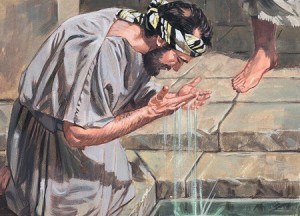

“They said to him, ‘How were your eyes opened?’ He replied, ‘The man called Jesus made clay and anointed my eyes and told me, “Go to Siloam and wash.” So I went there and washed and was able to see.’” (John 9.10-11)

Some years ago, a team of neuroscientists conducted an experiment, wanting to understand better the functioning of the brain. This experiment, perhaps ghoulish to most of us, required them to sew shut the left eye of a newborn kitten with small stitches. After three weeks, they removed the stitches to test the kitten’s vision.

Shockingly, the kitten could not see out of its left eye. It had no vision. The scientists concluded that the brain of the baby kitten had assumed that the left eye was not needed, since it was not being used, and so shut down the flow of necessary neurons that would have allowed eyesight to function. They also learned that once the brain had made that determination, it could not be restarted. The kitten remained blind.

That experiment offers us important information, not only about how the brain works, but also about how our capacity to see works. It is another example of the “If you don’t use it, you lose it” school of thought. If we do not use our eyes, then we may lose them, like mules that worked in black-as-night ore mines often did.

For that matter, the principle applies in more than just the physical sense, working as well in the spiritual sense. If we want to see as God sees, then we must train ourselves to open our eyes in a whole different way. Here again, we must use our spiritual eyesight or we will lose it.

That may be the most important message of the story of the blind man whose vision is restored, a story we find in the gospel of John that is read to us on the Fourth Sunday of Lent. The man’s sight is returned to him through the healing works of Yeshua bar Yossef, also known as the Galilean Teacher, and, as we learn from the story, his spiritual insight also is revived through his encounter with this worker of wonders.

As is always the case with this evangelist and his telling of the signs and wonders of the Galilean, there are layers to this story, requiring a careful reading of each layer. On the surface, the story presents the events whereby an unnamed man who is blind is healed by the hands of the Galilean preacher who creates a salve of his saliva mixed with sand and who then smears some of the salve onto the eyes of the blind man, instructing him to wash it off in the Pool of Siloam, after which the man is able to see again.

Thereupon multiple exchanges occur between the healed man and others, including his neighbors and the religious leaders, all of whom ask the same question of him, “How were your eyes opened?” When the man answers that it was “the man called Jesus” who healed him, a debate escalates, with the Pharisees insisting that “a sinful man cannot do such signs”, while the healed man insists, “One thing I do know is that I was blind and now I see.”

As the tensions increase, with the religious leaders unable to believe that the Galilean restored the man’s sight, and the healed man ably holding to his belief that his sight came through this worker of signs, it becomes clear on another level that the Pharisees are the ones who are spiritually blind to the identity of the Galilean because of their refusal to believe, while the once-blind man is the only one who truly sees him as a worker of wonders because he believes in him. The difference is clear as the healed man challenges the Pharisees, “I told you already and you did not listen. Why do you want to hear it again?”

This story of the healing of the blind man forces us to put ourselves in one or the other camp–with those who think they can see but are blind, or with those who once were blind but now can see. Yes, the evangelist purposely plays with irony here, wanting us to understand that the people who claim to see may not see at all, while those who were considered blind are the only ones who really see the truth. Like Tiresias in Greek mythology, the blind prophet in Thebes who was famous for his clairvoyance, again it is the blind who leads and guides those who are able to see.

As the story continues, the evangelist presents the disciple–or believer–as the one who moves from blindness to sight, the one who sees what others refuse to see. The disciple is the person who finally can say, along with the blind man, “Now I can see.” The unbeliever, on the other hand, is like the Pharisees, who are self-assured of their ability to see, even when they cannot. “Surely we are not also blind, are we?” they derisively ask the Galilean. We know the answer, even if they do not.

That is the same question that the evangelist wants us to ask ourselves as we ponder this story. “Surely we are not blind, are we?” The answer is found in how we see others. Do we see the other in front of us with a critical eye, harshly judging and labeling him or her, rather than seeing a person little different from ourselves? Do we jump to conclusions about others based on skin color, or the clothes on their back, or the language they speak, or do we see beneath the surface details a beautiful person made in the image of their Creator? Do we walk past the man on the street, never turning an eye to this person in need, or do we take the time to see a human being in need, who reaches out to a fellow human for help?

Determining how we respond to each of these situations, it should be easy enough then to answer the question. “Surely we are not blind, are we?” Again, it is based on how we see others. Do we see them as God sees them, or do we see them as the world around us sees them? Cleverly, the evangelist shows that the neighbors are blind because they only see the man as a beggar, just as the Pharisees are blind because they see the Galilean Teacher only as a sinful man. In their quick judgement of others, both groups failed to see the person who really stood before them.

The problem for us, as with the kitten who could not see because its brain was rewired not to see, is that we often enough have trained ourselves not to see others as alike to us, but as different from us. Products of our culture, playthings of our environment, participants in our privileged mindset, we have turned off our capacity to see others as the same as us, blind to the reality that we are fundamentally brothers and sisters, each one of us created by the same God who is the source of love, called by him to love one another with the same ferocity of love as he has for all of us.

The news media carried a story some years ago about a 45-year-old man who was born blind and who recalled the taunts he endured as a boy as classmates stood in front of him, laughing in his face and saying to him, “How many fingers am I holding up?” Then they would say, “Ha ha ha, you can’t see!” As the man said, “I felt humiliated every day.”

Now, these years later, a successful man with a career, he was asked by a friend to reach out to ten-year-old triplets who also were blind and who were being bullied. “I felt compelled to help,” he said. “I could totally relate, because their story was mine as a kid.” Each weekend, the man meets with the boys, teaching them practicalities like shopping and doing laundry and using their canes. He also introduced them to restaurants, boxing, and ice-skating. The triplets call the man their dad and say, “We didn’t have a role model before him.”

Helen Keller, another person who was born blind, but who also had more insight than most everybody else, once wrote, “As selfishness and complaint pervert the world, so love with its joy clears and sharpens the vision.” Those few words are proof enough that she was able to see more clearly than those with good eyesight, a blind woman understanding the essential truth that love clears our vision about our shared humanity, while selfishness clouds our ability to see those around us as one with us.

It is the same message that the evangelist offers those of us who would follow in the footsteps of the Galilean Teacher, would-be disciples, urging us to train ourselves over time in the ways of love, each decision to love others flooding the world with a little more light, rather than training ourselves in the ways of hatred, each decision to hate casting the world into further darkness.

The ancient rabbis understood well this same message. They tell the story of a teacher who taught his students what it means to see rightly. One day the teacher asked them a simple question, “When can you tell when day is breaking?” One student, quick to answer, said that it is when you look down the road and you see an animal and there is enough light to tell whether it is a fox or a dog.

“No,” said the rabbi, “that is not the right answer.” So a second answered the question. “It is when you look at an orchard and you can tell the difference between an apple and a pear tree.” Again the rabbi shook his head. The students, now frustrated, begged the rabbi for the right answer. “Tell us,” they said, “when can you tell when the day has dawned?”

The rabbi looked at them in the eye and said, “Day breaks when you look at a man or a woman and know that he or she is your brother or your sister. Until you can do that, no matter what time of day it is, it is always night.”

“Night is coming,” the Galilean Teacher forewarned his followers in this story of the blind man. During these tumultuous times in which we live today, we must decide again if it will continue to be night for the world, or if we will allow the dawn to break over the horizon, shooting beams of brilliant light into this world, casting out the darkness with the rays of love from eyes that now see.

–Jeremy Myers