We never had a “Cheers” bar–the TV place “where everybody knows your name and they’re always glad you came”–but we had Mick’s for almost thirty years, and it also was someplace where you could go and everybody would know your name. While our small community could never be confused with Boston, we still found as much to like about Mick’s as Sam and Norm and Frazier found likable about that Boston bar.

Mick’s was a filling station in the old-fashioned sense of the word. You pulled into one of his two fill-up lanes and Mick would come out of his garage to pump the gas for you. Rarely would you have to wait for another car and just as rarely would the two pumps be going at the same time. While the gas was being pumped into your car, Mick would wash the windshield and windows and he always would pull the hood to check your oil.

At the start, there was no such thing as a gas credit card–or I don’t remember there being one–so you handed Mick the cash and he made change. If memory serves me right, he might have kept a running tab on a piece of paper for certain customers. Later came the credit cards–until Mick thought those companies were getting too big a chunk of the change. He kept a sign close by that read–“Our credit manager is Helen Wait. So if you want credit, go to hell and wait.” He had another sign on the wall. It read, “Our cow died, so we don’t need your bull.” You could say Mick believed in straight talk.

If you needed an oil change or a tire changed, you could go around to the of south side of the garage and pull into the one well that Mick had to service vehicles. Mick never had to ask you your name. He knew it. And he knew the names of the other people in your family. And he knew the names of relatives you didn’t know you were related to. Mick knew everybody’s name.

Mick had served in the U.S. Army during World War II. He talked about the time he was stuck in a foxhole for two weeks. Somewhere along the way he picked up the habit of chomping on a cigar in Archie Bunker fashion. He didn’t come back home to Texas right after the war, but stayed in California, where he met his wife, Audrey, who was a transplant from Iowa during the war years. Mick and Audrey both worked in a manufacturing plant for a while. Later, Audrey worked in a beauty shop.

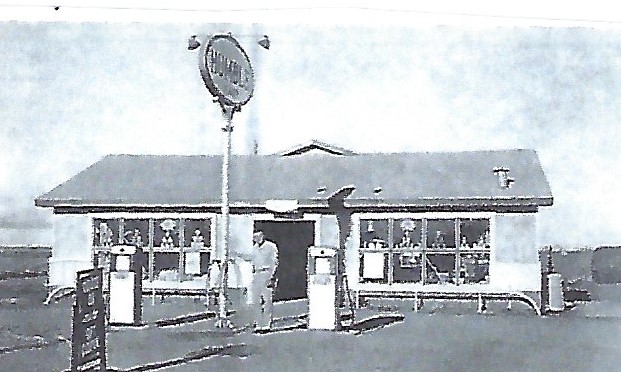

Mick came back home to Texas at the start of the 1960’s and brought Audrey with him. Maybe he decided California was becoming a crazy place in the 60’s. Audrey adapted well to the Lone Star State. Except she never called him Mick, as we did. He was always Mike to her. They moved in with his mom, who was getting up in years. Audrey didn’t do hair anymore–except her own–but she cared for Mick’s mom while Mick worked at his garage. Mick’s mom would live until she was 91 years old. For the first few years after he returned, he rented work space from a neighbor who had a Humble filling station in the front and a radiator shop in the back. Soon enough, they parted ways and Mick built his own station catacorner from the old garage he had rented.

Mick started out as a Humble station, then went to an Enco station, which became an Exxon station. I suppose the signs outside the station served as markers for the changes in the oil business. Somewhere there is an old picture that shows the Enco sign. My oldest brother says Mick built his station around 1965. I go with his recollection because he’s older than me and he has a better memory than I do. Also he went to Mick’s more than I did, although one of my younger brothers was there a lot more than both of us combined.

When the one and only grocery store closed in the community around 1968, Mick bought the old candy display case from the store and moved it to the front room of his garage so the kids would still have a place to buy candy. This was before 7-11 stores or Allsup’s offered gas and groceries under one roof, at least around these parts.

It was the same candy counter that my mom used to get candy from when she was a little girl. The grocer’s wife was partial to my mom and she would give her a piece of candy whenever my mom and her mom went to the grocery store. Less often when the grocer was there. So that candy counter had history. Generations of curious children had stared into its glass panels marveling at the many kinds of candies it contained.

After Mick had moved the old wooden counter into his own place, he stocked the usual candy bars and candies that kids loved and also had one of those old-fashioned coke machines that you opened the lid and pulled a drink out of the iced-down bottles, You probably won’t find one of those machines anywhere except in some yard cluttered with antique pieces from the sixties or even earlier.

Once Mick had the candy counter inside his garage, it became a place for the local children of the community and not just for the local grown-ups. While the adults went about the grown-up business of getting gas put into the car by Mick, the children darted into the garage and bought a candy bar from Audrey. If she wasn’t behind the counter, we waited until Mick finished with the gas fill-up.

It seems a bygone day that kids could get excited about a candy bar or a soda pop, as they were called back in the day. But we did. As children, we didn’t have much spending money. Allowances for kids were something we heard about from the kids in the neighboring town, but not something we knew anything about. There was a brief period when my mom would give us older kids a quarter at the end of the week and the younger kids got a dime.

If we managed to scrape together a few cents (to be taken literally), we usually made our way to Mick’s to buy something from his candy counter. A piece of bubble gum–as it was called back then–sold for one cent. He also offered refunds on pop bottles–a nickel for each bottle. So we searched the ditches for bottles that could be cashed in for candy. His garage was within walking distance and so we made our way (barefooted, as a rule) down the dirt road–about two blocks–and made a beeline for the candy display. Mick made a special point of opening his garage for a half-hour or so on Sunday mornings just so the kids could get a coke or candy bar.

We were happiest when the Tom’s truck had made its weekly run with a new supply of candy because then we had more choices. I almost always went with a Zero candy bar. To this day, I consider it a Zero bar a special treat. Unfortunately, they are not stocked as much as Snicker’s or Hershey bars or M & M’s–all good by all means, but a still a second to a Zero.

I remember Mick also carried Taffy. You don’t find it much anywhere anymore–to my knowledge–at least not the long narrow sheet with three-colors that you bit into and pulled with your teeth with the strength of dog biting onto a piece of a tree limb. In later years, Mick got one of those fancier coke machines, where you didn’t need ice water to keep the drinks cool. Sad to say, I don’t think drinks pulled out of those new machines tasted near as good as those ice-cold ones out of the old machines. Just my opinion.

Another thing Mick’s provided was a venue for the old guys who wanted a place to hang out and to catch up on the local events and to trade stories about the old days. Mick had a few old chairs to the left of the candy counter where these guys could sit and smoke and share their day. As I recall, it seems he had several old metal tractor seat welded onto some type of steel stand that served as chairs. The other seats were your standard issued metal chairs–no cushion, no comfort, no complaints.

When afternoon came and the sun was a scorcher, Mick and a few of the regulars liked to play “Shoot the Moon.” He had an old card table set up in the garage and the guys would grab a chair and play this domino game for hours. There was some money involved, the losers giving a quarter a game. I think that was the rule. I was just a kid, so I didn’t play dominoes. I would not have had the quarter anyway. You’d have to ask my younger brother who made Mick’s his home away from home. That’s where he learned to play dominoes, learned to change a tire, and learned to cuss.

So, whenever you walked into Mick’s, especially on a hot afternoon, you’d likely see the small group huddled around the card table with the sound of dominoes being shuffled echoing in the vacant space. Sometimes, if the game was intense, you might have to wait till Mick played his hand before he’d get you your candy bar. Again, it would not be unusual for one of the old-timers to call out your name and say a few words to you, even if you were just a kid.

Audrey always said Mick was a “piddler,” by which she meant he didn’t do big jobs, just piddled with the little stuff. We kids didn’t see it that way. The man who sold us candy bars was doing important stuff–at least to our way of thinking. I never knew a child in the community who didn’t think Mick’s was the best place in the world.

As times changed and new ways came, Mick’s business dwindled. People didn’t fill up their cars at his station so much anymore, probably because there weren’t all that many people left in our small community. Many had moved to the city where you pumped your own gas into your car and where the candy counter wasn’t two small shelves behind glass doors, but a long grocery aisle with multiple shelves. Then there was some fuss about his storage tanks not being buried deep enough in the ground. Mick kept his place open, but there were fewer tires to change and less tanks to fill. It became mostly a place for old-timers to congregate and to remember old times. After a while, their chairs emptied out as they died off one by one.

On February 17, 1990, Mick turned off the lights and locked the doors. He tried to find someone interested in buying his place, but no one thought it was a profitable enough business. Fewer cars passed by on Highway 267 in front of Mick’s and the few that did were on their way to a bigger place. It was a sad day for the kids of the community. Now they had to go seven miles down the road to get a candy bar. One of my sisters wanted to turn the floor space into an eating place with the catchy name “The Filling Station.” But that didn’t happen either. Mick held an auction to sell off the stuff inside the building. The old candy counter and the coke case were sold along with old tires and old tool sets.

Mick spent most of his remaining years on his front porch. He’d sit on a swing looking out and about, always interested in what was going on in the community. Often enough, Audrey would sit outside with him. They didn’t have any air-conditioners in the house, so being outside made sense, especially in the summer months. You’d see him pick up pecans underneath his trees in the Fall. He moved with slower steps and stooped some as he walked.

Late in the evenings, Mick would shuffle to his old red 1961 Chevy pick-up truck, get behind the wheel, and drive slowly through the community, looking for familiar faces, still remembering all those names, and wondering where all the years and people had gone. Before he bought that used pick-up truck from a farmer down the road, he drove around town for many years in a 1939 Chevy pick-up. It still ran after all that time. The man and the vehicle were almost one.

Mick died in 2001. He was 82 years old. He drew a good-sized crowd to the church because everybody remembered the friendly man who ran the filling station for years and who had sold candy and cokes to the children with a nickel or a dime clutched in their hands. He was remembered as a good man, which is about as good as it gets for any man.

Mick’s now is used to store old cars. A man bought the empty place to house his classic cars. Once in a while, you’ll find the door opened as he pulls out one of his old cars to take a drive down the road. That open door brings back a lot of childhood memories. I just wish I could walk in Mick’s one more time to buy a Zero candy bar. It would taste so good. And it sure would be nice to see those old men again playing “Shoot the Moon” like they did in the good old days.

— Jeremy Myers