“The gatekeeper opens it for him, and the sheep hear his voice, as the shepherd calls his own sheep by name and leads them out.” (John 10.3)

Some years before she died, the American writer and civil rights activist Maya Angelou was a guest professor at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where she lived. She spent the entire first class having the students introduce themselves, while also spelling their names. When the class met for the second and third time, Ms. Angelou went around the room again to review the students’ names.

After the third instance of reviewing everyone’s names, Ms. Angelou asked the class, “Why did I just spend nearly twenty percent of our very valuable class time together making sure you knew each other’s names?” There was silence, so she answered the question herself. She said, “Because your name is a sign of your dignity. And when you recognize someone’s name, you recognize them, not just as human, but as a person.” She continued, “One of the greatest ways you bestow human dignity on someone is to call them by name.”

With that simple exercise, Ms. Angelou taught an even more important lesson than the one on the curriculum, reminding her students that having a name is a key to our humanity, and calling someone by name is a sign of respect for that person. Doubtlessly, she understood in a personal way that reality, her slave ancestors too often called by the racist epithet “boy,” rather than by their name, even though they were grown men.

Sadly, that denigration and humiliation of persons by taking away their name did not stop with slavery, but continued with the Nazi practice of tatooing numbers on each prisoner in their concentration camps, one more dehumanization act on a heap of atrocious acts. Even today, our penal systems utilize the same practice, having prisoners identified by number, not by name, proving again Ms. Angelou’s point that we give human dignity to one another when we call each other by name. We deny others their personhood when we deny them their name.

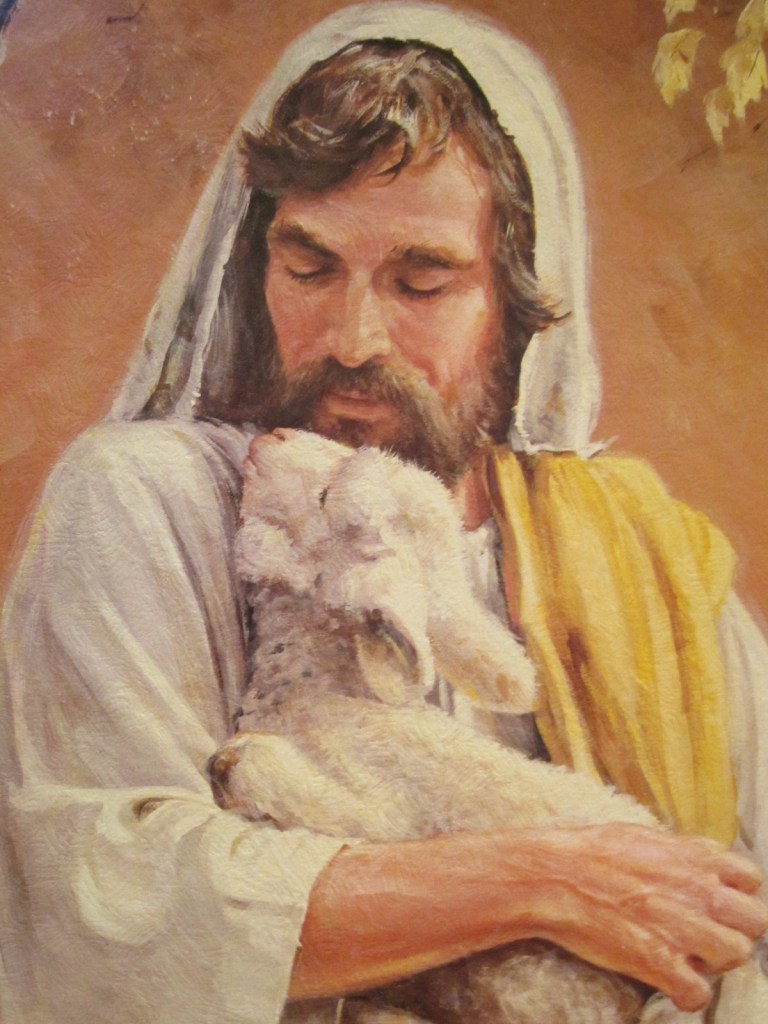

For that same reason, it is interesting that the Galilean Teacher, Jesus the son of Joseph, tells his followers that he, like a shepherd, calls his own sheep by name, his point being that there is a personal relationship between shepherd and sheep, close enough that the shepherd knows the name of each sheep.

As we listen to the Rabbi speak of his closeness to his followers in that way, we hear an echo of the words that Isaiah, that ancient prophet of Israel, spoke on behalf of the Lord God to his flock, his chosen people, when he reminded them of that same intimate bond when he said, “I have called you by name and you are mine.”

With those words, the prophet expresses beautifully the same closeness between the Great One and the little ones that the Galilean Teacher now says exists between him and his followers. He is so close to us that he knows our name. He respects each of us enough that he can call us by our individual name. He loves us so much that he never forgets our name.

We can find great comfort in that knowledge, knowing that we are important enough to the Lord God that our name stays on his lips, never forgotten, always whispered to us in the storm of day as we find our way and in the quiet of the night as we sleep away. As he speaks our name, he makes our name holy, even as his name is holy.

There was once a man, he’s gone now, his name was John, who made it his practice to always stop and talk to the street people he saw on the sidewalk, engaging with them in a conversation before he offered them some money for food or clothes. The first thing he did, he said, was ask the person what his or her name was.

In having them tell him their name, he wanted them to know that they weren’t some anonymous soul on the sidewalk, a dollar tossed their direction without looking their way. Each one was a person and, in having them tell him their name, he gave them, not only a dollar for a sandwich, but a chance to regain some part of their human dignity, some sliver of personhood, in a world that turned a blind eye to them.

If we are to imitate the way of the Galilean Teacher, then we come to understand the same thing, that it is not enough that he knows our name, but we also must know each other’s name, showing in that way mutual recognition, mutual respect, mutual love. To follow the Teacher carries a responsibility to call one another by name, just as the Galilean Teacher does, because it is as the Most High God does.

That gifted writer and preacher Fred Craddock, in one of his many stories, writes about how he and his brothers used to mow the cemetery lots at Rose Hill Cemetery in Humboldt, Tennessee, a summer job they took to help support the family. He says that when they took the job, they saw a strong, high fence across the way. Behind the fence were something like sixty or seventy graves.

Seeing those graves, they asked the man in charge if he wanted them to go over the fence and mow the grass there also. The man answered, “Nah. That’s Potter’s Field. Those gravestones don’t even have names.” Craddock says he asked the man, “Well, who were those people?” The man said to him, “Who cares? They died in jail, died paupers, died without family. Don’t mow there, just let the weeds grow.”

Craddock instinctively knew there was something not right in the whole situation, not right that the gravestones had no names, not right that they were supposed to let the weeds grow over the graves, not right that the man in charge said, “Who cares?” Craddock, even at that age, just knew you didn’t treat people that way, even if they are dead.

Today, the Galilean Rabbi offers us assurance that he will never treat us that way–even if we are behind bars, poor as dirt, and with no kin who will claim us, but will always call us by name, as a shepherd does his sheep, because we are special to him, important to him, someone he never forgets.

And as he remembers us, he also asks us who follow his way to do the same–to call each other by name. It is the first step in forming a Christian community, the first move we must take before we sit down together at the table to break bread.

–Jeremy Myers