When my mother was some months old, she wasn’t gaining weight as my grandmother thought she should, so she took her to a chiropractor, who did some adjustments on her little body. Soon after, she began to put on weight, which made my grandmother happy, but my mom always blamed the chiropractor for setting her on the path to weight gain throughout her life.

When my mother was a toddler, old enough to walk around and get underfoot, she watched as her dad and other men built a new barn on their farm, when somehow a pile of lumber fell atop her, causing everyone a good fright, but she walked away from it with just a few scrapes and bruises, thanks owed to a guardian angel or two.

When my mother was three years old, she received a Shirley Temple doll from her godmother, a beautifully dressed doll that my grandmother put on a high shelf, telling my mother she could play with it when she was older, my mom pulling a chair beneath it to get a closer look at it, her little girl eyes dazzled by the beautiful doll on the shelf.

When my mother was four years old, she would stand at her mother’s rocking chair, asking her mom if she would have some more babies so that she could have a playmate or two, not understanding yet that fifty-year-old women did not have more babies, their baby-making years now behind them.

When my mother was five years old, she and her brother buried the small strap that my grandmother used to paddle them when they got into trouble, the two of them grabbing a little spoon out of the kitchen drawer, using it to bury the strap in the backyard where it couldn’t be found, never confessing its whereabouts.

When my mother was seven years old, she watched out her second-grade school window as the funeral procession took her grandmother’s body to the cemetery, crying as she remembered her sweet grandmother who always was kind to her, gifting her with her first prayer book, as soon as she was able to read the words on the small pages.

When my mother was eight years old, she and her older brothers would go ice-skating on a little pond on their farm, her brothers sending her out onto the ice ahead of them, checking to see if it was thick enough to support her without cracking, then getting on it themselves now that it had been tested for safety.

When my mother was nine years old, she and her brothers walked from school each afternoon, as they would do every year, two miles down a country road, making their way home in time to do the chores before the day was done, doing her homework later in the evening by the light of a kerosene lantern.

When my mother was ten years old, she slipped on a cement step at school, falling on her elbow, her mother taking her to the doctor after school was over, learning that her arm was broken, so she would have to wear a cast on it for three weeks.

When my mother was twelve years old, she made a swing for herself in a tree in the front yard, near the farmhouse, looping a rope over a limb, swinging from the other end in the quiet of a Sunday afternoon.

When my mother was thirteen years old, she assumed much of the responsibility for cooking the family meals, never forgetting the time relatives were visiting and her gravy didn’t turn out the way she wanted.

When my mother was a week shy of her fourteen birthday, she wrote her autobiography, a classroom exercise, expressing her plans for the future, admitting they were not definite, but stating she would like to be an artist, maybe just a fanciful idea at that age, maybe a real desire for later, but life took her on a different path

When my mother was fourteen years old, she joined her brothers in the cotton fields, during the summer months chopping the weeds out of the long rows, during the fall months picking the cotton off the dried stalks, putting the cotton bolls into a special sack her mother had sewed for her, smaller than her brother’s, at least at the start, her hands red and raw from the rough bolls.

When my mother was seventeen years old, she was valedictorian of her class, three girls and one boy making up the full class in the small country school, a happy memory, and one she liked to share with her children over the years, perhaps motivating them to academic achievement.

When my mother was eighteen years old, she went on a date with a local guy or two, but had more fun going out with a group of friends, a special outing when they could go to the swimming pool in a town thirty miles away, quite a change from a dip into a farm tank or floating on a small current in the nearby river, after a rain had put some water within its dry banks.

When my mother was twenty years old, she married the man who would be her husband for the next fifty-six years, a guy from a town sixteen miles away, whose dare-deviled driving never impressed her dad, but whose persistence won her heart.

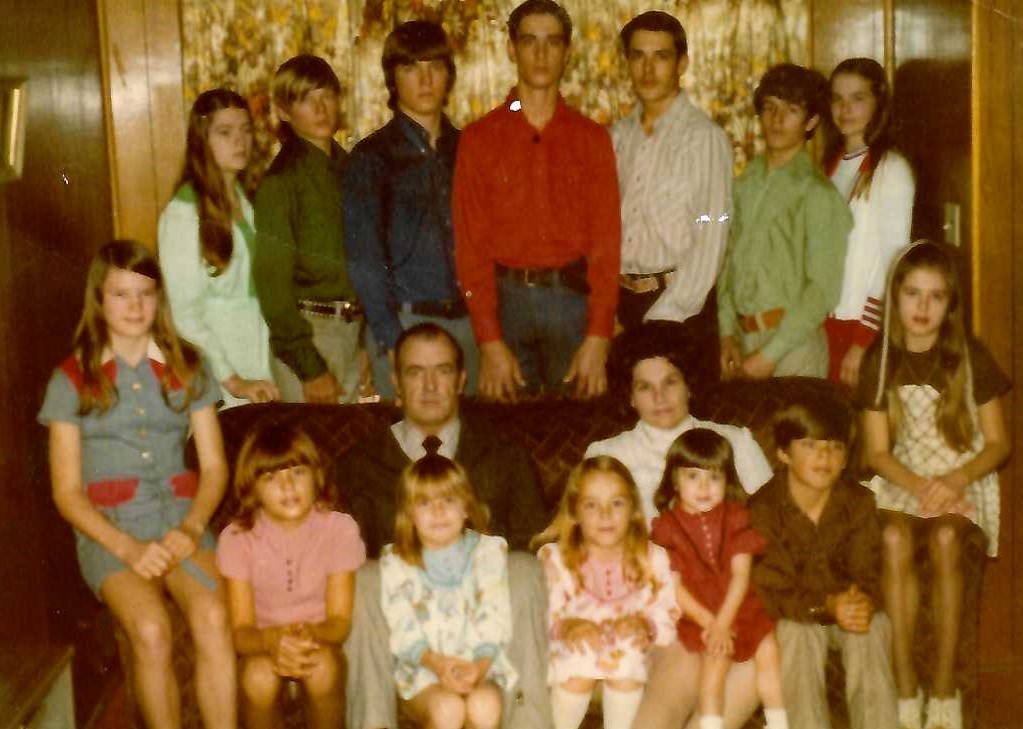

When my mother was twenty-one years old, she had her first baby, a big boy, the delivery a difficult one, but whatever pain she suffered being worth the joy of holding that baby boy in her arms for the first time, big brown eyes looking up at her, a head full of dark hair, the first of fourteen babies she would hold in her arms over the next seventeen years, each one special, each one she called a gift from God.

When my mother was twenty-five years old, she lost her dad, only seventy-two years old, a man she adored, a quiet man, a man of peace, a simple farmer, a family picture taken after the funeral vividly showing how he was already missed, not only in the picture, but in each one of his children’s hearts, the man who had always there for them, but not there anymore.

When my mother was twenty-nine years old, she learned that her second son had intellectual and developmental disabilities, a difficult day when the diagnosis was done, but she still shopped for Christmas gifts for all her children on her way back from the doctor’s appointment, with Christmas just a few days away, always accepting that life goes on, that there are good days and bad days.

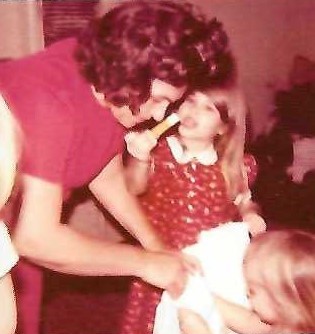

When my mother was thirty years old, she would take her oldest son on bird hunting adventures on cold winter nights, his little BB gun held in his arms, her pointing out to him the sparrows asleep on high line wires or on top of a nearby building, letting him take aim, teaching him how to shoot birds, as her brothers had taught her.

When my mother was thirty-one years old, she cooked three meals behind her gas stove every day for her growing family, sometimes taking chickens from the coop to fry, sometimes shucking corn ears from the garden, sometimes picking up potatoes left in the fields after the pickers had finished, always having food on the table, even if there were not enough chairs for everybody to sit at the table, choosing to stand while she ate at the kitchen cabinet.

When my mother was thirty-seven years old, she received a mother’s ring, each of her thirteen children’s birthstone on it, fourteen prongs holding two rows of tiny stones, thirteen for her children, the fourteenth for her husband, the largest number of settings on a mother’s ring that the jeweler had ever made.

When my mother was thirty-eight years old, the doctor told her not to have any more babies for health reasons, but she had one more, a perfect little girl born with no difficulties, proving doctors don’t always get it right, the girl born on September, a few days after her daddy’s birthday, taking his stone on the mother’s ring and stealing his heart from day one.

When my mother was thirty-nine years old, she buried her mother, their bond always unbreakable through the years, a mother she cared for in her final years of infirmity, a mother she turned to for advice, a mother she imitated in generosity, in goodness, and in geniality, now at rest in her grave, a place she visited each evening for the next four decades and more, so long as she had legs to walk on.

When my mother was forty years old, she began to watch from the stands in the stadium as her girls raced around the school track, fast as gazelles, a sport she loved to watch, enthusiastically cheering each of them on, awards accumulating for them with each year, a proud smile on a mother’s face each time one of them won.

When my mother was forty-three years old, she became a grandmother, her first grandchild choosing the moniker “Dotmama” because he heard so many people call her either “Dot” or “Mama,” deciding the combination of names suited her best, his decision changing her name forever after into “Dotmama,” called that by family and friends, by locals and long distance people.

When my mother was forty-five years old, she began work in a sewing factory, her paycheck helping to bring in money for the family, leaving early in the morning, coming back late in the afternoon, never claiming to know much about sewing, but working as an inspector, a good eye for possible flaws, a job she would hold for several years.

When my mother was fifty years old, she worked as a secretary at the local cotton gin, again bringing in some extra money for expenses, doing the bookkeeping as she had done for years in her husband’s grain elevator, now working with cotton receipts instead of wheat settlement sheets.

When my mother was sixty years old, she had a big birthday party, most everybody giving her gifts that had sixty items, one of which was a framed poster that listed “Sixty Things I Like About Dotmama,” bringing a big smile to her face as she read over the sixty statements, each one just a small part of the many likeable things about her.

When my mother was sixty-five years old, she had more grandchildren than she ever imagined, totaling 38 when the last was born four years later, everybody coming home for Christmas, filling up her little house on Christmas Eve, no breathing room, not a spare inch, bodies squeezed together, but smiles everywhere, laughter everywhere, the biggest smile and the biggest laughter coming from Dotmama because everybody had come home.

When my mother was sixty-nine years old, the great-grandchildren began, each year more added to the total, each name always remembered by her, each one bouncing into the house on their little feet to give Dotmama a big hug and a big smile, wanting her undivided attention as they told her a story of some adventure from their day, her eyes never leaving their face, her ears listening to their every word, a candy dish always on her table, full of treats for them.

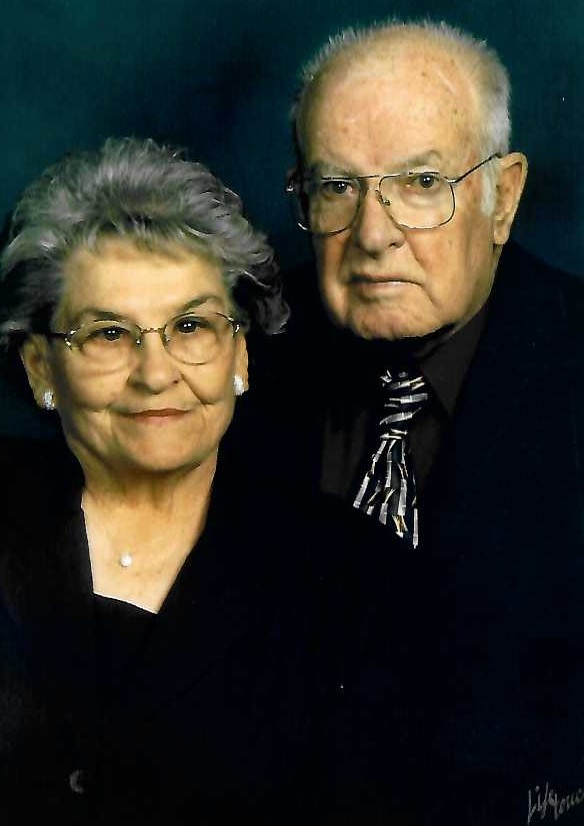

When my mother was seventy years old, she celebrated with her husband fifty years of marriage, the years going by so quickly, not the young people they once were, but still not feeling old either, happy for the joys that the years had brought them, accepting the sorrows that had occurred along the way, trustful that the God who had brought them this far would bring them further down the road of life.

When my mother was seventy-eight years old, she had to say goodbye to her husband, his final days difficult, incapacitated by a series of strokes, still she cared for him, helped by her children and grandchildren, until the day he drew his last breath, his weakened body on a bed surrounded by her and their children, tears flowing down many cheeks, but she remaining strong because she had to for her children, now that it was just her.

When my mother was eighty years old, she broke her hip, never regaining full mobility again, her birthday celebrated on the hospital grounds as she mended, but now requiring a walker, her spirit strong even if her body was weak, accepting of her limitations, never complaining, always cheerful.

When my mother was eighty-two years old, she broke the other hip, requiring a second surgery, telling us she was ready to go, but we would have to be ready to let her go. She survived the surgery, her mobility further limited, but she did what she could, saying her prayers every day as she had done all her life, visiting with family and friends who knocked on her door, even going to her grandchildren’s and great-grandchildren’s basketball games when she could, sitting on the sidelines in her wheelchair, watching them with all the joy imaginable, even if her back and body ached.

When my mother was eighty-five years old, her breathing made more difficult with each passing year, her heart becoming weaker with each passing day, she woke up one January morning with a fever, dying four hours later as she was rushed her to a hospital, breathing her last breath with thirty miles still to go, conscious to the end, her last moment a simple nod of her head, as if she had dozed off, and she was gone, leaving us with broken hearts, trying to figure out how to live in a world without our mama.

Today is Mother’s Day, the day we thank God for our mothers, something we should do every day, and so I thank God for the mother he gave me, and, although she may have been ready at the end to go, the truth is we weren’t ready to let her go, and the greater truth is we never would have been ready.

Happy Mother’s Day, Mama! I love you!

–Jeremy Myers