“About three in the afternoon, Jesus cried out in a loud voice, ‘Eli, Eli, lemi sabachthani,’ which means, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’” (Mt 27.46)

Some say God stores the tears of the righteous in a flask. He safekeeps them because these prayers offered to him in wet drops are more precious to him than dry words, much the same as a mother collects the tears of her small child in her open hand. Perhaps it is true that the tears of the just ones move God’s heart in a special way, if for no other reason than their hearts are most alike to his own heart.

On that dark day that we call Good Friday, although the only semblance of good to be seen was nailed to a cross, there were enough tears from his beloved son to fill flask after flask, filled to the brim and overflowing, liquid fire from the deepest part of a shattered spirit. Heaven’s storeroom had stacks of flasks after that horrendous day.

His beloved son left behind him a trail of tears. Days before, as he had approached Jerusalem, looking at it from a distance, a heavy dew in the air, he wept over it, saying “If this day you only knew what makes for peace, but now it is hidden from your eyes” (Lk 19.41). Once in the city, he shared the passover meal with his closest friends, knowing in his heart that one of them was a traitor, his eyes moistened with tears as he said, “One of you will betray me” (Mt 26.21).

Afterwards, late in the night, he went into the Garden to pray, telling his three closest comrades, “My soul is sorrowful even to death” (Mt 26.38). Another said that “he was in such agony and he prayed so fervently that his sweat became like drops of blood falling on the ground” (Lk 22.44), tears doubtless mixing with the sweat as they poured down his cheeks onto the grass.

Once the evil men had put ropes on him and hauled him to the court of Caiaphas, they stripped him bare, beat him raw, spat spit wads at his face, the spit from their mouths joining with the tears from his eyes, as his body shook with pain and as his heart broke from the hurt. When morning came, they placed a beam of wood onto his back, forcing him to carry it to a hill outside the city walls, where they would nail him to the cross, spectators on the streets cheering and hooting.

As he stumbled with the heavy beam on his back, falling several times onto the ground, he wept from the agony and from the abuse, his tears only bringing more slashes of the whip onto his back and more laughter from his persecutors’ mouths. Some women along the way wept as well, and with a shallow voice, breaking as he spoke, tears filling his eyes, he uttered, “Daughters of Jerusalem, weep not for me, weep for yourselves and for your children.”

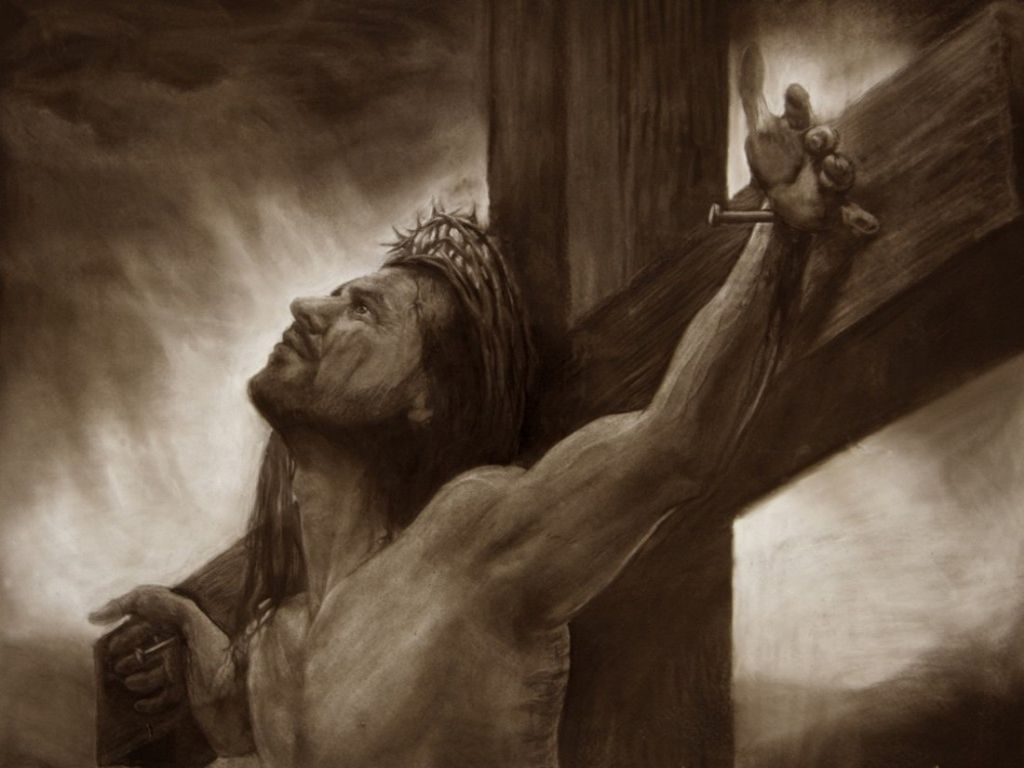

Only more torment awaited him, more torture, more tears as one of the soldiers grabbed a hammer and began to pound nails into the tender underside of his hands, binding him to the wood, then moving to his feet, and doing the same with spikes, so that he was nailed to the cross, as a beatiful butterfly is pinned onto a display board. As the nails entered his flesh, he cried out, the pain immense and unbearable. More tears flooded his face, spasms of pain and agony shaking his broken and bruised body.

There he roasted in the sun, a human sacrifice on a spittle of wood, hanging between heaven and earth, insults added to the injury as onlookers and busybodies mocked and flocked around, not a shred of sympathy for his suffering, not a pittance of pity as he cried on his cross.

After several hours, unending minute after minute of torment, his body collapses on the wooden beam and his lungs collapses from the pressure put upon them, and he cries out one last time, words from the old Hebrew texts that he had learned as a child, now uttered from parched lips and a dry tongue, “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” (Mt 27.46). Then he gave up his spirit, no more left to give, no fight left in his heart, no tears left in his eyes. He was empty. It was finished. Finally.

Archbishop Romero, the saint of San Salvador, spoke these words in a sermon before his own execution as he stood before an altar of sacrifice, “This,” he said, “is the great disease of our world today: not knowing how to love. Everything is selfishness. Everything is exploitation of human beings. Everything is cruelty and torture. Everything is violence and repression.” He was probably right. Most everything brings tears because, in the end, we simply do not know how to love. Worse still, we do not want to know how to love.

The sacred texts say darkness covered Jerusalem as the beloved son took his last gasp of air. Some say it rained on crucifixion day. Maybe. Or maybe God took the many flasks of tears that he had stored from his only Son’s stay upon the earth, a place where we still do not know how to love, as we ought, and, tilting over each flask , he flooded the earth with teardrops, his own commingling with those of his son, washing clean the sins of the world, giving us still another chance to show we’re better than we look on paper, his mercy upon the world measured in tears.

There is a very old story told by the storyteller Megan McKenna that tells a similar story of God’s mercy on us. Many years ago there was a Rabbi who led a small congregation in a poor village in Eastern Europe. On the night of Yom Kippur, the day of atonement, as the group gathered to ask God’s forgiveness for their failings, the Rabbi begged for some sign from the Holy One that their prayer was heard and that his mercy would be given to them.

The Great and Holy One heard the Rabbi’s plea and he answered it in this way. “Have Tam offer your prayers to me and I will accept all of you back into my heart, forgiving all your failings, and showering my mercy upon you.” Shaken by the answer from the Most High God, confused by his directive, the Rabbi shook to his shoe soles, for he barely knew the man called Tam, because he hardly ever attended service in the synagogue.

Yet, when the Rabbi looked over his congregation, there, on that night sat Tam, a poor, uneducated man, who worked late each night, making it impossible for him to attend synagogue except on rare occasions. Those who knew something of him said he was good-hearted, although seldom seen.

The terrified man was brought to the front of the synagogue after the Rabbi had called out his name. The Rabbi spoke to Tam, “I prayed for mercy and forgiveness for all of us on this night, and the Most High God, blessed be his name, told me that we would be forgiven and we would be taken back into his heart only if you pray for us, if you offer a prayer to God on our behalf.”

Tam was speechless as he stood shaking before the assembly. Illiterate, he could not read the customary sacred prayers in the book, so he did not know what to do. Still, the Rabbi was insistent that God would only take back the community into his heart and grant them another year of blessing, grace, and mercy if Tam prayed for them.

Finally, Tam agreed, but he said to the Rabbi, “First, I have to go get my prayers.” The Rabbi nodded his head and so Tam ran from the synagogue to his little house, returning some while later, standing again in front of the people, now holding in his hands a large earthen flask.

Tam lifted the flask high above his head and he prayed out loud: “O Holy One, you know I am not good at praying, but I bring you all I have. This flask holds my tears. Late at night, even when I am tired, I sit and try to pray to you. And I think of my poor wife and children and how they have no clean clothes to wear to service and are ashamed to come to the synagogue, and I cry.”

“And then I think of all the hungry ones, the beggars on the steps of the synagogue and in the streets, in the cold and the rain, miserable and all alone, and I cry some more. And then, God, I think of what we do to each other. I think of all the gossip and hate, all the quarrels and wars, and I think of you crying, God, of you looking down on us, hurting one another so much, and I know that you weep for us always.”

Tam continued, “God, I cry for you and how we must break your heart and sadden you so much. Please, take my tears, accept my prayers, and take all of us back into your heart once again. Give us your blessing and forgive us in your great mercy.” As he spoke his last words, Tam took the flask and poured his tears onto the stone floor of the synagogue.

There was a long silence, until finally the Rabbi spoke in a halting voice, “God has heard the prayer of Tam, and we are forgiven. We are once again the people of God. Let us live this year with grateful hearts.” The people sang a song and then left the synagogue quietly. But they never forgot Tam’s prayer or his flask of tears.

And so, they made sure there would be less to cry over in the year to come. They looked at Tam and his family more kindly. Some even reconciled with their enemies. And always they thought of the tears of God. So goes the story of Tam, who presented his tears to God as a prayer for mercy upon the people for their sins.

So goes a still more ancient story, this one of a beloved son, who offers his tears for the sins of the world, a world lost and without love. And as that man wept, tears dropping from his eyes, he offered this last prayer from his heart, “Father, forgive them, they know not what they do,” as he hung upon a cross at a place called the Skull, where people, without a drop of love in their veins, had crucified him and the criminals there, one on his right, the other on his left.

Today, we can only hope the tears of that beloved son were received by the Most High God, placed into the flask he keeps at his side for tears from the just upon the earth, and that those same tears are now weighed out in the mercy God rains upon a world that still does not know how to love.

–Jeremy Myers