We should put the blame where it belongs. The three kings are the ones to blame for the commercialization of Christmas. While their intentions may have been good, the results are less than stellar, no pun intended. As the annual holiday approaches each year, sales starting earlier and earlier, with stores putting snowmen and stockings and sweaters on shelves in October, you will find people bemoaning how the reason for the season has been lost, with everyone’s attention on shopping, with no one glancing at the crib, not until they walk into church on Christmas morning.

Maybe these so-called wise men weren’t so wise. There is documentary proof, starting with their directional deficiency, getting lost on their way to Bethlehem, finally asking directions from the last person in the world they should have asked, wicked Herod in his palace in Jerusalem, the man out for the young baby’s blood. When their GPS starts to work again, connecting with a star in the night sky, they ride atop their camels into the little town of Bethlehem, finding themselves in front of a stable, wondering if the star in the sky went haywire again. Surely this wasn’t the right place.

Entering the dilapidated barn, their sniffers smelling fresh animal dung, lifting their royal robes up to their knees so they didn’t step in any of it, they walked towards the back, where a small light shone, giving a glow to the small quarters, squinting their eyes to see a small baby in a crib, with his mom and dad sleeping on the hay to each side. So, was this supposed to be the new king of Israel, a child wrapped in clean rags cut into strips, sleeping in a manger, about as far from a palace as a person can get?

As the child’s parents stirred and stared at these unexpected visitors, wondering who and what these visitors were, dressed to the gills in royal finery, clearly out of place like a polar bear on the Pacific coast, the baby awoke, sensing strange movement, opening his eyes to see three tall men with fancy headgear offering him gifts. His mother took the gifts from them, knowing better than they that a baby doesn’t play with gold, frankincense, or myrhh. A toy or two, maybe a teddy bear, would have been fine.

Good intentions aside, the gifts seemed as wacky as one of those ugly Christmas sweaters, but the gracious parents smiled, offering thanks to the visitors, inviting them to spend the night in the shelter of the stable. Stealing a glance around the small enclosure, the royals declined, saying they needed to be on their way, insisting they had a long trip ahead of them, wanting to try a different route home.

In that moment, as gifts were unwrapped in the lean-to, Christmas became commercialized. Or, better said, the seeds were planted, connecting forever after Christmas with gift-giving, a practice that grew over the centuries into the extravaganza it is now, where mountains of gifts are stacked beneath the Christmas tree, looking like a hastily built high-rise, a tremor or two enough to topple the whole structure.

Of course, it is not the same everywhere, especially where people have less money to spend, fewer stores to rush into on Black Friday, where smaller gifts, if any, are more the norm. But even in such circumstances, people are bombarded with Christmas advertisements and cultural pressure to buy, buy, buy, forcing shoppers to put gifts on layaway, often borrowing money to cover Christmas expenses.

Truthfully, the Magi cannot carry the full burden of blame for our excesses, only for the idea of giving gifts during the season. We did the rest, moving further away from the modest crib in Bethlehem, advancing steadily towards the check-out counter at Target, our baskets loaded down, our credit cards maxed out.

Each year, as Christmas draws near, I remember my grandmother’s stories about her Christmases as a young child growing up on the Great Plains of Nebraska, a place where pioneers hoped to eke out a living, a place that saw more struggle than success, where survival was not assumed. As I sat on her lap, listening to her stories, she would tell me that her Christmas gift most years was an orange. Yes, one orange.

Since I lived where oranges were considered ordinary, seen in every grocery store, packed in every school lunch, it confused me that she only got an orange for Christmas. Yet, as she told the story, it was clear, even those years later, that she was happy to have received that orange on Christmas morning. Some Christmases, she said, she would get a few mixed nuts, three or four to shell before eating, savoring each one of them, these nuts another rare thing in her childhood.

Without a doubt, those few walnuts and pecans made an impression on her, as most things do on a child, because every year that I knew her she bought a bag of mixed nuts as they became available on the store shelves a few weeks before Christmas. She allowed herself only one bag. When it was empty, she bought no more. The stores still stock them at Christmas time. I think of her every time I see a bag of them. I don’t need to buy one, enough sweet memories returning with just the sight of them on the shelf.

For years, I would watch her bring the old nut cracker from somewhere in her closet, placing it on the kitchen table, starting to crack nuts on this circular contrivance seemingly made from a tree, the varnished bark still on the outside, with the inside hollowed out so the shells could fall, as she used a small mallet to crack them in the center of the bowl.

Truly I believe each time she tasted one of those nuts she remembered those Christmases decades before, huddled in the small sod house on the plains, probably a winter blizzard making it unbearably cold, or surely a cold wind from the North causing her and her siblings to huddle together near the open fireplace. She always carried a smile on her face as she ate one of those mixed nuts, the smile itself exuding gratitude.

As she raised her children years later, now living in a two-story farmhouse, my grandmother carried the simplicity of her childhood Christmases with her into her home, although she lived in Texas, a changed place in a changed time. But she had not changed. For her children, she bought oranges and a small bag of mixed nuts. My mom, when telling stories of her own childhood Christmases, said that this was her gift each Christmas, except for the one Christmas she received a Shirley Temple doll.

My mom was proud of that doll, but Grandma, practical to her core, put the doll up on a shelf, occasionally allowing my mom to play with it, mostly fearing that she would damage it. Doubtless, my grandmother considered the doll an extravagant gift, something requiring special care, a gift better suited for visual enjoyment, less so for actual play.

My mom remembered it as the only Christmas she received something other than an orange and a bag of mixed nuts. Yet, she never spoke disparagingly of the simpler gifts on the other years. She was happy with the piece of fruit and a few walnuts. She was grateful for the smallest of gifts. Everything, we would have to say, was simpler back then.

After she had married and had begun her family, my mom broke tradition, with the times changing, now an orange and a small bag of nuts no longer thought of as something special. Still, she was careful in providing for our Christmas gifts, since money was not as plentiful as the children in our house. Yet, she was able to give gifts that I remember decades later, knowing each of her children so well as to give us something that we would consider special, even if not high-dollar.

The most memorable for me was a very small desk and chair that I received when I was in the second grade. I assume my mother understood that I was more the student than the sportsman, so the BB gun went to my older brother, while the desk went to me. I spent hours sitting at that desk, making use of it as the years passed, with my legs eventually growing too long for the space beneath it, even then a prescient sign that I would spend much of my life behind a desk.

With little effort, I can recall other Christmas gifts I received from my mom and dad through the years, each one special enough to be remembered. In the early years, apparently I went through a period of personalized items, probably a popular phase for the times, one year receiving a signet ring with my initial, another year a leather belt with my name engraved on it–my two older brothers receiving similar belts that year–and a later Christmas a personalized bracelet. I still have two of the three gifts, although I don’t wear them anymore. None would fit.

Another of my most treasured Christmas gifts, made more valuable to me with each passing year, is a book of Christmas stories that I received in the fifth grade. I wrote inside it in my eleven-year-old handwriting, “This book was given to me on December 24, as a Christmas Gift. 1967″ Once again, my mother intuited that a book would mean something special to me. With decades behind me now, I have shelves of books, too many to count, but that book is worth more to me than any other book I have.

While still in the elementary grades, I received a watch one year, a bicycle (refurbished at a cost of $10, but still new to me), another year two Dickey turtlenecks that I requested, one black, the other white, apparel that was popular in those days, though impractical–I would learn–because they were so itchy. I spent most of the time scratching.

In high school, there was the year I received a winter coat. Another year, a bean bag chair, emblematic of the 70’s, when non-conformity and out-of-the-box thinking resulted in just such a thing that could still be called a chair, one thing from that crazy decade that has stayed, unlike bell bottoms or bushy sideburns.

My bean bag chair, a clover green color, served me well, even into college years, although I had to refill it once with Styrofoam pellets, a messy effort, not recommended unless the bean bag has been squashed so flat from use that you’re on the floor with nothing but a crumpled layer of plastic separating you from the linoleum.

Today, I am sure these gifts may seem to others as simple as the orange that my grandmother received at Christmas once seemed to me, but–like her–I remember each of them with fondness, each a marker of my growing up years, an annual calendar not on paper, but imprinted on my mind as the Christmas that I received this or that gift. Even now, I can flip through this calendar of memories, remembering my boyhood, reflecting on those long ago Christmases, rejuvenating gratitude for the things given to me.

We live in a time now, it would seem, when many of us have less gratitude, although we receive more things, whereas my grandmother’s generation was more grateful, although they received fewer things. A strange inversion has occurred with the passing years–the more we have, the less gratitude we have; the less we have, the more gratitude we have. Somewhere, somehow, I fear ingratitude has become ingrained in our culture today.

By no means do I intend to engrave this personal observation onto stone tablets for the ages, but there is enough experiential evidence to make a case for it. An 89-year-old woman recently said, with sincere sadness in her voice, that the only time she sees her great-grandchildren is when it’s time for them to receive their Christmas cards from her, into which she has tucked a check. She added that she never receives a thank you note from them afterwards.

Of course, even back in the days of my childhood, there were the signs of creeping commercialization into Christmas, although I did not see as much of it then as I do now. The ominous signs–more gifts being better than fewer gifts, bigger gifts being better than smaller gifts, more expensive gifts being better than less expensive gifts–already were slipping through the doorway of Christmas, like the stray cat that sneaks through the kitchen door when we’re not looking. These signs were more subtle, but still strong.

Thinking back, I remember my fourth grade teacher–a seasoned educator and a good teacher overall–seemed unaware of how uncomfortable some of her students became when, upon our return from Christmas break, she would ask each student to stand in front of the classroom, telling their classmates the gifts they had received for Christmas.

It is not difficult to understand how this exercise could become excruciating for some students, dividing the class into have’s and have not’s, allowing the advantaged to showcase their gifts, causing the disadvantaged students to lower their heads and their voices, quietly telling the class the gift or two they had received, hurriedly returning to their seats. To this day, I cannot understand how she overlooked the obvious discomfort and disparity. It was a display that served no good purpose.

One particular year, after the class day was over that had included this broadcasting of gifts that had been received, I learned from a classmate that he had not received any of the gifts he said he had. He told me he made up his list so that he wouldn’t be embarrassed in front of the class. He found that lying about his Christmas was easier than telling the truth, diminishing the shame that this spectacle brought to him, no one the wiser except for me, whom he considered a confidant.

The irony, one that would take years for me to realize, was that this same teacher read to us O Henry’s short story, “The Gift of the Magi,” before Christmas break, as opposite a message from her post-Christmas message as a summer breeze is different from a winter blizzard. In that early 20th century story, O Henry tells of a husband and a wife who have no money, but who want to give each other a gift at Christmas. It is Christmas Eve, so there is little time remaining to find a gift for each other.

The husband decides to sell his pocket watch to get the money necessary to buy his wife hair combs to go into her long and beautiful locks that he loved so much. She, on the other hand, went to her hairdresser to have her long locks cut and sold, receiving twenty dollars. She finds a watch chain for her husband that cost $21.

Later that evening, the wife–Della–gives her husband–Jim–the chain for his pocket watch, admitting to him that she had sold her hair to buy the gift. Jim, surprised and moved by his wife’s love, tells her that he had sold his watch to get the money to buy her ornamental combs for her hair. While neither Jim nor Della now can use the gift the other has given to them, still they realize the great love they have for one another, a love that is priceless.

As I see it, that story much better captures the beauty of Christmas than a classroom recitation of our Christmas bounty, O Henry teaching us that the value of a gift is not determined by the dollars spent, but decided by the love given, offering us a lesson on selfless giving instead of selfish getting. It is a story, I believe, that deserves a place in every home as children wait to unwrap their Christmas gifts.

Some time ago, Lynn Johnston, the creator of the comic strip, “For Better or For Worse,” had a comic that showed seven-year-old Lizzie cracking open her piggy bank. She says, “Look! I got nine dollars an’ eleven cents to spend on Christmas!” Her twelve-year-old brother, Michael, is not impressed. He says to her, “You can’t buy something for everyone with nine dollars an’ eleven cents, Lizzie!” She answers, “I’m gonna try!” Michael responds, “Well, they’re sure gonna be cheap presents.” Lizzie, unperturbed, answers assuredly, “Nothing is cheap, Michael, if it costs all the money you have.”

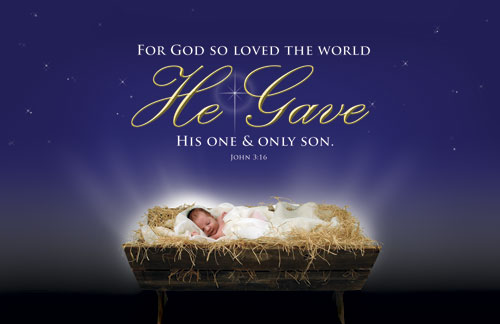

There, in the few words of a seven-year-old girl, we find the essence of Christmas. So, maybe we might want to shift our attention from the gifts that the Magi brought to the child in the crib, gifts that may have cost these kings very little personally, and look instead at the giver of another gift that first Christmas. That gift is best described to us by the writer John, who in his gospel, wrote these beautiful words, “For God so loved the world that he gave us his one and only son.”

–Jeremy Myers