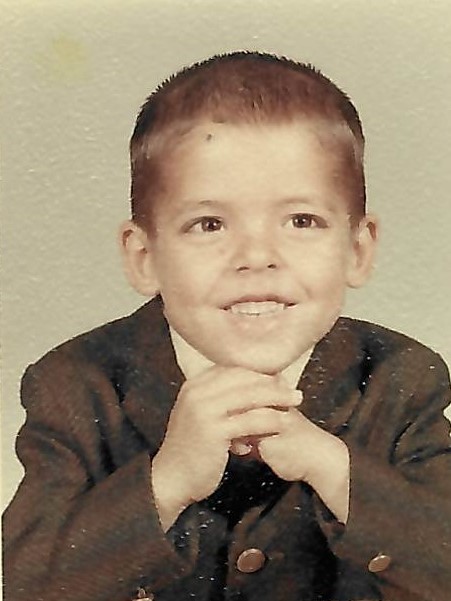

When he entered the world, he carried a lot of weight, over ten pounds, in fact, which is a helluva ham if you’re in the meat aisle of Walmart. Today, he still carries a lot of weight, this time not in pounds, but in influence. Back when he was ten pounds, we called him “Baby Boy,” because he was the baby boy, a lack of imagination on our part, I admit now. Bringing the number of boys in the family to a neat half-dozen, the name lasted long after he was out of diapers, because he was still the baby boy, and our imagination had not improved with the years.

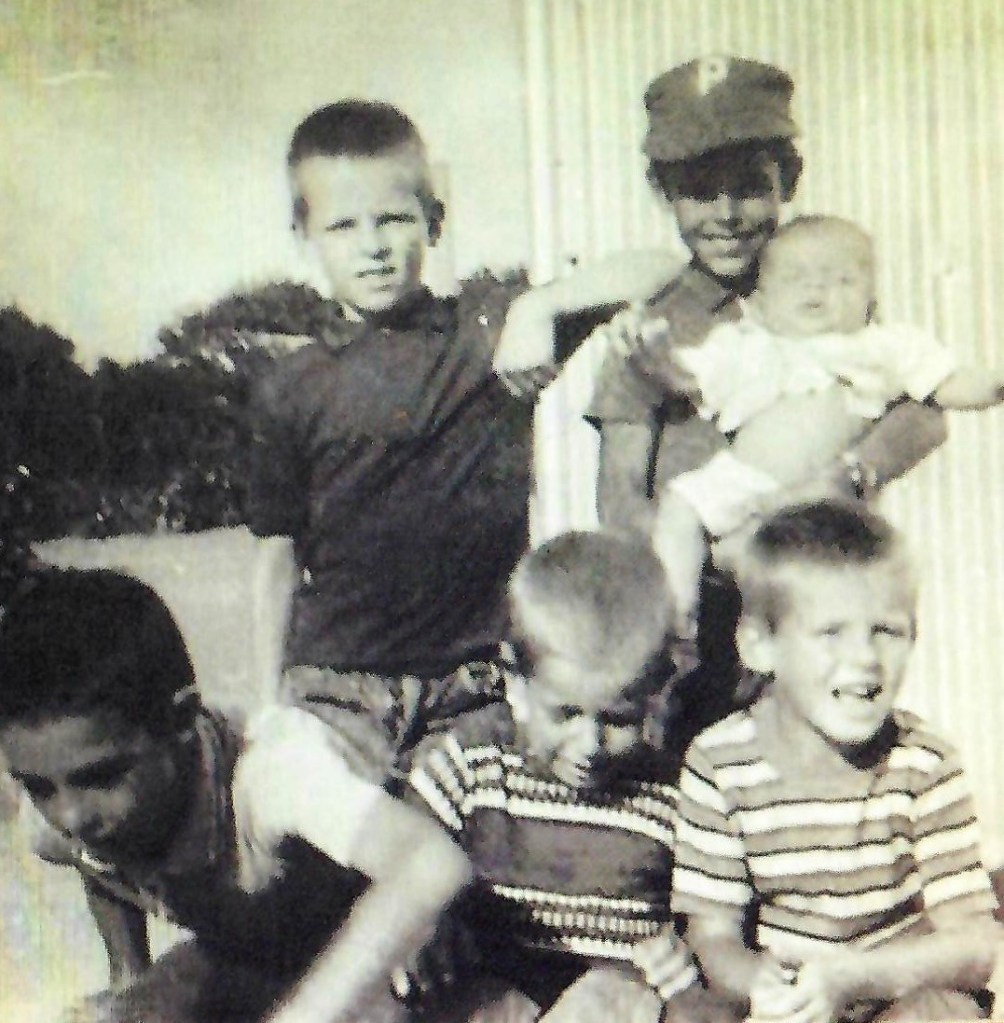

Mama was proud of him when he was born that Friday morning, April 16th, a pride she kept till her dying day. Unlike his brothers, an unimaginative lot, she named him John, her reasons unknown to me, but probably naming him after John Kennedy, the popular president, which also may explain why John was the second most selected name for boys in 1965. But I would never say Mama lacked imagination. His older brothers took to him easily, becoming guides and guardians, for better or for worse.

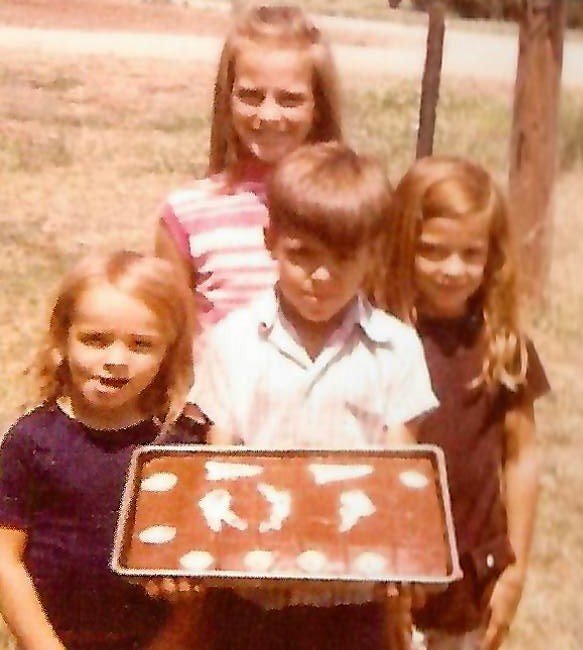

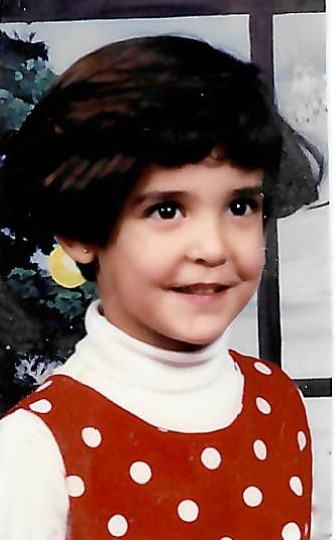

That is not to say his sisters didn’t take to him also, because they did. They laid claim to him like they’d discovered the proverbial pearl of great price, probably because he was the only boy in their age range, Mama deciding to have boys at the top half of the ladder and girls at the bottom half, with one exception in the top rung, and Baby Boy the exception on the bottom rung. He was nestled among those girls like a beetle in mud, no offense to those sisters.

With nine older siblings–four more would follow after him–he received plenty of love, making for his pleasant personality, I would like to think, although it may simply have been genetics, his personality the most like Mama’s, even-tempered, good-willed, warm-hearted. His personality, fixed in the early years, would never change. Even now, fifty-five years later, he still brings Mama to mind in the way he lives, a happy, happy-go-lucky, hopeful guy.

Busy with feeding and watering and watching a houseful of children, Mama depended on us to keep an eye on Baby Boy, while she kept an eye on us, knowing we could get in much more trouble than he could, our years giving us an advantage over him in adventuresome living. Late at night, as she swept and mopped the linoleum floors, tracked upon by tiny feet throughout the day–a religious ritual for her, refusing to go to bed with dirt on her floors–she would have my big brother rock Baby Boy to sleep, while she finished her house cleaning.

Eleven-years-old at the time, big brother sat in the old, overstuffed, worn-out chair that rocked with a loud squeak, wrapping his arms around Baby Boy, soothing him as he cried, giving him his bottle, and assuring him that his world was safe, even if his mama was in the next room. It takes no stretch of the imagination–something in short supply, as I said–to believe those late nights spent in the living room, big brother rocking Baby Boy to sleep, built a bond between them, a link between brothers that is still unbendable and unbreakable.

As he grew, as we all must do, the pet name Baby Boy didn’t fit him as well anymore, only because he wasn’t sucking milk out of a bottle or wetting his diaper anymore, so we adapted, accepting John as his name, or, when imaginative, coming up with other nicknames, if the shoe fit and, more importantly, if he went along with it.

However, fight it as he might, he would always have Baby Brother as one of his names, since he was at the tailend of the boys, and, while he might grow to be 6’2”, standing inches above most of his brothers, he was still our baby brother.

My sisters, to this day, take all the credit for the man Baby Brother has become, claiming it was their influence that shaped him, surrounded as he was by all of them, which, as I see it, is like a boa constrictor boasting it should be praised for how good the monkey tasted just because it had squeezed the life out of it.

But, in fairness to them, they did teach him important life skills, such as how to weather storms, their temperaments ever changing from raging storms to sunny still days, how to admit defeat in an argument, their belief being that the loudest voice wins in the end, and how to find his way around a kitchen, their attitude being that God didn’t tell Eve she had to do the cooking for Adam.

I do not deny their influence in any of these ways, but I would remind them–gently–how he also doesn’t like a noisy room. Where that came from, I suppose, is anyone’s guess, but surely not because of them. To their credit, they respect his desire for quiet, especially when he eats his lunch, quick to hush noisy grandchildren, somewhat less quick to shush themselves.

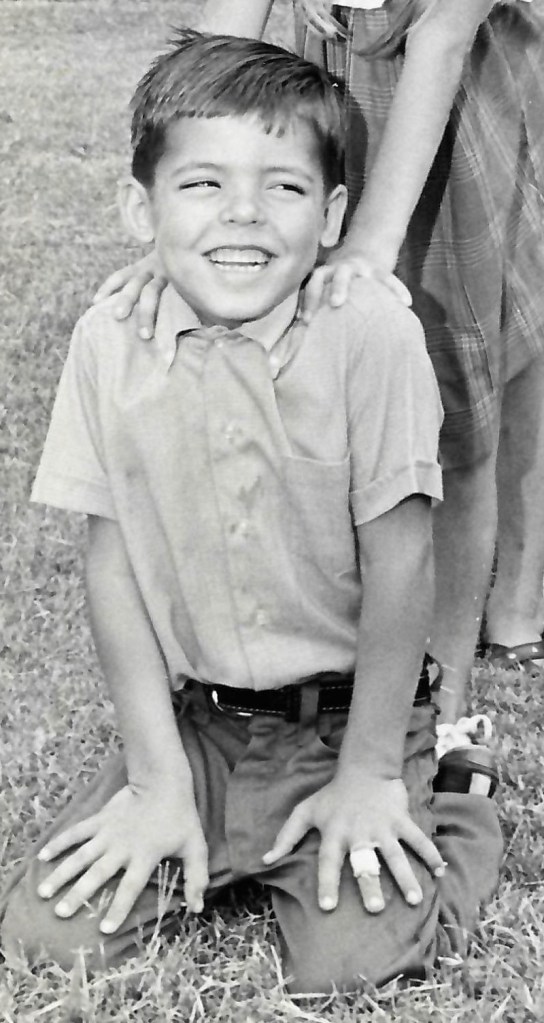

As he was growing up, Baby Boy’s best friend was his first cousin, Son, a nickname again, as you can see, calling for no imagination, the two of them perfectly suited for each other, never a dare not taken, never a day not ending late, never a dirt road not walked for miles on their bare feet. Hampered neither by fright nor by flight, their amusements ranged from fishing in nearby watering holes with cane poles to shooting rattlesnakes with Daisy bb guns.

As close to Tom and Huck as anybody could be, except for the century between them and except for the Brazos River being a poor substitute for the Mississippi River, the two of them spent many summer afternoons on the riverbed, spooking mud swallows or catching tadpoles, their torsos shirtless and sunbaked. I don’t recall any ill intent ever part of their escapades, everyone I know willing to agree that rattlesnakes are a menace.

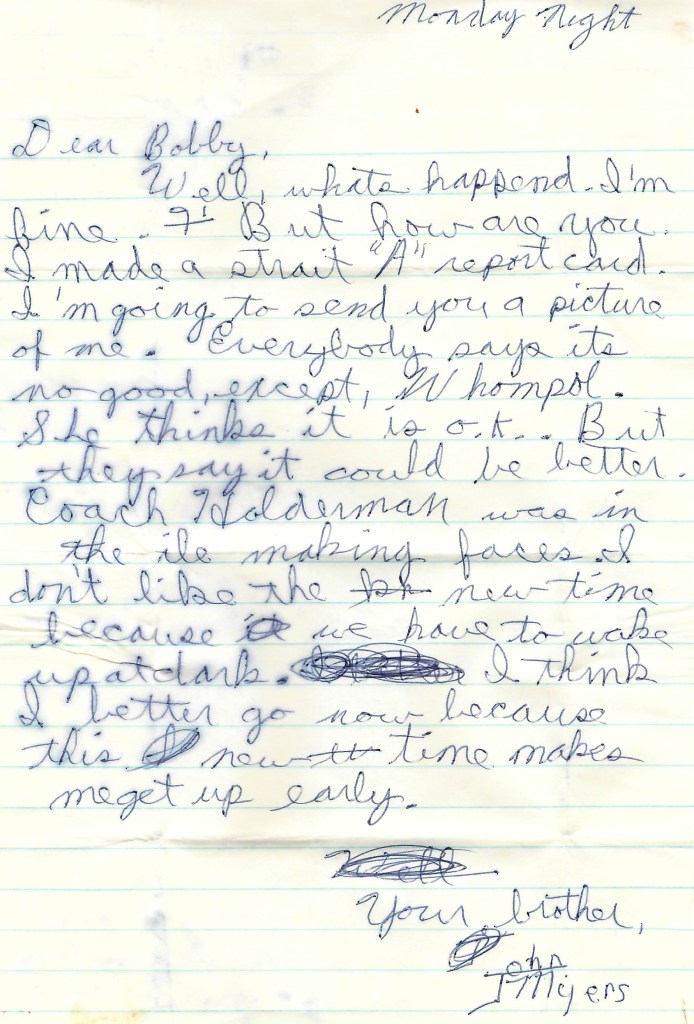

For them, entering school put a lock on some doors, but they managed to sneak through a door or two. In one letter he wrote me when he was 11-years-old and I was at college, my baby brother assured me he had made all A’s on his report card, which I do not question, but wonder why he misspelled so many words in his letter. The safe conclusion, I suppose, is that spelling was not part of the curriculum that year. Anyway, spell check has solved that problem for him.

By all measurements, his boyhood was a good one–Mama was never one to clip young wings– watching his older brothers and what they did, for good and for ill, in this way learning to play football from them, learning to cuss from them, and learning how to chew tobacco from his cousin. His only complaint, as I recall, was that he never got what he wanted at Christmas, but I don’t remember what it was exactly he wanted for Christmas, the answer to that question possibly explaining why he didn’t get it.

Somewhere along the way, probably in high school, he learned how to be funny, with quick wit and great one-liners, his sense of humor becoming finely honed and his delivery of punchlines nearing perfection, a skill that has not diminished with the years, his chuckle always on the cusp of escaping, his witticism always a part of every conversation, and his repartee always unequaled by anybody in the room.

The day after graduating from high school, my baby brother sat down at a desk in my dad’s office, learning the ropes of the trucking business, assuming more responsibility as the months moved on, becoming in time the primary dispatcher, a high pressure job that required finding hauls for the truckers and ensuring that they got to their destination on time.

Soon, he could be seen carrying a rolled-up piece of paper, edges curled, pencil-smudged, with him everywhere he went, every load on the road written down, the paper a quick reference for him wherever he was, so he could be ready with an answer when the phone rang. I rarely saw him eat lunch without having to take out that paper, roll it flat on the table, and communicate information to a trucker on the road.

Good-humored and mild-mannered, he became well-known to companies on the other end of the phone calls, earning their trust and their business, in time expanding the truck company, seeing it become more than Daddy ever envisioned. He stayed behind that same desk for over 30 years, only in recent years turning over the reins to a nephew, while he took to the road in one of the trucks, the change of pace good for his sanity, he would say.

Two-and-a-half years after graduating from high school, he married, becoming a husband and a family man, surely ready for these responsibilities because of the training his sisters had given him, as they would be quick to point out, and, admittedly, he is the best at both, to their credit or not, depending on how you choose to award credit in these matters. As I suggested before, nature is not always outgunned by nurture.

When his second daughter entered pre-K, he’d pick her up from school at lunch, bringing her back to the office where he worked. She’d sit on a sofa or at a desk, passing her time, staying close to her daddy. When I’d come in, I’d have her roll my pennies, giving her something to do, always letting her keep the money, payment for her doing the work. Tutored by her daddy, or smart like her daddy, soon she asked me if she could roll my dimes.

Like most every boy raised in the rural parts of Texas, my baby brother had a dog, over the years any number of them, Snowball, Lexi, Prissy, Gus, to name some of them. Small and snappy, Lexi and Prissy were mainstays in the office, Prissy in an empty chair, and Lexi always snuggled behind my brother’s back in his chair. Coming into his office, I’d ask where she was. Standing up, he’d show me she was resting in the small of his back. Never a more content dog have I seen.

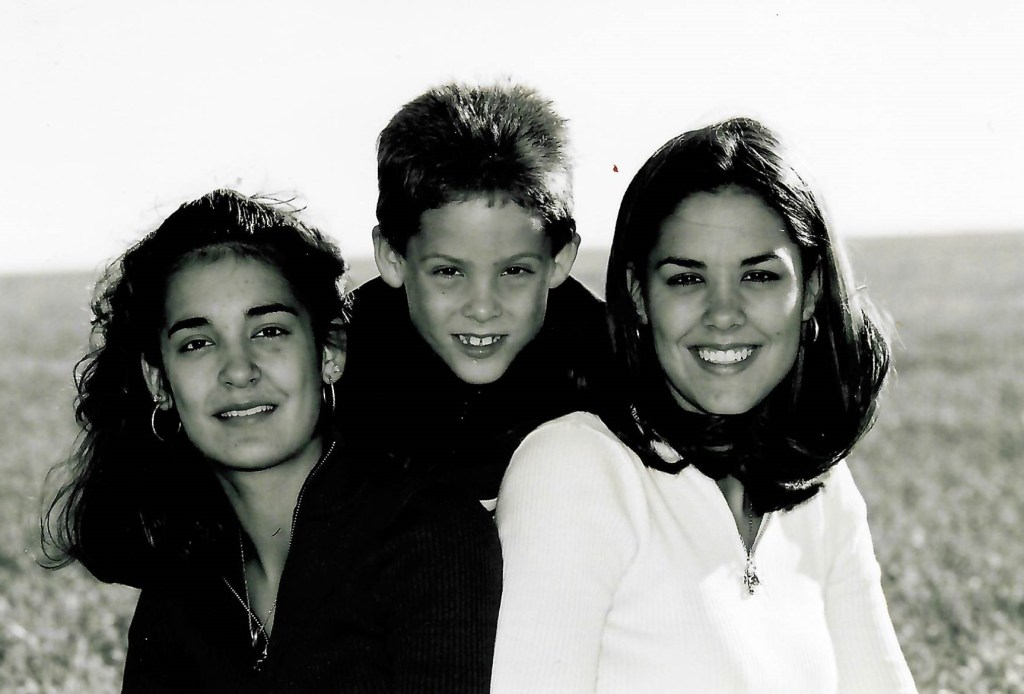

Inheriting Mama’s disposition, especially her good nature, he raised his two daughters and a son, parenting them with the same freedom and trust that she had raised him, a good formula, as time has shown, his son Jake now following in his dad’s footsteps, also working for the trucking company, his two daughters working in education, all three having the same easy-going, good-hearted, well-mannered disposition of their mom and dad.

Once upon a time, watching Jake shoot some baskets in his backyard, stopping regularly to look at a piece of paper–he was in elementary school–I stopped and asked what he was doing. He explained he was studying his spelling words. Every time he got one right, he explained to me, he rewarded himself by taking a shot at the basketball hoop. That was the day I learned he spelled like his daddy.

A hard-worker, diligent and disciplined, my baby brother took on a second job for many years, driving a truck for the local cotton gin, going into the fields to retrieve the cotton modules after the cotton bolls had been stripped from the stalks, leaving after office hours and working until midnight. His wife, knowing how dog-tired he was, often went in the truck with him, to keep him company and to keep him awake.

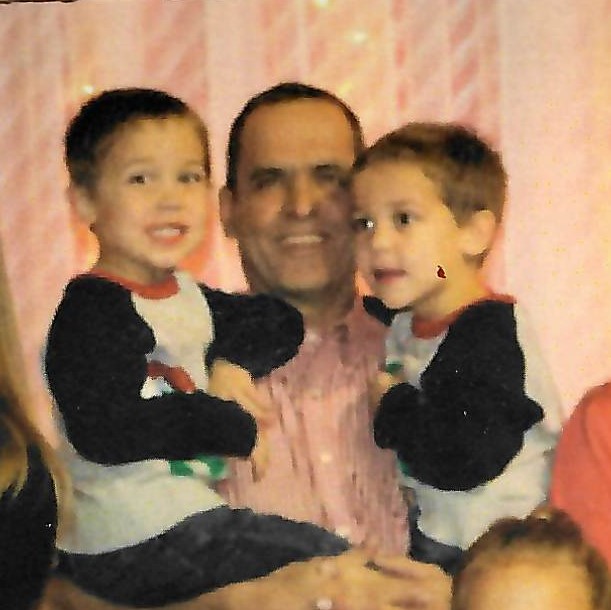

When his girls got married, grandchildren began to show up on family pictures with regularity, now eight of them, and more to come, I am sure, since Jake isn’t married yet. When Katie had twin boys on her daddy’s birthday, I called to congratulate him. Taking the call in the same room with his newly minted twin grandsons, he told me it was the best birthday present he could ever have. I have come to see he meant it, every time they are together looks like it is a birthday party, laughter and play filling the air. The only thing missing is helium balloons.

Since all his grandkids like fresh fruit, Poppies–the name they call him, a smidget more imagination expended in the name than in his earlier nicknames–likes to bring them to my peach trees when they come in for a visit during the summer, allowing them to pick their own peach from the tree, their height about right to grab low-hanging fruit.

Hearing his granddaughter say to him one day, “I want an apple,” I asked him why he didn’t tell her it was a peach, not an apple. True to form, he smiled and answered, “She has plenty of time to learn it’s a peach.” The same attitude carries over into his grandsons’ rich vocabulary, their ears attuned to Poppies’ choice of words, quick to repeat them, as children do.

Walking up the steps to Mama’s house one day, I saw the pair in an outdoor swing, waiting for lunch. As I passed by, one twin turned to the other, saying, “You’re a shithead. You are not my best friend anymore.” While correcting him may have been the better course, I chose a chuckle instead. Later, telling his Poppies what I had overheard, he simply said, “He’ll have time before going to school to figure out what not to say.”

At another time, his oldest grandson, sticky juice dripping down his chin, hearing me say it was a plum he was chewing up, answered–chunks of fruit in his cheeks–”It’s plumlicious,” that word worthy of entry into the new edition of Merriam-Webster’s dictionary. Like me, they were disappointed when the peach trees didn’t have apples on them this past summer, the late frost in April hitting the trees hard. Still, they walked past the trees, searching the branches, sure they could find an apple somewhere hidden in the leaves.

Fifteen years ago, my baby brother gave us the scare of our lives and–in that moment–we learned how truly special he was. Suffering stomach problems, he was diagnosed with a tumor in his pancreas, the removal required, the prognosis not good. As with those moments in life when life stops, I remember the time and the place where I was when I received the phone call.

The next week, accompanying him to visits on the same day with two surgeons in Dallas, he made one request of them. “I would like to live to see my ten-year-old son graduate from high school.” One surgeon’s response was unpromising, stating he was 99 percent sure the tumor was malignant. The second surgeon, hearing my brother’s request, answered, “I promise you will.” We chose the one who made the promise, my brother saying to me, “I’ll go with the guy who offers hope.”

On the day of surgery, which lasted from dawn to dusk, Mama was in the church at the crack of dawn, and she never left until it was night, praying to Almighty God to perform a miracle, letting her baby boy live. Always a woman of prayer, on that day she prayed as I never had seen her pray before, never taking a break, never taking a full breath, continuously beseeching the Lord on behalf of her son.

Late that afternoon, sometime after four o’clock, I swear I knew the moment when her prayer was answered, a feeling of peace coming to me, so strong it was as if a voice from heaven had spoken to me, telling me all would be well. And it was. The surgeon was able to keep his promise on that day because God answered the prayers of a mother who begged for her son’s life, as close to a Biblical story as I’ve ever seen in all my days.

She never forgot that day and she never forgot what God had done for her. She called it a miracle, believing God had stepped in, changing the tumor into a benign one, allowing her baby boy to continue with his life. And she never stopped thanking God for his goodness, continuing her prayers of thanksgiving through the next decade and more after.

Her baby boy also never forgot her prayers for him. When she was old and in need of assistance, he was there for her, as she had been for him, taking a turn every Tuesday to stay with her, coming to her house after work and not leaving until her night caregiver arrived hours later. He fixed her supper for her. He shared stories from his day with her. He quietly worked his crossword puzzles at the table while she prayed her evening prayers, each of them grateful for the other, both grateful to God for their time together.

Years ago, Mama tended to the flower beds around the church, seeing that the plants were watered regularly, weeding the beds when needed, wanting the exterior of the church to be as beautiful as the interior. In later years, after she was unable to do it any longer, her baby boy took over the job, he and his wife keeping up the flower beds with the same, if not more, devotion as she had done.

It was just one more thing that he and his mama shared.

–Jeremy Myers