My mom was a winter person. I am not. Whereas she looked upon winter as the time of year when everything good happens—such as snowmen, Christmas carols, and arctic temperatures—I still look upon winter much the same as a smart bear would. When the weatherman forecasts the first warning of frost, I eat a big meal, go into my cave, and sleep until the smells of spring wake me up. I think it is a perfectly good way to pass the winter months, in the oblivion of hibernation.

Not my mom. She saw the seasonal swing from fall to winter much the same as a child who waits for Christmas, except this was a Christmas that lasted for several months, not just for a single day. With each sign that winter had set in, she became more excited. I never heard her complain about winter, even in her old age when her bones picked up on the weather forecast long before the weatherman on TV, and when the meat on her bones had become sparse as a lean cuisine TV dinner, providing her little, if any, protection against the cold.

Searching for some sensible explanation for her winter season bias, I only can surmise it is rooted in her childhood when summer days spelled long workdays in the sun, while winter summoned up more pleasant memories. Not that she and her siblings went scot-free during winter months—they did not—but the work hours were shorter, because the days were shorter, and the work was less intensive, at least for her. Also, with the annual Fall picking of cotton now completed, winter with its less strenuous demands must have felt like freedom does to a jailbird.

She often shared with us stories of her winters as a child on the farm. She told us that her first chore as a little girl of no more than five years of age was to go outside to the woodpile and to bring an armful of wood back into the house, wood that often had a layer of ice on top and had absorbed the cold so that the logs felt like over-sized icicles. Not to mention the spiders that found the underside of the cord wood a great place to spend the night.

She admitted it was cold work, but also understood it was her responsibility to keep the wood-bin in the house filled. Her brothers had the more difficult job of facing the winter winds and ice-covered ground to find their way to the barn, where the hungry livestock waited for food and where the cow or two begged to be milked. So the few steps to the woodpile paled in comparison.

That wood, of course, was needed for the wood stove in the dining room that was meant to keep the farmhouse somewhat warm—at least the bottom floor—and for the wood cook stove in the kitchen that cooked the meals. There was a second chimney in the parlor, but it was never used. She didn’t know why. Knowing my grandmother, I think she saw the second chimney as an extravagance.

In preparation for the cold weather, my grandpa would have to make several runs through the pasture to the north of the house towards the river bottoms before winter hit, hacking limbs from dead mesquite trees and chopping bigger branches into smaller ones, so that the woodpile would be stocked and stacked before the first blast of frigid winds. There were times, of course, when he had to hitch the horse and pull the wagon through the pasture on a cold winter day because the woodpile was getting low. Now, we just go to the thermostat and push a button to get more heat.

For these and other reasons, my mom had reasons to dislike winter, but she didn’t. She talked how cold it would get on winter nights in the room upstairs where she slept. Her dad, she said, didn’t allow the fireplace downstairs to burn during the night hours because of a fear of a fire, which meant the house—upstairs and downstairs—was without any heat every winter night, regardless of the low temperatures.

My grandmother made hand-stitched quilts and feather-filled ticks for her children so that they could stay reasonably warm during the nights. It was not until my mom went to school that she learned some children’s moms sent a heated brick, covered and carried in a pillow case, with them to their beds so that their feet would stay warm. She found something funny in the fact that her mom never heated a brick for them to take upstairs.

Looking back, I figure my grandmother, who had grown up on the prairies of Nebraska, and who knew firsthand what a real winter blizzard felt like, didn’t believe anything in Texas could approach one of those, and so didn’t feel any need to coddle her children with a warm brick, proof again that winter for an Eskimo does not mean the same thing as winter to an Floridian.

It was very cold, my mom liked to say, when she stepped out of bed in the morning as a child in that two-story farmhouse, and raced down the steps to get near the wood stoves, where her dad had started the wood fires needed to warm the house and to cook breakfast. Fortunately, her mother drove her to school, not because of the cold, but because her mom went to church in the mornings.

Later, when she became a mother herself, she didn’t expect the same toughness from us. I’m glad she didn’t. As we know, the toughness factor decreases with each generation. She kept our house warm and she turned on the flames on her gas cook stove at night so that the heat from it would move from the kitchen, up the stairs, to the loft where we slept. I don’t remember ever being cold at night and we didn’t have to carry heated bricks upstairs to stay warm.

Often, my mom talked about one of her favorite winter activities on the farm, when she and her two older brothers would grab a pair of skates and run to their nearby pond, which they called a tank, so that they could skate. She, being the lightest in weight, was told to test the surface of the ice. If it showed any cracks from her light weight, it wasn’t ready for the bigger boys. Her face took on the joy and the fun of her younger self when she talked about the many hours of those winter days that they skated on the pond to the west of their farmhouse.

The cold months of winter brought more than just ice-skating. There was hunting for deer and rabbits and other wildlife. Her brothers did the hunting for the bigger game, but she enjoyed going with them at nights when they hunted birds that sat on the ice-covered limbs of the mesquite trees or slept beneath the eaves of the big barn, standing a short distance away from the farmhouse, the moon sending muted beams through the thick clouds beneath it, turning the barn into a dark shadow, with the farm horses and the milk cows huddled inside straw-covered floors to escape the cold that seeped through cracks in the wood slats of the barn door.

She never forgot those winter nights of hunting birds with her brothers. Years later, she enjoyed taking her young boys, armed with their BB guns, out into the winter night, where we would walk in the still winter air, searching with a flashlight for a sparrow or two, hunched atop a nearby boxcar or hanging onto a high line for dear life. I did not often make this foray into the winter night because I was hibernating like the smart bear that I was.

One thing that I did stick my head out of hibernation for was the making of snow ice-cream, another of my mom’s favorite wintertime things to do, but which could only be done if there was snow and if it was the right kind of snow. Whereas the Eskimos have fifty different words for snow, we had only two—dry and wet. Dry snow was good for making snow ice-cream. Mama would go outside with us and we would scoop up with our hands huge clumps of snow that we put into a mixing bowl. Rushing inside, we would watch as Mama magically turned snow into ice-cream.

Snow ice-cream was something early pioneers also made, a procedure that made sense because it was the only ice cream available to them, depending on nature’s freezer rather than a Whirlpool freezer. Maybe Mama learned it from her mom who must have eaten it when she was a child in Nebraska where the snow piled up to the top of their sod house. This winter treat was passed down the generations, without any loss to its appeal or our appetite for it.

The recipe, as far as I know, is unchanged from those times. Add some milk, sugar, and vanilla to the snow and mix together. If you’re going to try it sometime, do not overdo the milk since the snow melts quickly when liquid is poured onto it. There are no measurements. Go with taste and texture. We’d eat bowl after bowl of snow ice-cream until we had a full stomach and a brain freeze.

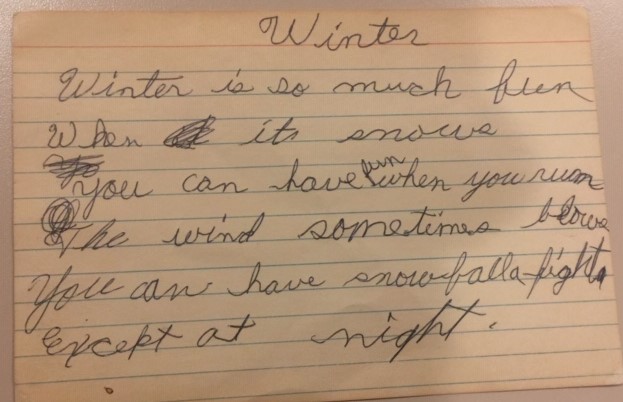

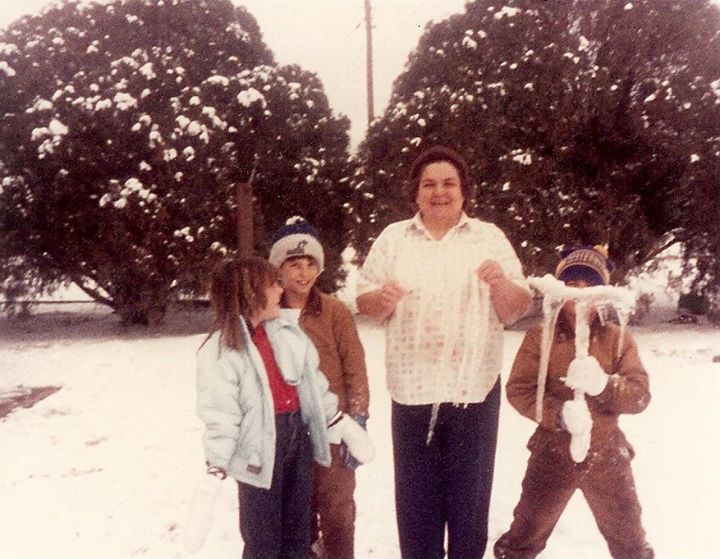

The wet snow, on the other hand, provided its own fun also. My mom enjoyed snowball fights, which required wet snow in order to form big round snowballs that would mold nicely into hand-formed cannon balls to toss at one another. Tactical training was not necessary. Simply grab a clump of snow in one palm, use the other palm to shape the ball, and throw as many and as fast as you could. This was such fun for my mom that she didn’t stop when we were grown, but moved onto the grandchildren, teaching them the fun of snowball fights. Like us, they took to it—with one or two exceptions—without looking back.

Something to be pointed out, an oddity really, was that my mama didn’t wear a winter coat in most of these outdoor activity. If it was extremely cold, she might wear a light jacket, but more typically she went into the winter weather in short sleeves. Her body somehow was habituated to the cold weather, probably from those winter nights in the old farmhouse where she fell asleep with the North wind shaking the windows and snow drifting underneath the windowsill. So, she never found the cold temperatures intolerable or uncomfortable, as we would have without a coat to shield us.

Once, my dad had the grand idea to get our mom a coat for Christmas. Wanting to buy her a new dress coat to replace the old one that was a hand-me-down from our grandmother, he asked us children to assist him in getting the coat for her. He gave us the money and the older ones, myself included, went into a department store in Abilene where we figured we could find a coat for Mama. We were kids on a mission and we were determined to succeed.

There was one problem. We didn’t know her size. But, excited as we were to know our mom was getting a new coat, we didn’t let that lack of information erase our enthusiasm. We parlayed and improvised. Seeing a woman in the aisle and thinking she looked close in size to Mama, we asked her if she would try on the coat so we could see if it fit.

With a good dose of Christmas spirit and a big smile on her face, she agreed to try it on for us. As she stood there before us, making a turn or two on her feet, we huddled together like a quarterback with his lineman, whispering our call and hoping it would be a scoring throw. We thanked the kind lady in the aisle for her help and we bought the coat.

When Christmas came and Mama tried on the coat, it was tight, but she acted like it was a perfect fit. Our eye for size was not as good as we had hoped and the woman in the store was not as close a twin as we thought she would be. When we explained how we had come to the decision, Mama thanked us and told us we had done a good job. The coat stayed in the closet most of the time, but that may have had nothing to do with the fit, and more to do with the fact that Mama just didn’t wear coats.

Oddly, my favorite picture of my mom has her in a coat. It was in her later years and she had gone on a winter drive with some of my sisters, now grown and home for the holidays. I suspect she put on the coat more for their comfort than for her own. It is not a heavy coat that she wears, but there is no sign that she is uncomfortable, although she stands on snow-covered ground and icicles hang from trees. They are at the old farm, where so many good memories were made.

Behind Mama is the old barn. It is missing some boards, but still sturdy. I keep the picture on my bookcase so that I am sure to see it often, a reminder of my mom, but also because I know on that day she was right where she wanted to be, standing in the snow, remembering all those good times on the farm, and looking at her daughters in the distance, and thinking how good God was to her.

Years later, when we buried her, it was a winter day in late January. As a special gift to her–I am sure–God made certain it was a cold crisp morning, with the wind blowing freely from the North, and winter reigning in all its glory. You know, Mama always loved winter. It was a good ending to her story.

—Jeremy Myers