someone who reaches out to us, someone who depends on us for help.

Some years ago, the actress Ellen Burstyn, known for her getting deeply into her roles, spent three days sleeping in a cardboard box on the streets of New York, so that she could experience how it really felt to be homeless. Later, she told of an incident that happened to her while on the streets, explaining that she had gone up to a restaurant that had outside tables, where two women were eating. Approaching the women, she said to them, “Excuse me, but I have to take a subway and have no money. Can you spare a dollar?”

She said one of the women reached into her pocket and gave her a dollar. As she walked away from the two women, she felt relieved that she had gotten the dollar. But, as she said, she felt tears running down her cheeks. And why the tears? Because, as she said, “she hadn’t even bothered to look at me.”

And therein is the crux, the failure to see the person in front of us, the one in need, that lack of awareness that causes the hungry to have no food, the thirsty to have no drink, the near-naked to have nothing but rags on their back.

It is an “awareness test” that the story the Rabbi tells poses, the goats failing the test, never glancing at the man digging his meal out of the dumpster, or giving a second look to the woman walking the street with only one shoe on her feet, while the sheep pass the test, truly seeing the other person in need, stopping to hear the cry for help, seeing the sadness in the eyes of the single mom with nowhere to go.

Of course, the exemplar of someone having this keen awareness of others was Rabbi Jesus, who saw the leper begging him from the side of the road, saw the widow weeping copious tears as she buried her son, or saw the woman whose sickness had put her on the doorstep of death. When he looked at each of them, he saw, not an “it,” some disease or some delay, but saw a child of God, beloved as he was by his Father.

As the hungry yearned for something in their stomach, he did not look away or send them away, but looked at them with an intensity of love, and as the short-statured tax-collector dangled from a limb of a tree, he stopped, stared, and saw into the depths of the man’s heart, finding it redeemable, and as the thief begged of him for the simple kindness of remembering him, both of them crucified side by side, he turned to see the man, his awareness of another suffering soul not dulled by the pain of the nails in his own hands and feet.

That same awareness of others he now asks of his followers, asking them to open their eyes to the poor and to the prostitute, to the sick and the sinner, to the foreigner and the unforgiven, answering their cries and their groans and their prayers with kindness, with generosity, and with mercy. As he saw the image of God on the lost souls of this world, he commanded those who would continue his mission to find his image behind the faces of the forgotten and the forsaken.

In a sermon he preached shortly before his death, the Jesuit priest and theologian Walter Burghardt, who also understood that awareness implies a special way of seeing others, seeing them not as problems, but as persons, posed this challenge to Christians. He said, “The Christ of the first Christmas is no longer a child. He has grown up; he has risen from the dead.”

“But his place is taken, the manger is filled by other Christs. What will I see,” he asks, “when I kneel before the Christmas crib,” posing the same question to us. He answers, “It is no longer a cherubic little Christ that is enfolded in Mary’s warm arms. It is an infant born with AIDS; a child with Down’s syndrome who will never really grow up; a wee one riddled with bullets from a passing car; a black Christ abandoned by her father; a brown Christ bloated from hunger, eyes empty of hope.”

With those words, Father Burghardt makes clear to us the answer to the question that those to the right and to the left of the King pose when they ask him, “When did we see you?” The answer is simple. We see his Divine Presence whenever we become aware of “the least ones,” as Rabbi Jesus calls them, the ones who the world discards and dismisses, the very ones who the world crushes and crucifies.

Attending a convention in Boston one year, the speaker Cavett Robert tells of an experience he had while there. Already in a foul mood because of a mix-up with his room, he was in a hurry to get to the airport to catch an earlier flight. Taking the elevator to the lobby, it stopped at the seventh floor, but nobody stepped inside. “Come on in,” he said, assuming someone had pushed the button.

Nothing happened. Again he said, his voice curt and impatient, ”Come in. Let’s get the show on the road.” Nothing happened. Finally, he muttered out loud, “Come on in. Let’s go. I’ll be late.” At that moment, a man with a white cane, completely blind, stepped into the elevator, his step cautious, feeling his way inside.

Robert said he felt he had to say something. “How are you today?” he asked the blind man. A smile on his face, the blind man answered, “Grateful, my friend, grateful.” Robert couldn’t say a thing. Later, speaking of the experience on the elevator, he said, “Here was a man blessing the darkness while I was cursing the light. I found myself,” he said, “that night in my prayers asking that someday I might see as well as that guy.”

Honestly, it is a prayer we all might put before God, asking him that we might see as he sees, becoming more aware of the least ones in the world, in this way changing us from goats into sheep, because, as in the story the Galilean tells, the sheep are called blessed, while the goats are called cursed.

–Jeremy Myers