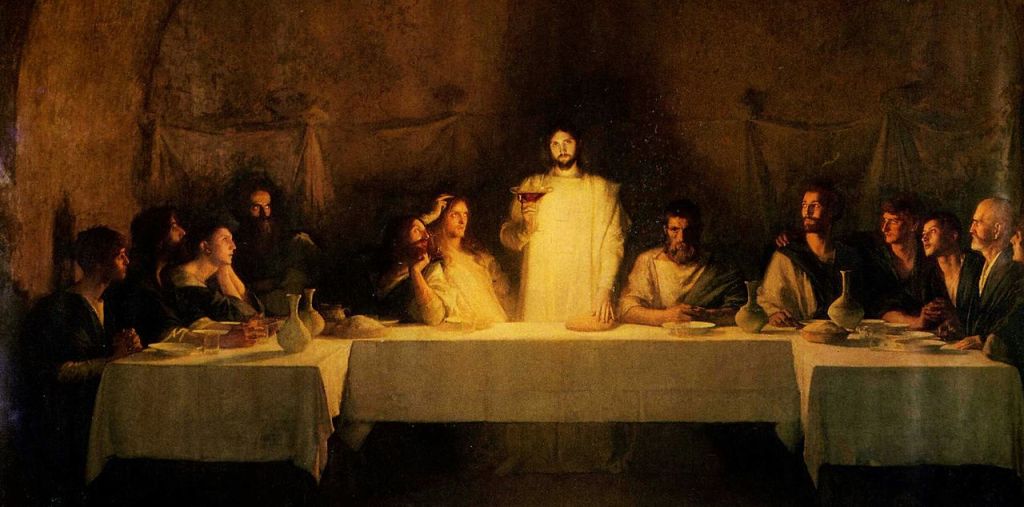

“When it was evening, he reclined at table with the Twelve.” (Mt 26.20)

When the day came when it was time for the older couple to downsize, give away, or throw away the things they had accumulated over their long life together, their new place too small for the accumulations of a lifetime, the hardest decision was what to do with the beautiful old mahogany table that had been the place of all their family meals over the years.

They finally decided to sell it, the husband finding a young mom who was moving into her first home, eager to have a table of her own. His wife didn’t like the idea of her table going to someone who wouldn’t appreciate it. “She probably doesn’t know the difference between real wood and plywood,” the wife said. When the young woman arrived to pick up the table, she was kind, thoughtful, and helpful.

The older woman, still not sold on her, made a point of telling the younger woman how fortunate she was to get the table. The younger woman listened respectfully, at the end telling the older woman how long she had been saving for a dining room table, not just any table, but something beautiful that could be a place for her family to make happy memories, a table that, when her time came, she would pass on to her daughter, so that she also could have a table like this one.

The older woman’s attitude softened as she heard the words, watching as the younger woman’s husband and brother-in-law gently and carefully placed the table in the back of their truck, stepping back into her now empty dining room, remembering with a slight smile how the table that once was there had made them a family. Now it was time for the table to do the same for a younger couple. A table, it seems, when we get right down to it, is never just a table.

The Christian religion, like any family, began at a table. For that reason alone, a table may be the more correct symbol for Christianity, even though the cross usurped primacy of place in the later decades of the first century after the Lord. It is important for us to remember the centrality of a table, not only at the end of Jesus’ days, when he reclined at table with the Twelve, but during the preceding years, when his sitting at a table with others was front and center.

Even a hurried perusal of the sacred texts demonstrates that the Galilean Teacher frequently sat at table with others, using a meal as a means to feed people’s souls as well as their bodies, inviting them to break down barriers as they broke bread together. Many of his most important teachings came as he sat with and spoke to those who joined him in a meal. His earthly mission, expressing divine love to a world at odds with God, was enacted and symbolized by his sharing a meal with anyone and everyone, especially the least, the last, and the lost of the world.

After inviting Levi, the tax collector for Rome to follow him, an unthinkable act in Palestine during Roman occupation, Levi holds “a great banquet for Jesus at his house,” the guests including “a large crowd of tax collectors and others [who] were eating with them” (Lk 5.29). That association with such a high profile persona non grata results in harsh condemnation of Jesus by the religious leaders, who “complained to his disciples, ‘Why do you eat and drink with tax collectors and sinners?’”

Jesus’ response is as simple as it is instructive, answering their judgmental criticism with the statement, “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance.” With those few words, Jesus expresses the very nature of divine love, a love so inclusive, so demonstrative, so expansive that no one in God’s creation is excluded from it.

Not only did Jesus personally express a love that welcomed the prostitutes and sinners, he also argued that God had an intensive love for these lost souls, people who had lost their way in the world, who had lost all hope of God’s love. Jesus flipped inside out and upside down the assumed criteria for divine love, telling the religious leaders that law-abiding, hand-washing, holier-than-thous would find themselves bringing up the rear in the parade to heaven, with prostitutes and sinners entering the kingdom of God before they did.

He offers the same important teaching when another tax-collector, the short-statured man named Zacchaeus, catches Jesus’ eye, dangling from a tree branch on the side of the road, Jesus smiling up at him and saying, “Zacchaeus, come down immediately. I must stay at your house today” (Lk 19.5).

As before, the implication is that Jesus sits down at a table with Zacchaeus, invoking–as before–the wrath of the religious leaders who grumble, “He has gone to stay at the house of a sinner.” Jesus rebuts the criticism, instead saying, “Today salvation has come to this house because this man too is a descendant of Abraham. For the Son of Man has come to seek and to save what was lost” (Luke 9-10).

Another example is found on the occasion of a Pharisee “inviting Jesus to dine with him, and he entered the Pharisee’s house and reclined at table” (Lk 7.36). Because the host in this instance is a Pharisee, again Jesus meets criticism, this time for allowing a woman with a bad reputation to wash his feet with her tears, after she learns “he was at table in the house of the Pharisee” (Lk 7.37).

The Pharisee is apoplectic, melodramatic, and emphatic with his disapproval, whispering to the other stiff shirt on his right, “If this man were a prophet, he would know who and what sort of woman this is who is touching him, that she is a sinner” (Lk 7.40). Jesus overhears the snarky aside, putting the Pharisee in his place with these words, “When I entered your house, you did not give me water for my feet, but she has bathed them with her tears and wiped them with her hair.”

Jesus brings more criticism down upon his head when he says, “Her many sins are forgiven because she has loved much” (7.47), wherepon “the others at table said to themselves, ‘Who is this who even forgives sins?’” (Lk 7.49). As before, Jesus, choosing to sit at the table with prostitutes and sinners, a wholly unholy thing to do, will find himself caught in the crosshairs of the Pharisees, who cannot stomach someone who fills his stomach at the same table as sinners. Still, despite the criticism, Jesus would say, “When you give a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind” (Lk 14.13), in other words, not the prim, not the proper, not the prosperous,

Knowing the risks he was taking in breaking social norms, Jesus understood that his table fellowship was not making him friends with people in high places, saying as much when he blasted his critics for their hypocrisy with the observation, “John came neither eating nor drinking and you said, ‘He is possessed by a demon.’ I came eating and drinking and you said, ‘Look, he is a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners’” (Mt 11.19).

It makes perfect sense, then, that the man of Nazareth should end his days with a meal, sitting at a table with his hodgepodge of sidekicks, all of them low class, most lowbrow, some low life. It was, as he liked to say on more than one occasion, a rather good example of the heavenly banquet table, where the first will be last, the last will be first, and where the wedding guests are street people, while the snobs, the snooty, and the sanctimonious are locked out.

As Jesus sat at table with them, his last night alive, he ate bread and drank wine as he made a simple request of them, “Do this in memory of me,” by which he meant they should continue to gather around a table, the lost souls with soiled reputations and few social graces, remembering that once upon a time a man walked among them, who made them feel so incredibly loved by God, showing them by his words and by his deeds a love so full of forgiveness, so full of acceptance, so full of understanding, that it had to be otherworldly because, for sure, it wasn’t anything like the measured, the miserly, the miniscule love they had experienced on earth.

“Tables are never just about food.” When the American liturgical expert, Nathan Mitchell, wrote those words in his book about the Eucharist, he had, without a doubt, the sacred texts on his side, because Jesus’ sitting at a table with others was never just about food. It was about unity, about community, about solidarity, all God’s children, every last one of them, seated around the same table, marinating in the juices of God’s love. The table was the place where love was passed around as much as the mashed potatoes.

In one of her books about small-town life in Alaska, Heather Lende shares a story about an old native who made the family dinner table just such a place. His grandson, like everybody else in the family, sat down every night with his grandfather at that family table. “Every dinner was a kind of Thanksgiving,” he said. “For an hour or more, it was always the same stories: who we were and where we came from.”

On this day, as we reenact the evening when the Lord Jesus sat down at the table for a last meal with that ragtag, riffraff band of brothers and sisters, it also is a kind of Thanksgiving, or Eucharist as the word is in Greek, a time when we tell the same stories, remembering him who asked us to remember him, particularly when we are at the table, remembering in this way who we were, remembering where we came from. A table, as all followers of Jesus learn, is never just a table.

–Jeremy Myers