When my grandma died at the age of 84, her household possessions were picked over and plucked and packed up by her children, most of whom met in her home after her funeral to do the brutal work of emptying the house, the reverse of filling a house, the joy of moving in things replaced now by the sadness of moving out things.

Not having the stomach for such a desecration, necessary but not nice, I stayed away, although I had spent most of my growing-up years in that house. It was enough for me to have seen my grandma taken from me. To see the emptying of her house was more than my young heart could take.

Afterwards, when most everything had been removed, I walked through the house, emptied of her spirit and her things, looking for the familiar feel I had always found there, but unable to find it, everything suddenly unfamiliar, an emptiness entering my heart equal to the emptiness of that house. Four walls remained, although nothing remained on them.

For some inexplicable reason, her writing desk was left behind where it always had been, butted against the north wall of her sewing room, suddenly very small in the empty space of that room where so much had once stood. Since no one apparently had wanted it, I claimed it as mine, and fifty years later it is still mine, resting in one of the rooms in my house, a reminder of my childhood and of the grandmother who had filled those years with love and care, with stories and memories.

For the most part, the desk is unchanged. Were I to guess, I suspect it was left behind because there was nothing particularly attractive about it, an old and simple desk that Grandma must have used for many years, something she had long before I entered the picture. I say this because the desk on which her sewing machine had rested, a newer desk, still unvarnished and unpainted, was taken by one of my uncles, who gave it a coat of something or the other and turned it into an attractive piece of furniture.

Grandma’s writing desk, on the other hand, looked unsteady and well-used, weak and worn out. Fortunately, it also was light-weight, so it was easy for me to carry in my arms, its length no longer than the stretch of my small arms. Shortly after claiming it, I gave it a new coat of brown paint, which changed the appearance little, if any, and I kept guard over it through the years, like a mother kildee would her nest of new eggs.

Although I cannot prove it, I am sure Grandma had brought the desk with her from her farmhouse when she moved into town, the years very evident on it, and she used it in her new home in much the same way she had used it in the farmhouse. She wrote letters on it, pulling her small tablet of lined paper from the top right drawer, taking her bulky pen from the pen holder atop the desk, putting pen to paper and, in this way, transporting words into space and time.

That, of course, is the purpose of any writing, providing us with a means to transmit words and ideas across space and time, a human activity with a very long history, over five thousand years, give or take. It was a linear route, more or less, beginning with wooden blocks cut from trees with images carved into them, progressing to clay tablets, such as those the Lord God used when he dabbed his fingers into the wet clay to write the Ten Commandments for Moses, then onto papyrus, sheep skin, vellum scrolls, paper, and–for now–digital inscription. A pre-K child’s first attempted scrawling of his name to a high school senior’s effortless signature, we could say, might be a condensed version of those five thousand years of the history of writing.

Anthropologists like to point out that writing systems never stand still, meaning there is constant change in the ways and means, even if our alphabet seems either strong or stubborn or surly enough to have withstood these changes over the four thousand years since people stopped drawing pictures and started using letters to signify someone. Think about this fact. What we now input on the keyboard–words formed from letters–the Phoenicians carved into blocks of wood–the letters more or less continuous over the long timeline.

Grandma had a distinctive handwriting that, I am led to believe, resulted from her learning to write in German before she had learned to write in English, her alphabet letters carrying many of the same characteristics still associated with German, large, bold, strong letters, intricate enough to require slow or a second reading, at least until one became familiarized with it. She also wrote with a slow and careful script, unlike us, whose indecipherable scrawling shows our rush to get to the finish.

As a rule, Grandma wrote her letters in the evening, when the sun went down, using daylight for chores and cooking, for weeding and working outdoors. When dark descended, she’d sit at her desk, using the dusk hours to communicate with her children who lived far away or with her friends who had moved far away. As she wrote, she occasionally would look up to see the laminated death notice of her departed husband, Tony. She found solace in keeping his picture atop her desk where she could see it as she wrote her letters.

On most evenings, I would usually be at the kitchen table, doing homework, but I also often would go into her sewing room, stand beside her as she wrote her letters, asking her way too many questions, and, in the process, learning a lot about her friends and about her. She never read the letters to me and I didn’t read them over her shoulder, not that she would have objected, but they held little interest to me at the time, since I was still at the Dick-and-Jane reading level.

However, curious as any child, I’d ask to whom she was writing her letter, the answer varying, but some names stay with me, such as Sister Claudia, a nun who had grown up with Grandma before going to the convent and who had come back to her hometown to teach the children a few years earlier, but now was back in Arkansas. From the frequency of letters back and forth between them, it was clear that the bond was strong.

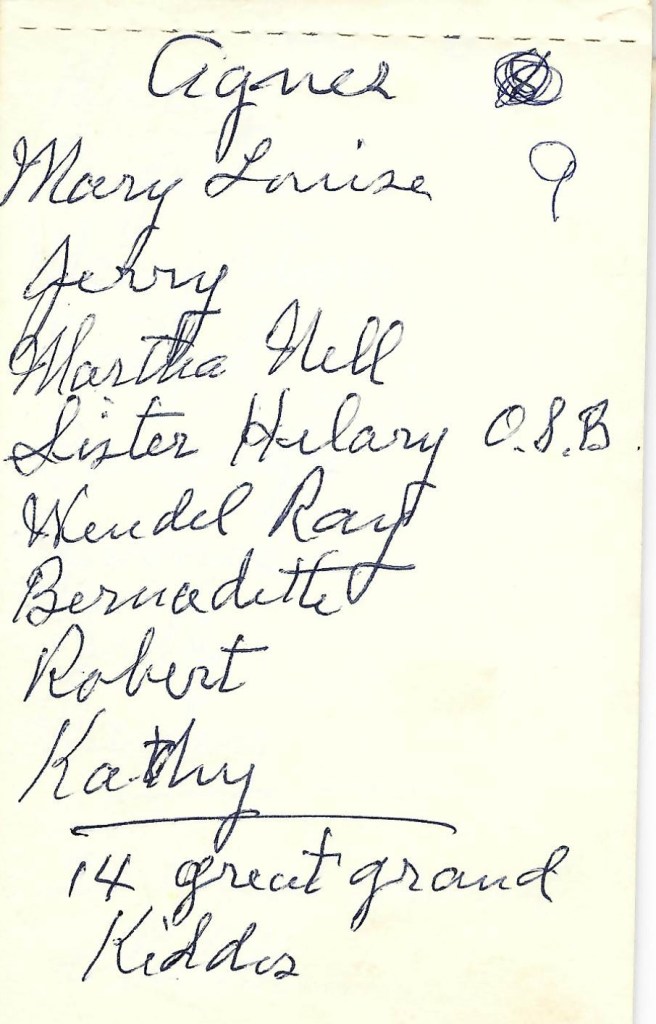

She also wrote to her daughters, more frequently Agnes, her oldest child, who lived two hundred miles away, moving the long distance some two decades before, when she and her husband looked for land that they could farm. Agnes, the eldest, was expected to keep tabs on the other seven siblings who now lived in the same area, bringing Grandma up to date on “her kids on the Plains” with her correspondence. Also, with most of her own children now grown, Agnes had the time to correspond with Grandma.

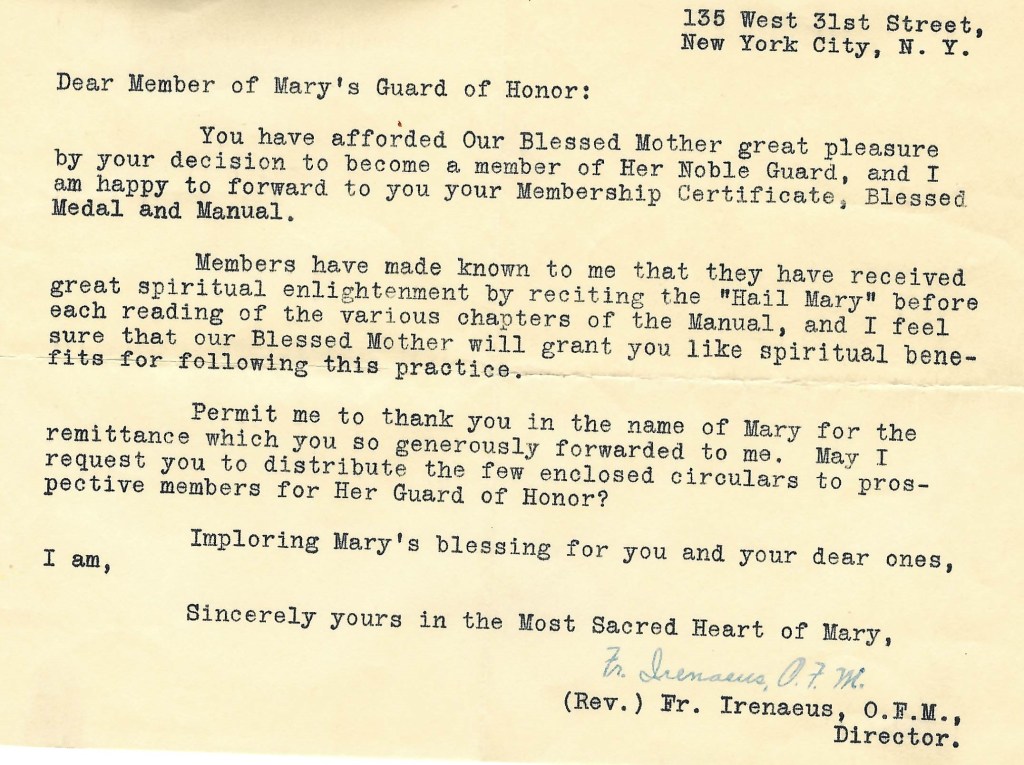

Just as often, Grandma would write letters to people outside the ordinary orbit, especially missionary priests or missionary nuns, sending them a few dollars along with a few lines. Eagerly and earnestly, I’d be deputized to put the letter in the mailbox the next morning, a big job, making sure the red flag was positioned outward so the mailman would know to stop.

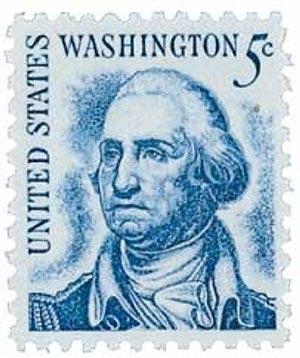

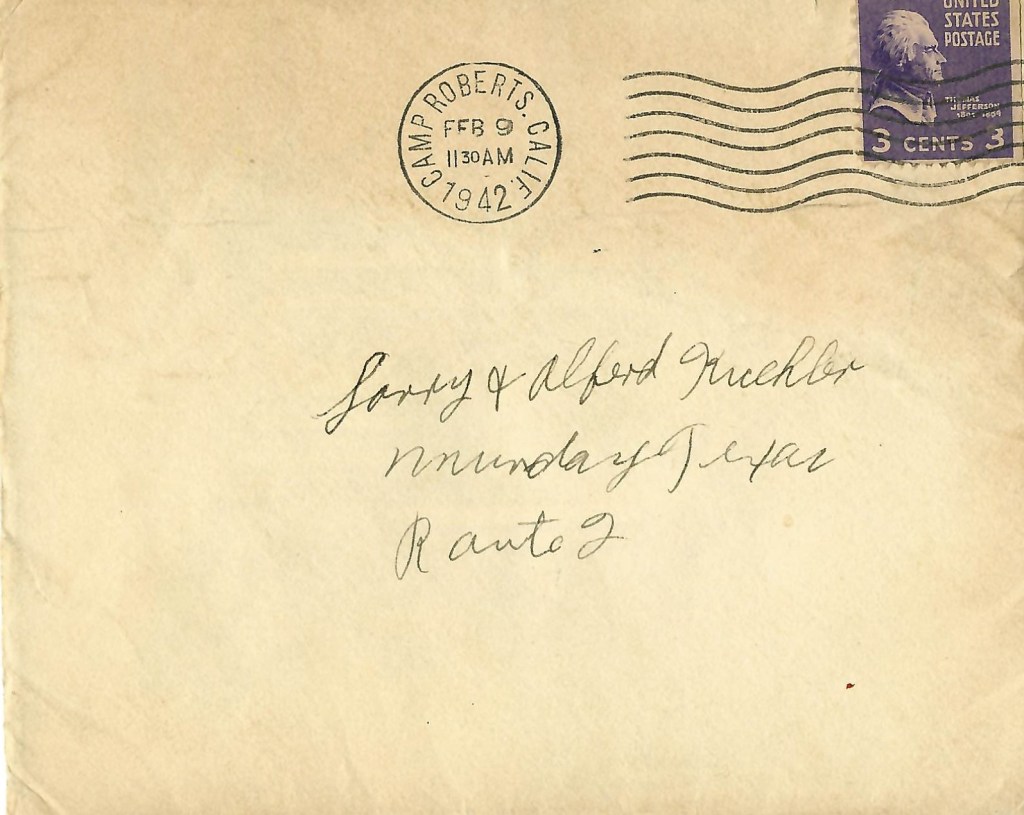

Even these many years later, I can still visualize the five-cent postage stamp I’d sometimes get to lick and put on the envelope, with George Washington’s profile on the blue background, the stamp increasing a penny in cost in 1963. Thrifty by training and someone who counted even pennies, Grandma was not happy when the stamp soared, as she saw it, to that additional cent.

Crawling through the deep and dark cavern of my memories, like a spelunker finding his way through a cave with a dim headlight, I have a faint recall of the four-cent stamp that preceded Washington’s, this earlier one with an image of Abe Lincoln on it. A few years later, in 1968, the cost of a stamp increased again, this time to six cents, two choices in images, both presidents again, FDR or Ike.

Adding insult to injury, the new stamp with FDR’s face on it didn’t set well with Grandma, whose feud with FDR went years back, its origins unknown to me since I knew next to nothing about politics, an animus that seemed disjointed because Grandma, like most of the South, voted Democrat. With a postage stamp now costing fifty-five cents, I suspect Grandma would 1) refuse to believe it; and 2) blame it on FDR. Always equalitarian, Grandma didn’t like Eleanor either.

Reflecting on the words that we still use in reference to letter writing, it is interesting that the word “pen” has its origins in the Latin word for feather, more than a coincidence since the early pens were quills, or feathers, taken from a big bird, such as a goose, with preference for feathers from the left wing. Dipped in a bottle of ink, the quill pen was the chief instrument for writing for ages, pictures of Ben Franklin sitting at a desk with a quill pen in his hand imprinted on our minds from our early school days.

Likewise, the word “to write” at first meant to cut or to inscribe, denoting the materials used–wood or stone–for writing. Even the word “paper” is a reference to its earlier form, papyrus, made from the papyrus plant and used in ancient times as a surface for writing. Sturdy and strong, ancient papyrus scrolls still exist, now fragile and fragmented for sure, the Dead Sea Scrolls found in 1946 a good example. These words we unknowingly use every day, still very much in our vocabulary, have a long history, with little change over the centuries.

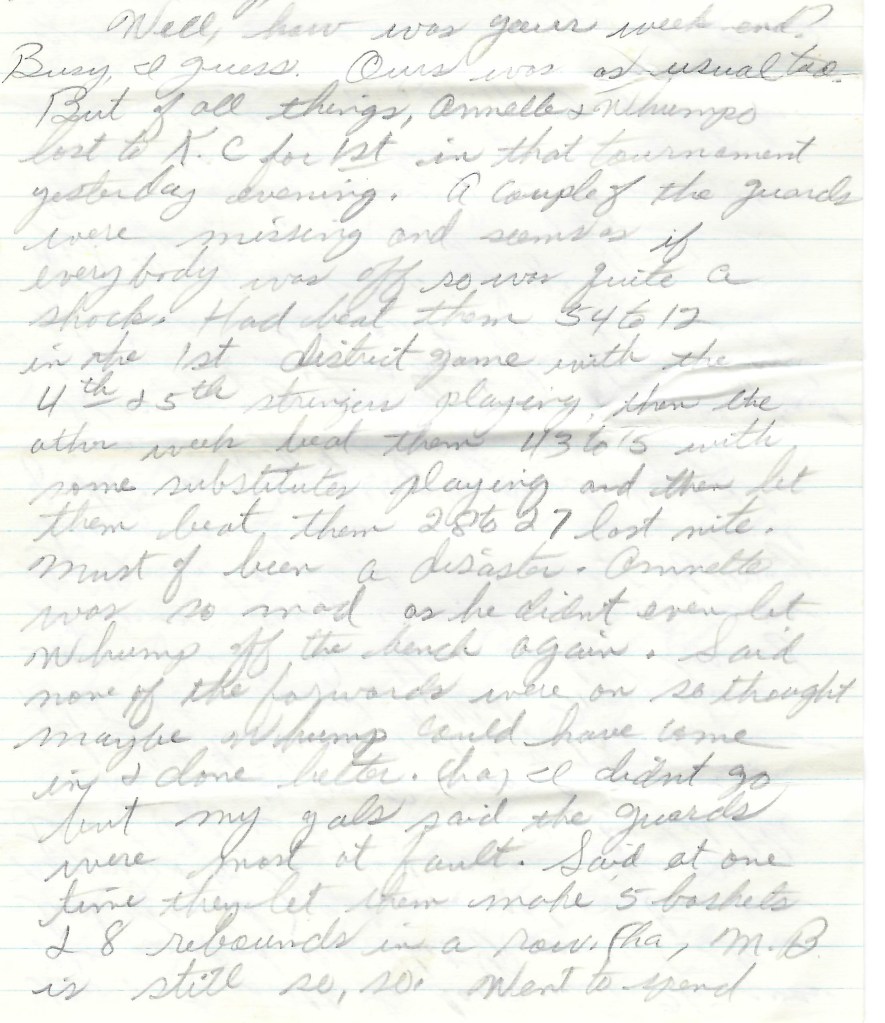

When re-reading some of Grandma’s handwritten letters–fortunately a few made it to the present day–it is clear that she stayed with the ordinary topics of her life, such as health and illness, the living and the dead, the weather and the crops, offering a verbal picture of her days and weeks, providing a visible speech to the recipient, bringing herself into the other person’s home, not by a knock on the door this time, but by a letter in the mailbox.

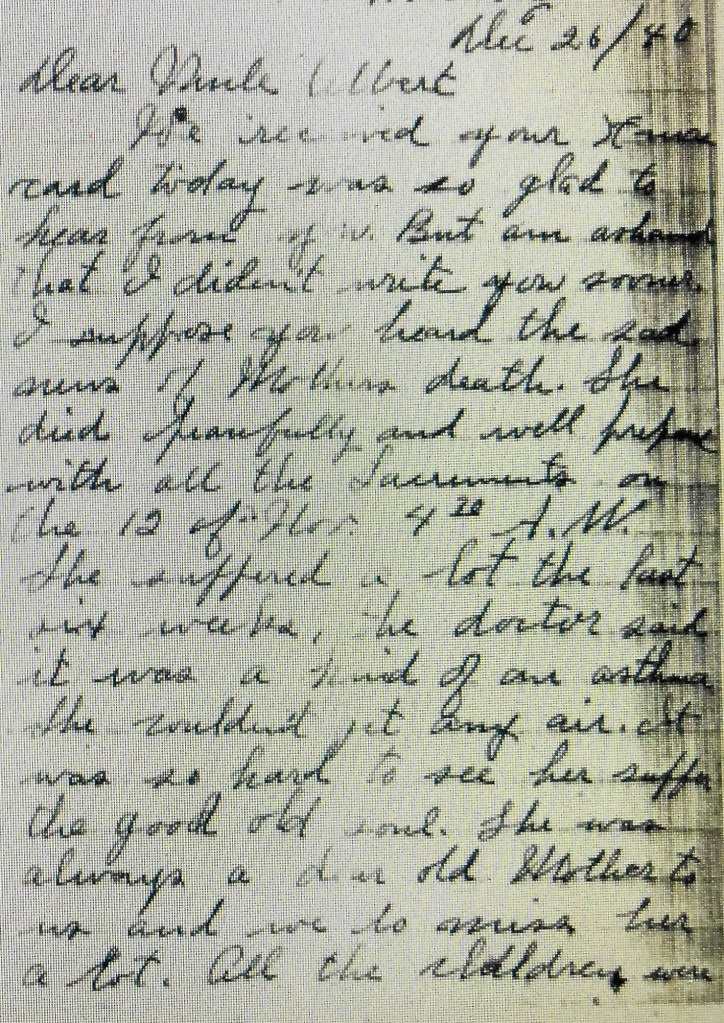

Without much knowledge of her earlier years, it is difficult for me to say with certainty when Grandma became a letter-writer, but a letter still exists that she wrote to her uncle when her mom died in 1940, the letter explaining the cause of death as well as offering apologies for the delay in communicating this event to the recipient, her mom’s brother, Albert.

One thing is certain. With two sons in World War II, Grandma became a regular letter-writer, her desk in the farmhouse put inside a closet near her bedroom that she now converted into a place to pray and to write, both serious causes as the war continued, endangering the lives of her two boys, as well as the lives of other boys from the farming community. According to my mom, Grandma spent a lot of hours in that closet, either praying or writing letters to her soldier sons, Rein and Ben.

Although Grandma’s letters were of the garden variety, as were most people’s, there are numerous examples across the ages of important letters being written by well-known historical figures, such as Paul of Tarsus, whose thirteen letters to various early church communities, Galatia, Thessalonika, Ephesus, Corinth, and Rome, to name some of them, would form the greater part of the Christian scriptures, elevating for subsequent generations, not only knowledge of Christian ways, but also the importance of writing letters.

The same can be said of early American history, with the correspondence between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson becoming, in time, a treasure trove for historians, their correspondence providing keen insight into these giant designers of our republic, also giving us a contemporaneous account of events that would shape the young democracy.

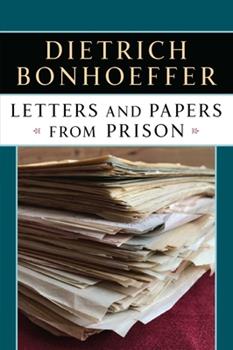

In the last century, the German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer who opposed Hitler’s ascent in Germany wrote letters during his imprisonment and prior to his death that would become a book called Letters and Papers from Prison, a similar title to the one that Martin Luther King, Jr. would write called Letters from a Birmingham Jail. These men, among others, changed the course of history with their letters, their correspondence regularly quoted, continuing to challenge people into our current century.

Even less well-known letters were welcomed in an earlier time, the new immigrants in this country always eager to hear a word from the home country, riding once a week or so into the nearest town where there was a railroad to see if a letter had arrived from family back in Germany, jubilation when a letter was there, disappointment if nothing had come, concern and worry heavy on their minds because they had received no word from home. These letters were a life-line, as vital as the maternal umbilical cord, giving strength and subsistence to newcomers in a strange land.

I have known the same feeling, having lived most of my life away from home, leaving home at the young age of fifteen, a letter received from a loved one providing that much needed and much wanted connection that distance plots to break. Hands down, Mama was a great letter-writer, perhaps learning from her own mom the importance of letter-writing, sometimes sending me two or three letters a week while I was away.

Considering she had a houseful of kids and a day full of work, it is mind-boggling that she could continue to write at such a pace, but she did, sitting at the kitchen table late at night, after the kids were in bed and the floors had been mopped, sometimes midnight before she was done, telling me with words on a page of the world I had left, keeping strong my link with those I loved.

Packed away in my trove of memorabilia, there are a number of letters that I received from my brothers and sisters, some very young, their handwriting still tentative and undisciplined, as any child’s early scribbling is, but still bringing me news via the written word. One of my favorites, still legible, in a loose sense of the word, is one of my baby sister’s letters, written to me before she could write. Somehow, even then, she knew writing a letter was something important to do and she wanted to do it, just like her older brothers and sisters did.

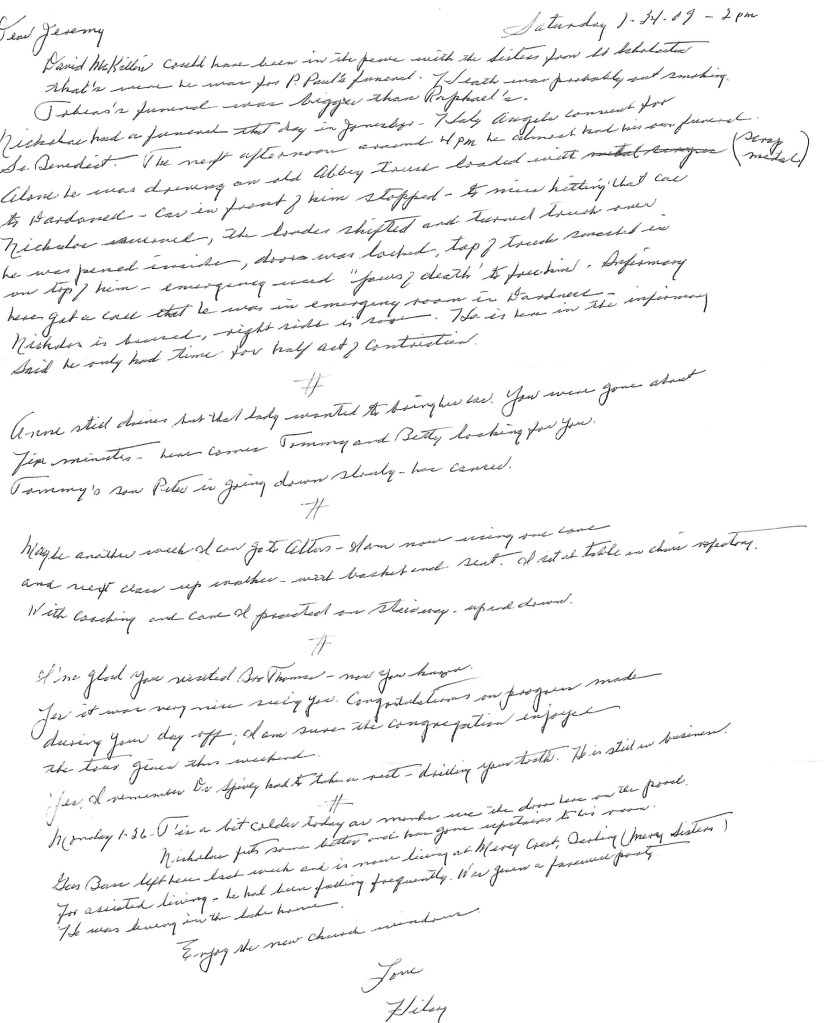

Over the years, there have been others who belong to the letter-writers hall of fame, among them an old mentor of mine who sent letters to me up until just weeks before he died, telling me of his day, of people we knew, of experiences that had come his way. His stature as a superior letter-writer is unsurpassed because I was only one of many who had the privilege of being the recipient of his letters. How he found the time to correspond with so many people is incomprehensible, except to say he found it important to stay in touch with others, investing his time in these letters because the people they were written for were important to him.

When thought about at a deeper level, when doing more than simply seeing the words on the surface of a page, a letter is always a gift, not only because it keeps alive the connection between persons, but because it takes time for a person to write a letter. Once we realize that truth and once we see that our time is the greatest gift we can give to another person, unequaled because it is a limited quantity, expended by selection, never retrievable, we gain an appreciation for any letter we receive. Put another way, the time a person gives us when writing a letter to us is time taken from someone’s life, time given to us, time never theirs again.

These days, we are people on the go and our writing shows the rush, with text messaging and emails the preferred means of writing to others, pen and paper almost obsolete in this electronic age. Texts and laptops are used much more frequently than handwriting. Studies show that up to ninety-percent of all business correspondence is now done by email.

Even college students use their laptops for taking notes in the classroom, although researchers say the new method is not as good as the old method for retention. If that were not sufficiently a sure sign of things to come, now schools no longer teach cursive writing because they deem it unnecessary, keyboarding seen as something more relevant and important to learn.

In fact, some social scientists predict that writing will be phased out by the middle of this century, an astounding prediction, with writing replaced by computers that respond to our voices. This “speech to text conversion,” as it is called, is predicted to become the primary means of communicating with others. If we find this change unimaginable, we might remember that the only place you can find a typewriter these days is on eBay.

Just as the keyboard, for all intents and purposes, has replaced handwriting, so “speech to text” will replace the keyboard. After that, perhaps we will forget how to write, allowing computers to do the work for us. While the need to read will stay, the need to write may not have as long a shelf life.

Occasionally, I still receive an old-fashioned, hand-written letter in the mail, bringing a smile to my face, reminding me of Grandma’s desk, and in that moment I find a special joy, appreciating the gift of time that I hold in my hand, knowing the letter writer had decided to take a piece of time, giving it to me graciously and generously. I am humbled by the sight of such generosity in these strokes of a pen upon the page.

–Jeremy Myers