Everybody knows there are two kinds of people in the world. Those who do and those who don’t. Those who can and those who can’t. Those who ask and those who don’t ask. Out of a need to render a complex world more understandable, it seems we like to compress our knowledge into binaries: a dog person or a cat person; a PC user or a Macintosh; a leftie or a rightie. Our brains, much like a page of programming, prefers to sort everything into 0’s and 1’s.

Included in those 0’s and 1’s we also can add a hugger or a non-hugger. Here, I am talking about a people hugger, not a tree hugger, although the binary works with the latter just as well as it does with the former. (People either hug trees or they don’t.) As we know from experience, when we make a new acquaintance–not a tree, in this instance–the either a hugger or not-a-hugger binary is one of the first interpersonal matters that we have to navigate. Can you see the Mona Lisa giving hugs? I don’t think so. Once that dilemma is determined to mutual satisfaction in the current situation, we can move onto other important binaries, such as coffee or tea, Coke or Pepsi, queso or hot sauce.

I pondered this question of “to hug or not to hug” again when I watched a little boy hugging his mom. It did not seem to be a question for him. He was a hugger. That was clear in how tight he wrapped his small body around his mom’s upper torso. On the top, his arms encircled her neck, while on the bottom his tiny legs circled behind her back–not a full circle, because his legs were little legs, not big legs. His head fit beneath her chin, much like a ball and socket joint. And, as far as I could tell—from my line of sight—he was wound so tightly around her that he made it look as if her body had grown him on the outside and not on the inside, as I’m sure she did back when.

Soon, within moments of his climbing to that perch on his mother, as a cat might do on a windowsill warmed by the sun, the boy fell asleep. And it seemed to be the restful sleep granted only to young children and to old dogs. The boy, with his mother’s arms supporting him, rested peacefully there, safe from the monsters and the monstrous tasks that trailed him in the world of grown-up people. To have awakened him or to have pried him away were equal parts unthinkable and unpardonable.

And, as happens in those rare moments of clarity in life, all the false binaries fell away and I saw how we were meant to be when our world was more perfect and more amenable than it is now, before we decided we were better apart than together. That child reminded me that we were made to hug and to be hugged. It is not something we were supposed to choose. It was chosen for us by evolutionary forces or by divine forces, and the move away from it has to be seen as a deviation from the design. You could not look at that child as he hugged his mother, and as she held him in her arms, and conclude otherwise.

I think mothers already know this to be true, since they are the ones who have seen firsthand that a hug is pre-programmed into their child and they have learned the many languages that a hug speaks for their child before words can do the talking. A child hugs her when he is happy and he hugs her when he is sad. He hugs her when he is afraid and when he doesn’t want to be away from her. He hugs her when he is tired and when he is hurt. Moms know that a hug is the medicine chest that fixes most of the scratches and bruises in a little boy’s life. And in a little girl’s life also—we must include the binary here.

My mom was a second-half-of-life hugger, at least in my recollections. Not that she didn’t hug us when we were hurt or crying or sick. Of course she did. We knew she loved us, but hugs were not her first language of love. But when her grandchildren came along, she didn’t need a reason to hug them. She spontaneously wrapped her arms around them if they were having good days just as easily as she did on their bad days. Her arms always were open.

I heard her explain once that it was a decision she made later in life, expanding beyond her own childhood experience with a Germanic mom who tended to associate tenderness with going soft on a child, although–in fairness–I feel my grandmother went soft in her old age also, since as a small boy I crawled into her lap on many occasions.

Still, the explanation rings true. One of my favorite movies has to be Neil Simon’s “Lost in Yonkers.” Watch Irene Worth play Grandma in that movie and we see Germanic reservation in spades —surely exaggerated for effect, but still true for the most part, I suspect. Bella says of her mom in the movie that she never allowed her children to cry. And–if my memories serve me well–I don’t think she ever hugs anybody either. Had she done so, I think it would be remembered because it would have been so out of character for her.

My mom chose to be a different kind of Grandma. And as a result, her grandchildren loved her and did not fear her, like Jay and Arty did their grandmother in the movie. My mom lavished hugs on her grandchildren in the same quantity as the candy dish on her kitchen table, which was always full. She went the full Monty with hugs, so to speak.

As a student of psychology many years ago, I learned that babies that were not held and hugged showed symptoms of physical illness and even suffered death because of being deprived of human touch. Most of us have read of the study of the war-time orphanage where young babies were dying in their cribs in high numbers, and it was not until women were brought in to hold them that their symptoms reversed and their health improved.

However, it was only lately that I learned another thing that psychology has unearthed. Psychologists, like pirates, are always finding buried treasure in the terrain of human traits. Now, they have discovered that not only do children thrive with hugs, but grown-ups also do better when they are hugged. Not just better—they live longer. Everybody—adults and children alike—have better health if they are hugged. In fact, one psychologist suggests that the daily recommended dosage of hugs should be eight per day, if we want a longer and a happier life.

Or, as one well-known writer, whom we could call a hug specialist, although I think he usually goes by the name “Dr. Love,” suggests, “We need four hugs a day for survival. We need eight hugs a day for maintenance. We need twelve hugs a day for growth.” If we take seriously his health advice about hugs, he says we can expect our immune system to improve, our heart rate to improve, our blood pressure to go down. Those are some of the bigger payoffs. There are more, such as improved sleep, fewer symptoms of depression, and rejuvenation of the mind. Who wouldn’t want those things? And to think they’re just a hug or two or eight away.

It really gets interesting because it seems a hug from a pet works to our benefit as well. We already knew this truth on some unconscious level because pet owners—good ones, not bad ones—love to give and to get hugs from their furry friends. Our life expectancy increases if we have a pet with which we can connect. By the way, it has been shown that dog owners receive more health benefits than cat owners do. ( I know, another of those binaries.)

We also should state the obvious to avoid any confusion. The closer we are emotionally to the person to whom we give or from whom we receive hugs increases the health benefits. The opposite is just as obvious. Hugs that are considered invasive or unwelcome decrease the benefits and increase the harmful effects. But everybody should know that—but as the rule of binaries suggests and as experience proves—there are people in this world who just don’t know that simple fact.

Believe it or not, there is a hugger in the Bible. One I know of, but probably more if I knew the Bible better. His name was John and because he liked hugs he became known as John the Beloved. We find him in one of the gospels where we see a great example of his generosity in giving hugs. This particular instance happened after he saw Jesus was deeply troubled because one of his followers was about to betray him. Who of us wouldn’t need a hug in those circumstances?

So, seeing Jesus so distressed, “one of his disciples, the one whom Jesus loved, was reclining at Jesus’ side . . . And he leaned back against Jesus’ chest and said to him, ‘Master, who is it?’” History has held onto that hug by showcasing it in paintings and on tapestries and in stained-glass windows. It is probably the most famous hug in history. Or, maybe the second, after the famous photo of the V-J Day hug a US Navy sailor gave a stranger in Times Square, although that one includes more than a hug, and so should be disqualified.

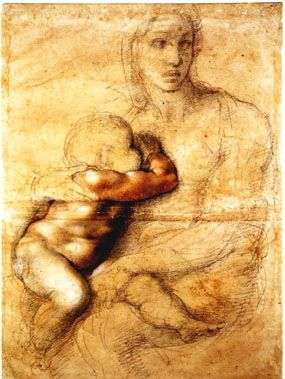

When my mind wanders, as it did when I saw that little boy hugging his mom, I let it go, like a grasshopper jumping from green plant to green plant. Sometimes you just want to see the path it will take. And as I contemplated that child in his mother’s arms, I thought of the many paintings of the child Jesus in his mother’s arms—it seems every Renaissance painter earned his chops doing one—the Madonna and child showing us that hugs are as holy as they are healthy. I specifically thought of Michelangelo’s pencil drawing in which Mary, with the child at her bosom, looks into the distance, as if she can see the cross already, and foreseeing how she will hug the body of her dead son to her bosom for the last time.

I considered, then, that the eternal rest that we have tried to describe in every possible way from clear golden streets to chanting glorious choirs to celestial golf courses might be expressed just as well by the image of an everlasting hug. Yes, heaven can be seen as being held in the arms of the One who made us, and who loved us from the first moment, and who hugged us as she sent us into this wide world, hoping we would find similar holy arms to hold us here.

It is not a leap, as I see it, that our dying should be a return to those same arms that held us before we came here, arms that were the first to hug us, and of which we always carried a faint memory, those maternal arms of God-our-Mother to which we have compared and contrasted every set of human arms that ever held us in a hug.

Were our end to be such that we would find ourselves in those arms again as that small boy was in the arms of his mother, the two of us so close that the beats of our hearts are one, the sense of peace so complete that nothing could take it away from us, then that end, I say, would be blessed indeed. And we could but hope that it would be eternal as well.

—Jeremy Myers