August is the cruelest of months. Of course, I borrow from T.S. Eliot, who claimed April was the cruelest of months, a claim I can’t possibly understand, unless he didn’t like the idea of hope. As I recall, he made the statement in his poem, “The Wasteland,” the title itself suggesting he didn’t hold much hope for the world.

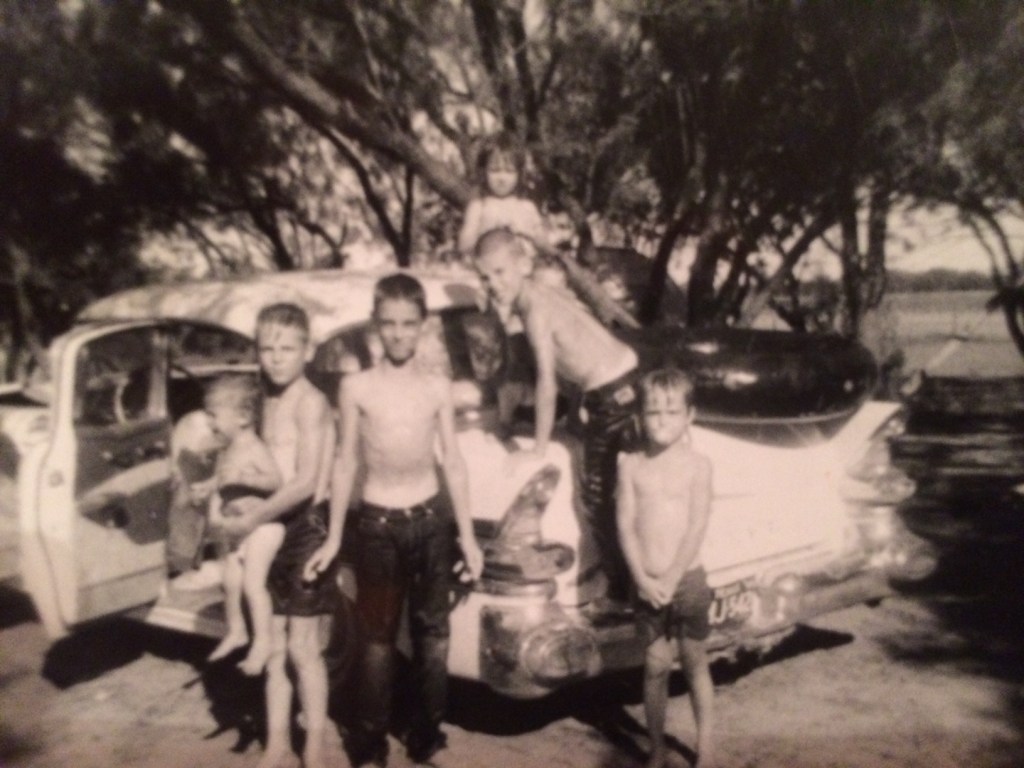

As a boy, August was so hot we shucked our t-shirts and lost our shoes, choosing to stay cool in these ways, our skin turning dark and our feet becoming calloused, minimizing the laundry our mom had to do, while avoiding the few asphalt-covered roads that had turned liquidity under the August sun, which could blister even calloused feet.

Much like the family dog–Tiger–my brothers and I tried to find things to do in the shade. Climbing trees was an option, but West Texas and trees generally don’t co-exist, so there were only a few branches in a peach tree or two that we could climb. We did a lot of walking on dusty roads, no particular destination in mind, just checking out the little community in which we lived, much as Tom Sawyer did, who also tried to turn hot summer days into an adventure, resistant though they might be.

Our mom, blessed with an easy-going disposition–thank God–didn’t mind our running up and down the sprinkler hose that she used to water the quickly browning Bermuda grass, our little feet turning the ground into a mud hole, not giving the grass underfoot a chance to live, much less green up. Within minutes of her starting up the long, green, sprinkler hose, we’d subvert its purpose, using it to cool us down instead of to green up the grass.

Recently, I’ve watched my nephew’s dog do the same thing, and I swear I can hear the dog laughing out loud as he shakes the water off his back, pretty much the same as we did many years ago, except we had burr haircuts, unlike his shaggy hair. As a rule, my brothers and I didn’t get into too many quarrels over the water hose, but took turns racing down the sprinkler, the spray of water making us as happy as newly baptized heathens.

Of course, the circumstances lent themselves to a slip-and-slide game, not the fancy kind with a plastic slide and high walls that Amazon sells these days for over a hundred dollars, but the original kind, with mud being the slide, our bodies caked after a while, turning us into Australian aborigines. Since our jeans were cumbersome in the mud, we usually shucked them, pretty much ruining our tighty-whities, but–again–our mother said little, our briefs now brown long before colored underwear became popular.

As the days of August sluggishly moved along, our mom would have to move the sprinkler from one place in the yard to another spot in an effort to save the grass, although we soon enough turned the new location into a like mud hole as we had done with the last place. I’m not sure we really had much of a lawn during those boyhood summers. But she didn’t mind. She was more interested in growing boys than in growing grass.

When we got a few more years on our backs, but before we were old enough to be capable of any kind of work, we would walk to the banks of the Brazos River, about a mile away, hopeful that there might be a trickle of water in the river bottom to cool us off. Rarely did we find anything that looked like a river there, more generally a shallow hole of water here and there in which we could sit and soak, chatting away underneath the scorching sun, watching the mud swallows build their nests beneath the bridge far overhead.

Hamlin Garland, the author of Boy Life on the Prairie, among others, says he and his friends would do the same thing in their little Iowa community in the 1870’s, except in this instance, the Maple River was four miles away, making for more of an excursion than our lesser journey.

As he tells the story, “The boys usually went in parties of five or six. Sometimes they started late on Saturday afternoon, more often on Sunday; for many of the parents took the view that cleanliness was next to godliness, and made no objection to such Sabbath excursions.”

As he tells it, later, with the river finally in sight, the boys would become very excited at the first glimpse of the water. He writes, “When the river came in sight, a race began, to see who should first throw off his clothing and be as the frogs are.” Apparently, some things didn’t change in a hundred years, because we also would on occasion “be as the frogs are,” in this way sparing our mom from trying to get the red mud out of our white briefs.

Walking back home from the river was, of course, less fun, now sporting sunburned skin, a layer of sand coating our small bodies, and having to walk on the side of the road, since the asphalt was insufferable on our bare feet. I could be wrong, but I don’t remember a single summer day that we wore shoes, except for Sunday morning when we went to church. Later, when flip-flops were an option, we still walked bare-footed.

Some relief would come with a summer thunderstorm, but these were few and far between, most August days dry and dusty, a miniature dirt cloud blowing across the road much more likely to happen than a genuine rain cloud. Yet, when it happened, a cloud opening up and rain pouring down, we’d run in the rain, faces turned towards the skies, rejoicing like the Hebrews in old Elijah’s day when the skies did not open for three and a half years. We’d walk back into the house soaked to the skin, shedding our wet clothes like a snake sheds its old skin.

If it really rained–and that was not likely–but when it did, the bar ditches that formed grids within the community would fill up with water, small canals now flowing towards the Brazos, with previously comatose frogs now freshly revived and croaking songs to the high heavens.

We’d join the frogs in the bar ditches–there was room for all of us–letting the flow of water float us for a quarter of a mile, sometimes more. Once in a while, we’d suffer a cut on our foot, somebody having previously thrown a soda pop bottle in the ditch, our feet making contact with it in the mud. But the pain was a small price to pay for the hours of fun we had.

When we were much bigger, we’d hype the game up, grabbing inner tubes from our dad’s shop, using them both as life jackets and floating devices, riding the surge almost to the point where it emptied into the river. But this sport came years later, when we had more sense, believing our navigational skills on these inner tubes in the narrow ditches like those of an old-time pilot of a steamboat on the wide Mississippi.

In the heat of the summer, when dogs couldn’t even find a shady place, our mom would load us into a car and carry us to a place known to locals as “Mansfield Park,” the place nothing like a park in the modern sense of the word, not a bit of green anywhere in sight–except on the mesquite trees–but still called a park, I guess, because it was a fun place to go.

Named after the man who owned it, Mr. Mansfield, an old (or he seemed so at the time), bespectacled man with a pouchy belly, always dressed in blue-striped overalls, it was really a small area with a few mesquite trees and several tanks, not the military kind, but man-made watering holes where a boy could cool off on a hot summer day.

The primary purpose of these stock tanks, or ponds, was to provide water for cattle, and so were typically found in pastures where cattle were fenced in with barbed wire strung on old tree posts put in the ground. I’m assuming these tanks served the same purpose at one time on Mr. Mansfield’s property, although there were no cattle in sight when we went there.

By the time we came along, he’d spent some years clearing the area of dead tree branches and buffalo grass, building some picnic tables in the shade of the mesquite trees, and allowing locals to come onto his property to swim in one of the tanks. He’d even built a small wooden barge that could be pulled across the smaller tank by using a large cable that crossed from one bank to the other. He had constructed a bench in the middle of the barge, making for a comfortable ride across the tank. although it took the strength of Hercules for little boys to pull the barge from one side to the other side.

With each year, Mr. Mansfield would add one or two things to make the park more like a playground, including a giant barrel built that kids could make turn like an old mill wheel, turned this time by running feet, not water. He also put up a swing set or two, slides that went into the water, even a little bridge that crossed over a slight ravine, connecting one play area with the swimming area. For boys used to lawn sprinklers and mud holes and dry river bottoms, it was a giant step up.

We didn’t spend much time fishing, but for those interested in it, Mr. Mansfield had a another tank nearby, a larger one, supposedly filled with fish, although I don’t recall ever seeing anybody get a big or, for that matter, a small catch from it, but surely that is a lag in my memory, and not a verifiable fact. Still, I recollect no genuine fishermen stories ever told. For little children, the man had made a shallow pool out of concrete, maybe a foot deep, maybe a little more, but not much more.

Mansfield Park was about seven miles or so from home, which meant the drive there was exasperatingly slow, our patience wearing thin with each mile, the hot August air blowing through the open windows of the car, taunting us with its heat, as we waited to wade in the water at the park.

A dirt road took us to the front of his house, about a half-mile from the main road, where Mr. Mansfield charged each car $1 per person to go into his “park.” We’d wait until he saw us through his front window, coming out his screened door, a smile on his wrinkled face. Seeing the car full of children that Mama always had in her vehicle, several small heads hanging out of each open window, he’d quit counting and just give her a discount. He was a kind man in every way.

After paying, we’d follow the dirt around a bend or two until it opened into the “park,” the doors of the car flying open, our feet hitting the ground before Mama could really bring the car to a full stop. The smaller children would swim in the kiddie pool, while the older ones would wade into the stock tank, but never too far because we weren’t good swimmers. That achievement only comes to those who live around a body of water, a rarity, as I said, in West Texas.

Mama always made these trips to Mansfield Park a special event for us, far beyond just the opportunity to play in the water on a hot August day, even if the water never cooled down because of the heat of the sun, which warmed it like heat lamps on a Luby’s serving line. Still, it didn’t matter to us, so long as it was wet, although we often walked away looking like lobsters after a day in the sun.

Mama always liked to think of it as a picnic–and it was–so she would spend the morning frying chicken and fixing potato salad and opening cans of pork and beans, putting all the food in a cardboard box in the trunk of the car, along with large containers of sweet tea. After playing in the water, we’d sit at one of the tables under the pavilion or on the ground beneath one of the mesquite trees, enjoying the fried chicken and iced tea.

Since we didn’t get to go regularly to Mansfield Park, maybe two or three times each summer, it stayed special, and, while we were there, we enjoyed it fully, our only complaint coming when it was time to leave, although Mama never rushed our stay there. She seemed to enjoy it as much as we did, her joy coming from seeing us so happy, being always the giving and loving mom that she was.

As you might expect, there was a city pool in the neighboring town, about seven miles away, but we never went there when we were growing up. It was for the city kids and, costing a quarter per person, it was an unnecessary expense, not to mention the cost of the candy bars or soft drinks at the snack bar. To us, the city pool was filled with strange faces, loud splashes, and a showoff or two.

In later years, when there were fewer children at home, the younger ones would go to the city pool, but it was a rarity for us older kids. The few times I went I always felt out of place, everything unfamiliar, the water too blue, too cold, too clean, the kids in store-bought swimming suits, a lifeguard sitting high in a chair, shouting reprimands down like an angry god. Growing up as a country boy, I found the city pool too citified for me, everything concrete, chlorined, and cold.

Today, one of my sisters has a swimming pool at her home, a really beautiful pool that a later generation of grandchildren can now fully enjoy during the hot August days. She also keeps a large cooler filled with drinks and snacks for them. It is a long way from Mansfield Park, and not only in miles.

Sometime in the 1980’s, Mansfield Park closed. Mr. Mansfield grew too old to care for it, some wild groups began to show up there, and an accident or two occurred, turning it from a fun place into a liability. I am sure it broke Mr. Mansfield’s heart when he had to stop letting cars enter his park. He died sometime later, his park now empty of excited children, silent except for the breeze moving through the limbs of the mesquite trees. These days, cattle again graze the area, using the stock tanks as they were first intended.

On a hot Sunday afternoon not too long ago, my brother and I made a return trip to Mansfield Park, not to swim, as we did long ago, not to eat Mama’s fried chicken–she’s gone now also–but to see what remained of our boyhood recreational center. There are fewer mesquite trees now, the sun seemed hotter than before, and only the railroad posts still stand where the pavilions were.

The slide is rusty and the swing set is without swings. The barge isn’t in the pond anymore, although the cable where the slip slide went across the stock tank still swings lazily in the air, when there is a breeze. Two of the tanks are bone dry, which says we need rain. We walked around the premises, on the lookout for rattlesnakes, since the place belongs now to them, and not to us. As elsewhere in the world, little is the same in Mansfield Park, little the way we remembered it when we went there as kids.

Now, as the thermometer shows 104 degrees and I sit in my air-conditioned office, I let my mind wander back to those summer days of my childhood, when the world was simpler, when a bunch of boys walked on bare feet to the Brazos River, the dirt and pebbles hot under our feet, sweat coating our bodies like morning dew on grass, our eager eyes set on the river ahead, a place full of promise, as everything is in a boy’s life, with hours to spend sloshing, splashing and swimming in the dirty red water of the Brazos. And I think to myself that the month of August, for some reason, was bearable back then.

–Jeremy Myers