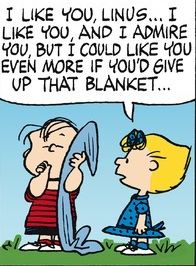

Like Linus, I believe in a blankie. Although I don’t carry mine around continuously as we see that wise-beyond-his-years “Peanuts” character does, still I have an emotional attachment to blankets that probably Linus alone can understand. “Happiness,” Linus once philosophized, “is a warm blanket.” Only the most heartless human being would argue with that belief. Or somebody like Sally, who was quick to tell Linus, “I like you, Linus, I like you, and I admire you, but I could like you even more if you’d give up that blanket.” Thank God he was smart enough to keep the blanket.

When I was a small boy, I watched my grandmother hand-stitch quilts. The key word is “hand.” Because she used the fingers on her hands to do all the work, not a sewing machine on a table top. A couple of times a year, my grandmother would have me help her get her quilting frame off the rafters in her garage. These long wooden posts–four of them–were covered in what I would call pillow material, the blue and white material pillows were made from in years past. We’d bring the long poles into Grandma’s living room–which was the only room with enough space to set up the four frames. She’d bring in high chairs from the snack bar in her kitchen to hold up the four corners of the frame. Then she’d begin the careful process of stretching the bottom layer of whole cloth onto the frame. Then the batting was layered over that cloth. Last the patchwork top would be placed onto the other two layers, forming a sandwich of materials.

“Patchwork” is the right word here because Grandma used real patches, or old pieces of material from her “patch drawer” that she would sew together for the top layer. I don’t recall Grandma being concerned about making a fancy design out of the patches. She was more utilitarian-minded. Four metal clamps held the “stretch frame” together. Then Grandma would begin the tedious work of stitching the three layers together. Thimble on finger, she would push the threaded needle in and out of the layers, securing the batting. Thousands and thousands of times. Thousands and thousands of stitches. Her fingers, stiff and sore, steadily stayed with the sewing until the quilt was done.

As I recall, I had two jobs, which seemed important to a five-year-old boy. The first job was helping my grandmother thread the needle. Already in her 70’s at this point, her eyes weren’t what they used to be and the eye of the needle was too minuscule for her to find with her septuagenarian eyes. She would lick the end of the thread for me–saliva on the frayed end of the thread definitely made the job easier–and then I would pass it through the eye of the needle. As a result, I’ve always found special meaning in the Biblical warning from Jesus, “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 19.24). I know what he meant. The second job I held in the process was to help my grandmother regularly roll up the portion of the quilt she had sewed so that she could have close access to the next portion. Rolling up the quilt onto the frame was easier if there were two hands on each end. I felt very important.

I know there are fancy stitches nowadays and there probably were fancy stitches back then. I doubt my grandmother went for the fancy stuff. Again, she was practical to a fault. She had made quilts all her life long for her twelve children as they grew up. In a day before central heating, heavy quilts were the only means of warmth on cold winter nights. My grandfather didn’t believe in keeping a fire going in the fireplace because of a fear of fire engulfing the house. He also was a practical person. So, the two story farmhouse would get very cold on long winter nights. Or so my mom told me on many occasions.

Grandma was fond of feather ticks, which is a quicker way of making a quilt and a warmer answer to the cold. With these feather ticks, she used string (strategically placed, I assume) to sew through the three layers and knotted the string on the top side. Hence, the name “tied quilts.” Also, thicker material was used for the top and bottom. My grandmother made me a tick one winter, substituting cotton for feathers. I still have it, although I don’t use it because of its fragile state. It is a cherished item from my childhood, as beloved as Linus’ blanket.

Another thing I remember well were the occasions when my grandmother would go to the local church hall to meet with other women (all old, it seemed) to spend the day sewing a quilt. Honestly, I was bored to death. I wandered the back rooms of the hall, trying to find something that would interest me as the women sewed and talked, which I came to see were two equal functions of these “sewing bees” — quilting and visiting. I had no interest in their conversations–apparently so–since I don’t recall anything they said. I do recall that the women made for a happy group and the mood always was light. I think of the sociologist Robert Putnam’s book, “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community”, and I have to believe it easily could have been called “Sewing Alone.” It is a rarity today to find quilting bees or quilting clubs. Some exist, but–like honey bees–they’re on their way out.

In later years, my college years particularly, I received other quilts from women who still knew the skill and who gave me a quilt as a gift. Having watched my grandmother hand-stitch her quilts, I knew that these gifts were special. Every stitch was a moment taken from that person’s life and given to me as a gift. What I saw when I looked at the quilt was not the artistry or the design–although often both were clear–but the investment of time that had gone into that gift. It is an incalculable amount of time required to hand-stitch a quilt and I felt both honored and humbled. Once, a woman on her deathbed told me to go to her closet where she had several quilts she had hand-stitched. She told me to pick out the one that I liked the most. It was mine to keep. I have kept it for these many years since her death. I look at the quilt and I hold in my hands irretrievable hours of her life that she once gave to me.

Much later in life, I also was gifted with a quilt from a church group that met every Thursday to hand-sew a quilt for the annual church raffle. One year they doubled up the work and gave me (since clearly I wasn’t lucky enough to win the raffle) a beautiful quilt that they specially designed to coordinate with the colors in my bedroom. It also is a sacred piece of cloth, as holy to me as any relic made from a midget bit of material worn on a saint’s back. These quilts have taught me a quintessential truth of life–when someone gives you a gift of their time, see it as sacred, for there is nothing in this world more valuable than time. It is a limited commodity and, once spent, it is gone forever. The gift of time is a gift of love.

Unlike Linus, I now have more than one blanket that will never leave my side. Some I use. Others I do not use anymore because of their age. But either way, I will not throw them away. It won’t happen in my lifetime. They are not blankets to me. They are people’s lives that were shared with me in this special way. Hence, they are sacramental, a sign of a holy presence that entered my life and stays with me still in a tattered quilt.

You will understand, then, why I often think of the divine presence in just such a way. It is a warm blanket that shelters us from the cold of this world, a shield made not of metal, but of downy fabric, a softness that gently wraps around us, always with us. That inimitable Jesuit poet, Gerald Manley Hopkins, long ago offered another image when he wrote, “The Holy Ghost over the bent/World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.” He’s right, of course. But maybe it’s just as right to say the Holy Ghost is a warm blanket that wraps around us when the world becomes too much for us children of God and when all we want is to curl up with our blankie and suck our thumb until the monsters of the night go away.

— Jeremy Myers