“Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” He said to him, “You shall love the Lord, your God, with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the greatest and the first commandment. The second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” (Matthew 22.36-39)

Once, a pagan approached Rabbi Shammai, a learned scholar of the Torah who lived in the 1st century of the Common Era, and said to him, “Convert me to Judaism on the condition that you can teach me the whole Torah while I am standing on one foot.” With a rod in his hand, Rabbi Shammai angrily threw him out.

Then the man went to Rabbi Hillel, a contemporary of Rabbi Shammai and an equally brilliant scholar, saying to him much the same thing, “Convert me to Judaism on the condition that you can teach me the whole Torah while I am standing on one foot.” Rabbi Hillel, it is said, converted him, teaching him the following, “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor. This is the whole Torah. All the rest is commentary.”

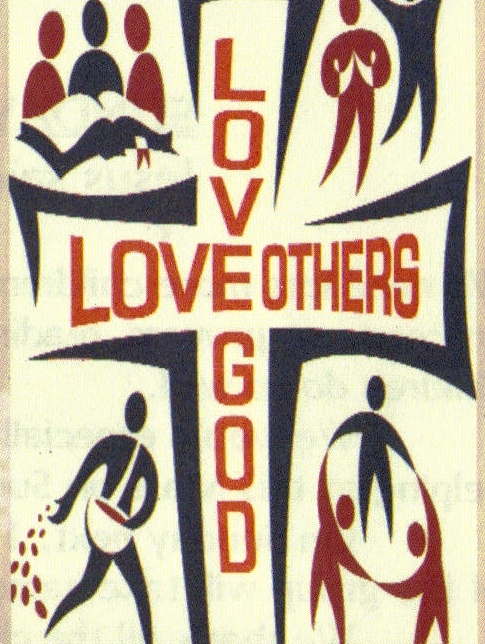

Today, as our text makes clear to us, another person–a scholar of the law–approaches the Rabbi of Galilee with a similar question, “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest,” his question also seeking a summation of all Jewish teaching. The Galilean Rabbi promptly provides a response to the scholar, bringing together into a dual commandment the whole law and the prophets.

“You shall love the Lord, your God, with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind. This,” he said to the scholar, “is the greatest and the first commandment.” Then, surprising the scholar, he adds something more. “The second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” connecting two commandments, making them one, inseparable and intertwined forever after.

With that response to the scholar, the Teacher gleaned the whole of the Hebrew sacred writings into a singular prescription, collapsing the 613 commandments contained therein into one comprehensive command, a prescription of love, not only of God, but also of neighbor, the two conjoined in such a way that love of God never again could be divorced from love of others.

And by stating that this was the greatest commandment, which is to say it is the widest one, all the others subsidiary to this great one, the Teacher implies that complying with the lesser commands, while failing at the greater one, means one has failed to live the Torah, for the Most High God wants one thing from his people, that they love others in the same way he has loved them.

As later history would show, the early followers of the Crucified Galilean understood the primacy of this precept, making it the guiding principle of their lives, never allowing lesser obligations to replace this overarching commandment, but always subsuming them under the commandment of love of God and neighbor. To fail at love, they understood, meant to fail at discipleship, even if they did a good many other things right.

Already in the early second century, an Athenian philosopher named Aristides defended the followers of the Galilean Teacher in a letter addressed to the Emperor Hadrian in Rome, describing for him these ardent disciples in this way, “Christians love one another. They never fail to help widows. They save orphans from those who would hurt them. If one of them has something, he gives freely to the one who has nothing without boasting.”

He continues his description with these words, “If they see a stranger, Christians take him home and are happy as though he were a real brother. They don’t consider themselves brothers in the usual sense, but brothers instead through the Spirit of God. And if they hear that one of them is in jail or persecuted for professing the name of their redeemer, they all give him what he needs and, if it is possible to redeem him, they set him free.”

Then, concluding his case, he states, “And if there is among them any poor or naked and if they have no spare food, they fast two or three days in order to supply the needy. They live with much care, justly and soberly as the Lord their God commanded, and they do not declare in the ears of the multitude the kind deeds they do but are careful that no one should take notice of them. Truly,” he said, “this is a new people and there is something divine in them.”

Truly, this is a new people and there is something divine in them. This ancient testimony attests to the fidelity of the followers of the Crucified Galilean, showing them to love others actively, particularly, even when such love is personally painful, as it is because such love always brings privation, personal costs, and problems. It is, in other words, imitative of the love of God, who loves his creation actively, particularly, and passionately, as understood from its Latin root, pati, meaning to suffer.

Firstly, to say love is active is to say it acts, doing something concrete, the opposite of passive, which does nothing, but watches from a safe distance. Love, as an active agent, addresses the needs of others, seeks answers to problems, and provides the solutions. Rather than saying, “I can’t,” love always says, “I can.”

Augustine of Hippo described active love, writing in the fourth century these words to the members of his church in North Africa, “Love has hands to help others. It has feet to hasten to the poor and needy. It has eyes to see misery and want. It has ears to hear the sighs and sorrows of others. That,” he said, “is what love looks like,” his words reminding us that the Galilean’s command to love is not theoretical, but is practical in every way.

Secondly, to say love is particular is to say it loves the person in front of us, more so than the anonymous populace whose faces we never see or whose cries we never hear, an easier and safer love because we never come into contact with these persons. Love, when it is real, is not long-distance, but is here and now.

The Russian writer, Dostoevsky, has one of the characters in his book,The Brothers Karamazov, offer this confession, “The more I love humanity in general, the less I love man in particular,” a confession each of us could make, since we too often say we love everyone while failing to give to the hungry person who stands before us, or failing to clothe the naked person who passes our path, or failing to welcome the stranger who knocks on our door. But loving others in general, always a temptation because it is easier and simpler, is not the same thing as loving another person in particular, never easy and never simple.

Hence, the third proof of love, its being passionate or entailing suffering, a reminder that true love is difficult and costly; if real, it does not come cheap, the cross that the Galilean suffered upon always the exemplar of the self-sacrifice that is an inherent part of genuine love of another, the outpouring of Divine Love as sweat and blood poured from his body now the means by which we measure our own love for others.

Truthfully, that divine template of love becomes a frightening and a forbidding measure for people who like to play it safe and who run for the exit doors when the going gets tough. Convincing ourselves that love should come easy, a conviction that has become a commandment for our times, we eschew the challenges that are an intrinsic part of love, choosing self-satisfaction over self-sacrifice.

When we accept that love is difficult, then we are able to move from illusion to reality, removing our clean and pressed clothes free of dirt and grim, putting on our work clothes full of tears and spots. Or as the writer Madeleine L’Engle once said, “The best way to help the world is to start by loving each other, not blandly, blindly, but realistically, with understanding and forbearance and forgiveness. In my view,” she said, “realistic love means to see things as Jesus sees them and love what is there, not what we choose.”

And what is there, needing our love, as experience teaches us, is the recalcitrant child that is always in trouble, the obnoxious neighbor that makes our life difficult, or the homeless man outside the store with the sign that reads, “Need Food,” each person asking more than we have to give, each time testing the limits of our love, each response turning the command to love into a real-life experience. “We have to love our crooked neighbor with our crooked heart,” the poet W.H. Auden reminds us.

When the Galilean Teacher answered the scholar of the law, telling him that the greatest of all commandments was to love God and to love neighbor, an answer that stitched together two ancient Hebrew commandments, now no longer separated, he made it clear that if we love God’s people actively, particularly, and passionately, then we are at the same time loving God, whose love for his people also is active, particular, and passionate.

As we look around our world, we can only say we have fallen short of the command to love as the Rabbi told us we are to do, not following in the footsteps of his early followers who made the commandment a way of life, not an ideal put on a dusty shelf, as we so often do. Decades ago, Archbishop Romero came to much the same conclusion, telling his people, “This is the greatest disease of our world today–not knowing how to love.”

He told them, “Everything is selfishness. Everything is exploitation of human beings. Everything is cruelty and torture. Everything is violence and repression.” And as we know, a short while later, he was shot to death by soldiers of the state, his bullet-ridden and blood-stained body proving how far we have fallen from the commandment to love others.

Today, the words of the Galilean are a call to become better than we are, a command to imitate the love of God, and a challenge to recreate the world into the place it was in the beginning. The possibility, if not the promise, persists. As the Jesuit philosopher Teilhard de Chardin once wrote, “Someday, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of love. And then,” he wrote, “for the second time in the history of the world, man will have discovered fire.”

–-Jeremy Myers