“And he was transfigured before them . . . Then from the cloud came a voice that said, ‘This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased.’” (Matthew 17.2,5)

Sometimes the smallest stories have the biggest truths, as we see again in this story. One day two caterpillars were crawling across the grass when they saw a butterfly fluttering on its wings above them. They looked up at the strange sight, one of them saying after a while to the other caterpillar, “You couldn’t get me up in one of those things for a million dollars.” Little did either one of them know, at that moment, that they were meant to be a butterfly, flying high in the air, when they grew up.

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” Unfair as it is, we adults often press children with this weighty question of life, when they still are incapable of coming up with a decent answer. Maybe we grown-ups, on some unconscious level, want children to get a head start in searching for an answer to the big question of life, knowing it takes a lifetime to get to the answer.

Then again, maybe the better question to ask children is “Who do you want to become?” That question, at the very least, accepts the premise that who we want to be can’t be fully answered yet, the answer unsure and unfinished until we draw our last breath. Until then, the best we can say is that we are still becoming specifically someone. And becoming that someone is always a life-long task, built on a mountain of decisions, a challenging climb to the top, far from our base camp at the bottom.

The 20th century British writer Evelyn Waugh once answered the question in this way, “My vocation is to become Saint Evelyn Waugh.” Simplistic at first glance, profound at second glance, the answer hides a great truth, which is this–so long as we live and breathe, we are meant to become that person God imagined us to be when he molded us in his mind’s eye.

That person who achieves the fullness of who he or she was meant to be is called a saint by Waugh, by which he probably meant someone who makes more visible the image of God on their person than most of us manage to do. Yet, another way of saying much the same thing would be to speak of such a person as a “beloved son of God.” Or, just as rightly, a “beloved daughter of God.”

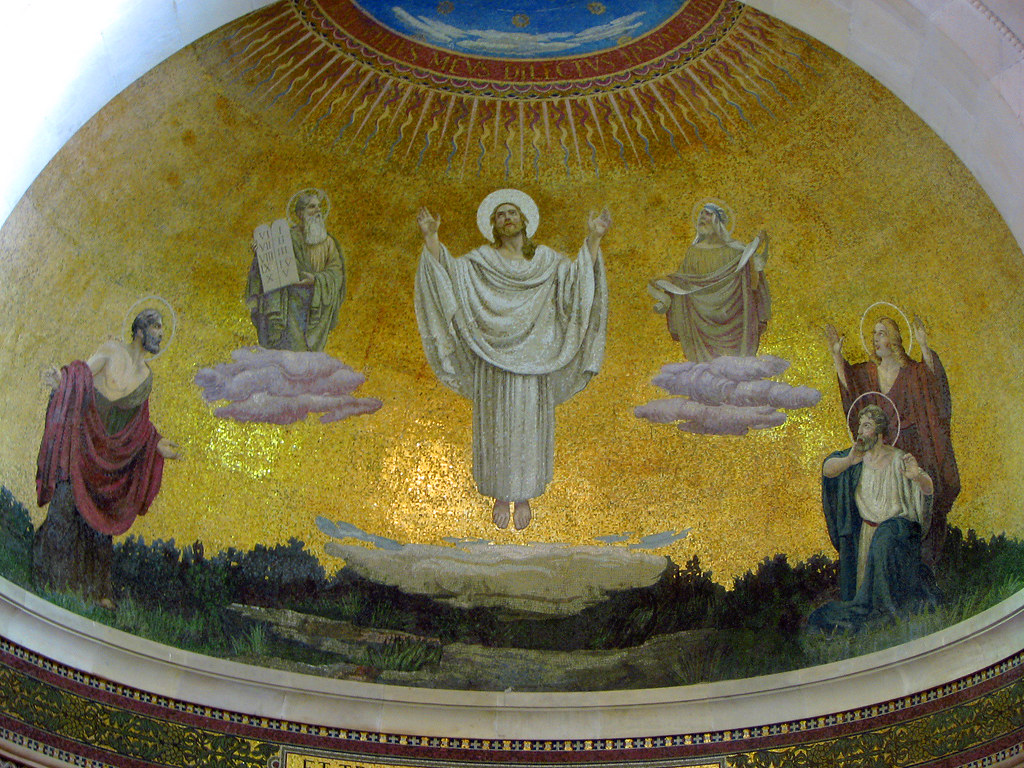

We find the same phrase in the Sacred text selected for this Second Sunday of Lent, a text that tells us of the transfiguration of the belittled son of the carpenter into the beloved son of God, the scene taking place atop a mountain, where the true person of the preacher from Galilee suddenly radiates outwardly, rays of light shining all around him, so brightly that three of his most trusted disciples covered their eyes, blinded by the presence of total goodness, and fell to the ground, humbled by the sight of absolute saintliness.

“This is my beloved son, with whom I am well pleased.” The disciples swore they heard the words spoken from a cloud that hovered over the mountaintop, the divine presence clothed in the foggy mist, a decisive declaration of divine distinction now given to this Galilean preacher, because he has become fully the person that God had asked him to become.

That glimpse into the soul of the Teacher, a spirit aligned perfectly with the spirit of God, so much so that they are one, allows the disciples to see the man from Nazareth at his core, while, at the same time, allowing them to see who they also were created to become, that is, a beloved child of God.

That transfiguration of Rabbi Jesus, the summation of his inner self shown in a split second, revealed the possibility of our also being called beloved sons and daughters of God, so long as we keep unsullied that same seal of divine love that was put upon our skin on the first day, shaped as we were by Love to become stewards of love.

That moment of revelation on the mountaintop is retold to us during this season of Lent with just cause, this season being a time of return, a time of rebirth, a time of reversals, as we confess with contrite hearts that we are not yet who we are supposed to be, stifled by a sinful inclination that has made its home in our hearts, stunted in our spiritual growth by a series of wrong turns on the road of life.

The ashes sprinkled on our foreheads at the start of the season, an ancient symbol of repentance, serve as a sober reminder that we are not yet the persons we were created to become, persons originally graced with goodness, beauty breathed into our bones by the source of all that is beautiful, now marred and scarred by our trysts with all that is ugly in this world.

This time of renewal would ask us to answer honestly these questions: Are we yet where we want to be? Are we now who we want to be? Are we content with what we have become? If our answer is yes, then Lent provides no purpose for us. If we answer no, then Lent holds a host of challenges for us, as we face the truth that we still have not released fully the love that was poured into our hearts by the God who is love.

Here, we can be aided by an adage among neuroscientists, a sentence something like this, “What goes into the brain is what the brain becomes.” The simple statement seeks to explain how our brains become programmed to do what they do, whether it is speaking a new language, or mastering eye-hand coordination, or working complex math equations. We train our brains to become what they are by the activities we select to put into them. Our brains become what we want them to be.

Just as easily applicable to other key areas of life, we can see the same principle at work with our spiritual development, that inner drive towards goodness, our desire to live up to our Father’s expectations that we become his beloved sons and daughters. If we are to meet those expectations, then we have to ensure that we put the right stuff into our souls, stuff like kindness and generosity and selflessness, gradually shaping our spirits over time to reflect the same light and life and love of God that beat deep within our hearts, until the day when our hearts finally become like his heart.

While the transfiguration of Yeshua bar Yossef occurred in a matter of minutes on that mountaintop, our own transformation into pure light and love will take a lifetime, if for no other reason than our heart is not as unspoiled, as undivided, as uncompromised as was the heart of the Galilean Teacher, his heart beating in total unity with the heart of God. The repair of our own heart will take more time and much work.

However, with persistence in doing good, and with resistance to doing evil, and with assistance coming from God, we eventually can traverse the distance between who we are and who we are to become, step by step, mile after mile. This becomes our walk in life, our climb to the top of the mountain, where we also await the beatific vision of our own full transformation into that beloved son, that beloved daughter of God, when our love is as immeasurable as the fountain of divine love from which we draw.

The songwriter and singer, Joni Mitchell, gave voice to this same sentiment in her song, “Woodstock,” written during a time of war, of soul-weariness, of too much wrongdoing, when she sang these words, “I came upon a child of God/ He was walking along the road/ And I asked him, where are you going/ And this he told me,/ I’m going on down to Yasgur’s farm/ I’m going to join in a rock ‘n’ roll band/ I’m going to camp out on the land/ I’m going to try and get my soul free/ We are stardust/ We are golden/ And we’ve got to get ourselves/ Back to the garden.”

“Then can I walk beside you/ I have come here to lose the smog/ And I feel to be a cog in something turning/ Well maybe it is just the time of year/ Or maybe it’s the time of man/ I don’t know who I am/ But you know life is for learning/ We are stardust/ We are golden/ And we’ve got to get ourselves/ Back to the garden.”

“By the time we got to Woodstock/ We were half a million strong/ And everywhere there was song and celebration/ And I dreamed I saw the bombers/ Riding shotgun in the sky/ And they were turning into butterflies/ Above our nation/ We are stardust/ Billion year old carbon/ We are golden/ Caught in the devil’s bargain/ And we’ve got to get ourselves/ Back to the garden.”

–Jeremy Myers