I’ve been known to have a sweet tooth on occasion, and those who know me well know I never say no to chocolate in just about any form, although dark chocolate makes me smile less than milk chocolate does. Since others in my family share the same sweet tooth, I’ve heard it explained as something in our DNA, likely from our dad, who loved milkshakes above all else.

To have a sweet tooth, as most of us have learned, means to have a liking for sweet-tasting food, especially candy. Anthropologists like to say that having a sweet tooth goes way back in human evolution, with our biped ancestors choosing sweets because they provided high energy, something necessary when you’re always on the run from overgrown bison and humongous dinosaurs. Who would have ever thought having a bag of M&Ms might mean the difference between life and death?

It is said that our ability to taste sweets is weak, at least when compared with our ability to taste bitter things, these stronger because back in the day we needed to quickly identify deadly plants. So we fine-tuned our taste buds for bitter foods, while keeping our taste for sweets less refined, although certainly not less enjoyed. A pity it is not stronger, this taste for sweets, although our desire for sweets shows little weakness.

Imagine my curiosity, then, when billboards started popping up along Interstate 44 E outside Springfield, Missouri, each advertising a “Candy Factory” straight ahead, or, more precisely, forty-two minutes northeast of Springfield. Most of the signs had some cartoon character in red stripes, a happy-looking guy, probably meant to lure children’s attention towards him and the promise of candy, making those forty-three miles tough on parents behind the wheel, who had to answer too many times to count the quotidian travel question of children, “Are we there yet?”

Unable to resist the enticements proclaimed on the billboards, ill-prepared to say no to the possibility of counters of candy, my travel companions and I pulled into the lot of Redmon’s Candy Factory, parked the car, and walked into the most sweet-smelling, eye-popping, taste-bud exploding store you’ll ever see. The billboards had not been hyperbolic, just the opposite, this time telling the absolute truth, a candy-lover’s dream of going to heaven right there on I44 E.

It’s difficult to describe the initial assault on every sense as we stepped into the Candy Factory, assault not a bad thing in this instance, except for the fact that, like all assaults, it was overwhelming and we were under-prepared. After the olfactory, optical, and gustatory parts on us calmed down–no less easy than a kid’s excitement scaling back on Christmas morning–it became clear that the Candy Factory was more than a conglomeration of candies; it was a neatly organized beehive of sweets that would have made honey bees proud.

There was the fudge counter behind glass panels, with every imagined and unimagined type of fudge–twenty, they say–put on display, rich and thick trays of chocolate fudge dressed up with caramel or red velvet or raspberries, each one as beautiful and unblemished as debutantes at a cotillion ball in New Orleans. The sight of so much chocolate–even without obliging the sweet-voiced girl behind the polished counter who offered samples in small, fluted, muffin cups–was enough to induce a diabetic coma.

With the smell of popcorn permeating the air, letting our noses lead the way, we found ourselves before a wall full of any and every kind of popcorn, some freshly popped like you’d get in a movie theatre, but most bagged and labeled, all within arm’s reach, answering every popcorn lover’s want, however depraved.

About the same could be said of the pretzel shelves that made the ordinary pretzel feel like the unpopular kid in Middle School who wears black-framed glasses and who doesn’t have any cool video games. In other words, there were lots of cool pretzels–chocolate coated, cheese-flavored, buffalo-wing flavored, all looking like the Neiman Marcus of the pretzel world.

Taffy. Heavenly taffy. Beautiful taffy. Caramel. Cheesecake. Salt water. Take your pick from seventy different types. Take two. Maybe three. But not just taffy. Every kind of candy loaded to the brim of old-fashioned wooden apple baskets, each basket overflowing with a specific candy, luring our hands to dig deep, this human appendage like an excavator clutching in its claw savory delights.

The sounds of children laughing, shouting, begging bounced off the walls of the Candy Factory as their parents steered them down the aisles, futility in their efforts to herd these distracted sweet urchins towards the exit doors. There really wasn’t any need for signs above the stocked items. The kids knew without having to read what they wanted.

As we took in the spectacle–all of it–I thought of Sister Laura and the small tackle box that held the assortment of candy she sold at lunchtime during my early years of schooling, and how amazed and awed we were by the sight each school day. Never before her had we seen candy sold at our little country school.

With this new endeavor, Sister Laura showed herself not to be old school, like the previous nuns who had taught there, but instead she tried new things, including the sale of candy. I’m not sure if she sold the candy as a kindness or as a commercial venture. I tend to think it was kindness on her part, knowing our limited opportunity to buy candy.

She started small, with a metal tackle box–maybe it was a tool box–which could not have held much of anything, but seemed to hold lots of everything to our wide eyes, a few flat taffy bars wrapped in cellophane, lucent enough for us to see the three-colored long stripes peeking through as well as a few candy bars–maybe two or three kinds–zero, Hershey, payday. That was about it, so far as I can remember. Probably some red hots also, always a favorite with kids.

Sister Laura would sit on a low wooden bench outside the front door to the school at lunch time, opening the tacklebox of candy for the kids who had a couple nickels or a dime or at most a quarter that could be used to buy something sweet after they had eaten their sandwich from their lunchboxes packed by their moms.

Very few kids could buy a candy bar every day from Sister’s tacklebox; maybe some did. But when Mama would give us a dime to buy a piece of candy, the morning classes dragged on like a preacher’s Sunday sermon until, finally, lunchtime came and Sister Laura pulled out the tacklebox of candy. For country kids back then, I guess you could say it didn’t take much to excite us.

In time–and it wasn’t too long–she was able to up her business, retiring the tacklebox for an official Tom’s Candy display case, about four feet tall, about four shelves in it, complete with a glass door and a small lock that looked more like a toy version than a real deterrent to theft. She could have left it unlocked, so well-trained were we against stealing, our country upbringing and our child consciences never imagining such high crimes and misdemeanors, even if they included candy and chocolate.

I don’t know what happened to the display case when the school closed its doors. Like us, it moved on, and, like the times, country schools were closed, small children were shuttled on yellow school buses to the nearby town, where candy sold in a tacklebox was quaint and where a Tom’s display case was as antiquated as a top hat made from beaver pelt.

As my mind attempted to carry this side-by-side contrast of the Candy Factory and Sister Laura’s tackle box without cracking in two, I realized distance is not always measured in miles, nor are years always measured in seasons. And while we often speak of the force of a headwind, the truth is the force of a tailwind is a far stronger agent, hurling us ahead into a future we never saw coming, turning all of us into tumbleweeds thrust forward, servants of the wind.

Not that candy hasn’t been around for a long time; it has, originating in India three centuries before Alexander the Great marched into Asia, discovering, among other things, “reeds that produce honey without bees,” as the Greeks liked to call sugar cane. Since Western Europe could not grow sugar cane, it was something novel, westerners having to depend on honey if they wanted something sweet.

Much later, the Crusaders, those Europeans who marched into the Middle East with, as they saw it, a divine mandate to take back the holy land, discovered sugar again and, when returning home, began a sugar trade industry with those far-flung places, with Genoa and Venice monopolizing this lucrative market for many years.

With sugar being imported, it was costly, and was used primarily for medicinal purposes, especially for problems with digestion. Hard to believe, but candy, as such, was at first considered medicine, only later becoming a treat, usually showing up on the table of rich people. Rock candy, basically crystallized sugar, was a luxury for many centuries.

Even as a small girl, my grandmother still lived in a world where sugar was sparse and special, growing up, as she did, on the Plains of Nebraska, where sugar supplies were brought in by rail cars from the East, the transportation increasing the cost, making it something used sparingly.

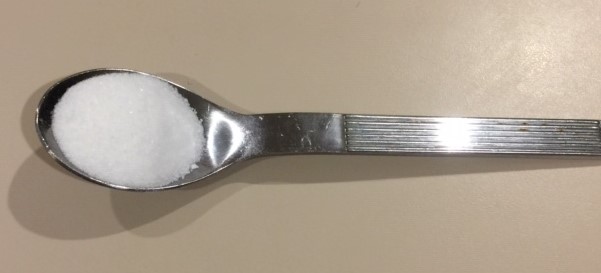

When my grandmother was a child, on Sundays her mother sometimes would fill a teaspoon for her and each of her two younger siblings, placing the spoon on a table in front of them, using the sugar as a treat to keep them occupied while she walked to and from the church several miles away. Try to imagine a child being mesmerized by a spoon of sugar today.

My grandmother would not have been able to concoct in her mind anything like the Candy Factory and, had she lived to see it, she surely would have thought the world was going to hell in a handbasket, or, in this instance, in a candy basket, our excess and extravagance evident in every bite of candy. Growing up with less, she never saw having more as a virtue.

Even when she had grown old, she only bought candy at Christmas time, buying a bag or two of what is now sold as “old fashioned Christmas candy.” I can still see the smile on her face as she sucked on one of the hard candy pieces, even then limiting the number she took, savoring each piece as if it were that spoon of sugar she had licked so slowly those Sunday mornings when she was just a little girl in Nebraska.

Almost entirely forgotten now, except for historians, it is a sad backstory to sugar that it is irrevocably intertwined with slavery. The Portuguese explorers in the 15th century bought and put slaves to work in the sugar mills that they had built on islands off the coast of Africa. The next four hundred years would see this sugar production–at the hands of slaves–increase exponentially.

So much so that historians maintain that 90 percent of the 12 million African men, women, and children who would board European slave ships during this period were on their way to sugar plantations, now found throughout the Caribbean in the 16th century, the plantation owners having replaced tobacco with this more lucrative crop of sugar cane. Nobody’s hands were clean. Both Spanish and English explorers and entrepreneurs simply expanded the sugar trade the Portuguese had set up.

If there is to be found some small bit of karma in this Columbian exchange, as historians like to call this transfer of plants and products from the New World to the Old World, it is that Western Europeans, as a rule, did not experience tooth decay until this mass import of sugar from the tropics made it a staple instead of just a rarity. Prior to sugar coming to Europe, only one in five Europeans had tooth decay. After the wide-spread arrival of sugar on those shores, nine out of ten experienced rotten teeth.

As most of us know from personal experience, even today, dentists make their living from our sweet tooth and–all their cautions to the contrary–we continue to indulge in sugar in its many shapes and sizes, the Candy Factory both a child’s dream and a dentist’s nightmare. Based on the popularity of the Candy Factory as we strolled through its many aisles the other week, our sweet tooth is nowhere near sated, even at the cost of a tortuous stay in the dentist’s chair.

We walked away from the Candy Factory with a few items, including a pecan roll, a piece of fudge, and a box of Sugar Babies, those bite-sized caramel jelly beans that are probably as much pure sugar as they are pure delight. First made in 1935, they’re making a comeback, as you may know, called “retro candy” these days, along with Sugar Daddy candy bars, which–if you’re really in the mood–come in a one-pound giant size bar, something never imagined back in 1925 when they hit the market.

In many ways, the Candy Factory is quintessential Americana, simultaneously depicting our virtues and our vices, highlighting our expansiveness as well as our extravagance, the daring and the danger of having no limits. So, if you are ever near those parts of Missouri, make it a stop. As you will see, the candy selection is astounding and, by the way, the bathrooms are the cleanest you’ll ever find, just as the billboards promise.

–Jeremy Myers